The Artists Liberation Front and the Formation of the Sixties

Counterculture

In 1976, San Francisco's underground radio station KSAN-FM broadcast a

marathon 72-hour program of interviews and music looking back at the

Summer of Love, the name that the hippies had given to the events nine

years earlier. The producers called this three-day radio program

"What Was That?", a phrase that evokes bewilderment and

astonishment on the part of the questioner about an unexpected and

unexplained experience. It is also a question that many people found

themselves asking, long even after the Sixties faded. Millions of people

participated in these events, and found their lives fundamentally and

radically changed. Some historians would argue that perspective only comes

with enough time to separate the investigation from momentous upheavals.

Nevertheless, it is for all those who are still asking "What Was

That" that we seek to understand the causes of that fateful,

tumultuous, frantic decade.

In the 1960s, the generation of Americans born in the 1940s, the

"baby boomers," came of age. To the dismay of their parents,

they turned away from traditional middle class values -- career, family

and religion -- and adopted lifestyles in open rebellion toward

established institutions. The ideas and attitudes that inspired these new

lifestyles became the soil out of which grew an American counterculture.

The outward aspects of this counterculture contrasted sharply with the

staid fashions of the previous decade. Suddenly, young people were

dressing in strange and exotic ways, adopting bright clothes, faded jeans,

denim shirts, and long hair for the men. Large gatherings of young people

became the decade's watermarks- the be-ins, rock concerts, civil-rights

demonstrations, peace marches, and sit-ins. "Drugs, Sex & Rock 'n

roll" -- this became the decade's anthem.

The inner aspects, the ideas of the counterculture, were harder to

pinpoint: the urge to personal freedom, creativity, direct action to take

control over one's life, reaction against mediocrity and conformity, the

exploration of inner spiritual realms. The older generation mostly saw

only the outward aspects of the counterculture; they could not comprehend

why their children were behaving in bizarre and frightening ways. The

younger generation responded with an innate, intuitive understanding of

the counterculture - while largely unaware of the genesis of these new

ideas.

The Sixties counterculture did not materialize from thin air. It grew

out of a tradition that appears throughout American and Western history,

challenging the basic assumptions of Western culture. We can trace that

tradition through avant-garde arts movements on the one hand, and through

radical political groups on the other. Rarely do such movements combine a

radical political perspective with the avant-garde, bohemian lifestyle.

The fusing of these two approaches was an important development in the

evolution of the Sixties' counterculture. Where did this transformation

take place? That hotbed of the radical, offbeat and subversive - the City

of San Francisco.

The San Francisco Bay Area had provided a fertile breeding ground where

such movements flourished, and where many threads that shaped the Sixties

counterculture first came together. This is a history of ideas that

evolved and combined and synthesized and continued evolving to become the

essential ingredients that were right for the time, to which thousands of

people, mostly young, responded innately. They took up the call, dropping

out of schools, jobs, the military. Like some Pied Piper's army, they

heard a distant call, and disappeared into a magic mountain in the clouds.

This history will attempt to delineate the evolution of ideas that

produced this siren call.

In 1966 a group of San Francisco artists formed an organization for

mutual support and direct action against the arts establishment. They

called themselves the Artists Liberation Front, a name that reflected

their opposition to the United States involvement in the war in South

Vietnam, where the Communist insurgents called themselves the National

Liberation Front. Rarely do artists collaborate; even more rarely do they

collaborate with a political purpose. This synthesis produced far-reaching

effects for the growing counterculture.

We can trace the tradition of avant garde, bohemian arts in the Bay

Area back to Gold Rush days; more directly, a signal impulse happened in

October, 1955, at a poetry reading in San Francisco at the Six Gallery.

Allen Ginsberg read a new poem, now-famous, "Howl." This event

signaled the beginning of a new movement, the San Francisco Poetry

Renaissance. As Tuli Kupferburg put it, "Beat poetry threw art back

into the eyes, the ears, the faces, the bodies of the people. It took type

off the page and once again reading out loud to live audiences started in

coffee shops, later expanding to college campuses, churches, parks,

etc." [note 1]

The North Beach neighborhood, which itself is the traditional home for

two of San Francisco's ethnic minorities (the Chinese and Italians),

became the center of a thriving subculture in the late 1950s. When the

world became aware of the "Beat Generation" [note ?] [a term

Jack Kerouac invented and John Clellon Holmes popularized, from which the

local San Francisco legend and writer Herb Caen coined

"beatnik."], poetry was but one of many arts thriving in the

neighborhood. Painters, sculptors, writers, photographers, dancers,

musicians, film-makers, printers, and poets made North Beach their haven.

Artists shared their lives and work in close proximity.

Inevitably, as the world took notice of this special and unique

neighborhood, the hucksters and hustlers moved in. North Beach soon gained

another reputation as the birthplace of the "topless bar." An

immediate influx of tourist traffic flooded the once-quiet neighborhood,

and the police suddenly took an interest in the poetry-loving,

pot-smoking, bearded and free-swinging denizens of the area. The natural

reaction of the beatniks was "to split the scene," and many

artists moved out of North Beach to other neighborhoods. One such area,

known as the Haight-Ashbury, bordered San Francisco's gem of civic pride,

Golden Gate Park.

At this time (mid-to-late 50s), a new political consciousness was also

developing, and the New Left formed out of the ashes of the Old Left. The

communist scares and witch-hunts which dominated American political life

after World War II had decimated the Old Left. This period culminated in

1953 with the executions of leftists Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, the only

civilians executed in the United States for espionage.

Like the counter-culture, there was an impulse event that signaled the

formation of a new political movement in America. The inspiration for the

rebirth of the American Left moved "from black to white." [note

2] When, in 1955, the black seamstress Rosa Parks refused to take a

seat in the back of a Montgomery, Alabama bus, her arrest led to the

Montgomery Bus Boycott and the beginning of the Civil Rights Movement.

Martin Luther King, Jr. set the the example of nonviolent civil

disobedience campaigns which encouraged young progressives who were too

young to remember the dark days of the early 50s. The first major

demonstration of this New Left occurred in San Francisco in 1960.

The House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC) had been one of

the main sources of terror that silenced the American Left after World War

II. When the Committee came to San Francisco in May, 1960, for a series of

three meetings, a group of students and teachers from the University of

California at Berkeley, across the Bay from San Francisco, and from the

State College in the City, demonstrated against the hearings. On the

second day, the San Francisco police decided to clear the main rotunda of

City Hall, where the Committee was meeting in the Board of Supervisors'

chambers. Using fire hoses and batons, the police beat the demonstrators

down the main marble staircase. Several people were hospitalized. The next

day, the demonstrators came back thousands strong. They held a silent

vigil and picket outside City Hall, where they completely encircled the

Neo-Classical seat of government. It was a non-violent response; the

demonstration remained peaceful all day. In the eyes of the organizers, it

was a victory -- the first victory for a new movement of the Left in

America. Over the next decade, and beyond, Berkeley would remain at the

forefront of radical student politics. After that demonstration, the power

of HUAC to intimidate and destroy people for their political beliefs

diminished.

The San Francisco Mime Troupe emerged in 1959 as a unique blend of

these diverse movements: the avant garde and the radical left. Ronnie

Davis, the founder and director, had studied classical mime in Paris under

Etienne Decroux. The Mime Troupe evolved over the next few years into a

group "in the service of political ideas. " [note

3] They re-invented commedia dell'arte, a sixteenth-century Italian

theater form which was performed in the streets. Commedia featured stock

characters wearing easily identifiable masks.

The Mime Troupe performances shocked audiences with nudity and language

unheard on other stages in the early 60s. Their intention was to break

down the distinction between public and private life. They chose subjects

that were taboo at the time. For example, here is a description of the

Minstrel Show by Peter Coyote, a Troupe actor at the time. "Three

black guys, three white guys, in black face, wigs, tuxedos, gloves."

(The audience couldn't distinguish the black performers from the white

performers.) "Doing what began as an old-time minstrel show and what

ended up just excoriating bullshit on both sides of the color line.

Breaking into skits and dangerous and dirty and scary and people were just

liberated." [note 4]

The Mime Troupe, with the idea of "making public what is

private," took their performances outdoors, outside the walls of

traditional theater. Their first season in the city's parks took place in

1962, with two performances. During the next two years, they lobbied the

Parks Commission for more engagements. Finally, in 1965, the Commission

granted the Troupe's request for 48 dates to perform "Il Candelaio,"

by far the most controversial of their previous productions. After the

third performance, the Commission revoked the Troupe's permit on the

grounds of obscenity. The Troupe ignored the order, and staged the

scheduled performance on August 7, 1965, in Lafayette Park. The police

showed up and stopped the show, arresting Director Davis and two

performers. A lengthy court battle ensued; to raise money for the defense

fund, the sharp business manager of the Mime Troupe staged a benefit at

the Troupe's warehouse studio in the South of Market district.

The show featured poets, performers, and several local rock bands that

were getting started in the Bay Area. Two weeks earlier, some of these

bands had played at the Longshoreman's Hall at an event that became a

milestone for rock concerts, which had been strictly sit-down affairs up

to then. The producers of this first rock dance concert called themselves

The Family Dog. They saw the need to create a place where young people

could get out of their seats and actually dance to the new electric music

that was being played in folk music clubs of the Bay Area. A musical

breakthrough was taking place. It brought the poetic lyrics of folk music

together with electric rock and roll. When The Family Dog held that first

rock dance concert on October 16, 1965, they added a new element to the

mixture -- the idea of a rock concert where the audience participated

actively in creating the event. This new form would have a profound effect

on the emerging community.

The Mime Troupe benefit took place two weeks later. The Troupe's

business manager invited several of the new music groups to perform.

[note: research groups here] No one foresaw the huge crowds they would

attract. Lines of wildly, colorfully dressed young people stood outside

waiting hours to gain admission. The Fire Department showed up and issued

a citation for overcrowding. Thrilled by their success, the Mime Troupe

located another, larger building for a second benefit one month later, on

December 10, at a dance ballroom on Geary Boulevard, the Fillmore

Auditorium. This was the first of what would number thousands of rock and

roll dance concerts at the Fillmore. It launched the career of Bill

Graham, who left his position as the Mime Troupe's business manager to

become a rock and roll dance promoter.

Suddenly thousands of young people were dancing to this electric music

in events that became rites of passage for a new community. The early

months of 1966 saw an explosion of dance concerts that had the effect of

artistic happenings. They combined multi-media lightshows with the

high-energy music and the outrageous costumed dress of the people who came

to dance. Barbara Wohl, a member of the Mime Troupe, described this

period: "Everybody was dancing ... the world had a need to dance and

everybody was a participant in it. You danced without clutching. Everyone

was independent in their dancing, yet everybody danced together. [There]

was this need to dance or being a participant instead of ... sitting there

watching the band ... it was something other than a performance. [Later]

it became a performance. It was just this little instant of time when the

dancer was equal to the musician on the stage and there was no difference

between the performer and the performed upon."[note

5]

The intensity of feeling and community was high. At this moment the

Artists Liberation Front (ALF) was born. One of the member-directors of

the Mime Troupe said, "There was a generally revolutionary ambiance

in the Sixties ... we felt like we were artists and wanted to participate

in the on-going political, revolutionary thing that was going on as

artists, and we were looking for a form." [note 6]

The opportunity presented itself that spring. Mayor Shelley announced

the creation of a new committee to study the arts in San Francisco. The

Arts Resources Development Committee consisted of twenty-six prominent

business people and civic leaders. The Mime Troupe, outraged that the

mayor had not appointed any working artists, crashed the committee's first

luncheon meeting on May 2, 1966 at the Crown Zellerbach Building. The

Troupe "dressed in a variety of costumes from minstrel to

commedia." [note 7] The San Francisco Chronicle

reported that they "were at the meeting to express concern that few

artists were represented." [note 8] The

Director of the Troupe, Ronnie Davis, read a manifesto to the dignitaries.

Then, Harold Zellerbach, the newly appointed chairman of the committee

(and president of the Arts Commission) asked the Mime Troupe to leave the

building.

Two days later, the Chief Administrative Officer (CAO) of San Francisco

announced the awards from the Hotel Tax Publicity and Advertising Fund

(known simply as the Hotel Tax Fund.) This is the tax the City collects on

each hotel occupancy and distributes to arts groups to enhance the

cultural landscape, not the least to benefit the tourist industry. The

Mime Troupe had received $1000 awards in each of the two previous years.

But this year, the CAO cut off the Troupe "without a dime." [note

9]

Ronnie Davis called an open meeting of artists the next week at their

studio. The Mime Troupe press release said they intended to "organize

a program for the cultural development of the area." [note

10] Willie Brown, the San Francisco state assemblyman, chaired the

meetings. Barbara Wohl described the group that formed: "Everybody

yelled at everybody. There were never more anarchists in the same room at

the same time. Artists are a hellish lot to get together." [note

11] Ralph Gleason, the sympathetic San Francisco Chronicle jazz

columnist, wrote that the meeting "may turn out to be one of the most

important events in San Francisco's cultural history." [note

12]

The sentiment at the meetings was strongly against a new large cultural

center, which Harold Zellerbach was advocating. Instead, the artists

wanted "small numerous neighborhood centers to bring art to the

people." [note 13] Peter Berg, a Troupe actor

and writer, and member of the steering committee, coined the term "ArtOfficial"

to describe the mentality that the artists were fighting. Davis himself

referred to the "Edifice Complex" of Zellerbach and others who

wanted to construct large municipal facilities as their contribution to

the arts.

The Artists Liberation Front became a vehicle for working artists

outside the official arts establishment to "band together for mutual

support." [note 14] Out of the meetings that

took place at the Mime Troupe's loft came the idea to produce an

underground arts festival in the City's neighborhoods that fall. Following

the lead of the Appeal Benefits the Mime Troupe had initiated, ALF put on

a benefit at the Fillmore Auditorium, July 17, 1966. Allen Ginsberg read

his new poem, "Wichita Vortex Sutra," and the evening turned

into "a Mardi Gras, a masked ball, with people in costumes, painted

with designs, carrying plasticene banners through the audience while

multi-colored liquid light projections played around them," as Ralph

Gleason described it in his Chronicle column [note 15].

The idea of the festival emerged at a Golden Gate Park press conference

a few days later. "We want to bring theater, painting, music to the

people -- especially people in underprivileged neighborhoods." The

Mime Troupe offered their services free to the public, suggesting free

mural painting, poetry, and theater. [note 16]

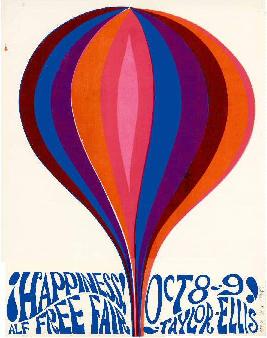

In October, the Artists Liberation Front produced a series of fairs on

four weekends in four different ethnic, low-income neighborhoods. They

were called Free Fairs. For the first time artists had gotten together,

not to sell their art but to invite people to participate in the creative

process. The artists set up kiosks with large rolls of paper and painting

supplies. Kids (of all ages) could make their own art, while bands came to

play. This was the first time the new rock bands played outdoors, in the

streets. [note 17]

The ideas behind the Free Fairs and the Artists Liberation Front are

significant. They represented the first stirrings of the neighborhood arts

movement. The influence on the San Francisco counterculture then emerging

was profound. The free fairs became the first joyous communal

celebrations, one of the most important symbols of the Sixties'

counterculture. The Free Fairs inspired the Love Pageant Rally in October,

1966, which itself was the inspiration for the Human Be-In, in January,

1967. The Be-In itself became the model for similar gatherings worldwide;

the most famous occurred two years later in New York at a farm in upstate

New York, at Woodstock.Barbara Wohl was one of three people responsible

for organizing the Free Fairs. In an interview, she told me what the

Artists Liberation Front meant to her: "It was a extension, for the

most part, of the very kind of loving tender attitude that people had

toward each other then. I haven't seen it since. It was just that short

bubble of time. If you weren't there, you don't even believe it happened

... I didn't articulate it to myself at the time, but what the point of

the fairs was, was not to have artists displaying their works, finished

products, but to have the supplies there so people could make their own

art. ... That was the basic idea of the fairs. It is not someone coming to

observe his picture, but where whoever happened to walk up and see the

paints could become the artist and do his thing, make his own art, be a

participant. This was meant to be, and is, a very political thing. It was

the beginning of this burgeoning toward not passively allowing the

government to go on with the war. ... This erasing of the difference

between the performer and the performed upon was the real nitty gritty of

that, the politics of the whole thing." [note 18]

Through Barbara's words, we can glimpse that brief instant in 1966 when

various threads -- the Beat poetry movement, the Civil Rights movement,

the reborn Left, folk music, and the recent psychedelic dances -- came

together in a new synthesis. The resultant flowering would reverberate

through the counterculture over the next twenty years, and more.

Notes:

1. Tuli Kupferberg, "Roots; Bringing It All

Back Home. The Beat Generation Looks Around," Crawdaddy,

February 20, 1972, p. 36.

2. Michael Rossman, interviw with author,

September 8, 1980, San Francisco.

3. Peter Coyote, interview with author, October

28, 1980, San Francisco.

4. Ibid.

5. Barbara Wohl, interview with author, October

29, 1980, San Francisco.

6. Coyote interview.

7. R. G. Davis, The San Francisco Mime Troupe:

The First Ten Years, Ramparts Press, Palo Alto, CA, 1975, p. 204.

8. "Art Resources Unit Meets," San

Francisco Chronicle, May 3, 1966, p. 48.

9. Mel Wax, "Hotel Tax Divvied Up For

Culture," San Francisco Chronicle, May 5, 1966, p.1.

10. "Artists Meet To Organize," San

Francisco Chronicle, May 9, 1966, p. 51.

11. Wohl interview.

12. Ralph J. Gleason, "Several Sides of the

Cultural Coin," San Francisco Chronicle, May 16, 1966. p. 51.

13. "A Poor Man's Art Commission With

Artists!" Barb, May 13, 1966, p. 1.

14. Peter Berg, interview with author, September

12, 1980, San Francisco.

15. Ralph J. Gleason, "An Old Joint That's

Really Jumpin'," San Francisco Chronicle, July 20, 1966, p.

39.

16. "Artistic Freedom Cry," San

Francisco Chronicle, July 21, 1966, p. 2, and "Artists' Plans for

Liberation," San Francisco Examiner, July 21, 1966, p. 13.

17. Numerous articles appeared in the local

establishment and underground press describing the neighborhood fairs.

See, for example, "It's All Happening," San Francisco

Chronicle, October 10, 1966. p. 10.

18. Wohl interview.

[By Eric Noble, Last text revision: 7 Dec 1996.] |

|