Staging the Revolution: Guerrilla Theater as a

Countercultural Practice, 1965-1968

By Michael William Doyle

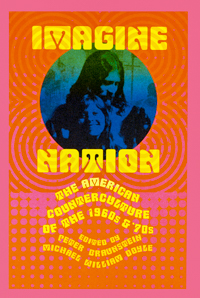

[First published in Imagine Nation: The American Counterculture of the 1960s

and '70s, New York: Routledge, 2002]

<<==>>

Michael Doyle was one of the first historians to delve into

the Diggers with the passion of an amateur in the true sense of the word,

and the scholarship of a professional. Michael visited these Archives on

many occasions starting in the 1980s and proffered his wholehearted

encouragement to this sometimes lonely project. As he developed his skills

and his body of research notes, I began to publish on the Web some of the

primary materials that Michael and other students of Digger history had

used. It became clear that at some point Michael would publish his work,

and so I have waited for this day to be able to present the results of his

efforts. Here then is an essential article about the importance of

Guerrilla Theater in the evolution of the Digger impulse by one of the foremost

historians of the Counterculture. Thank you, Michael.

Note: R.G. Davis wrote an article which introduced the term "Guerrilla

Theatre" and which was published in the Tulane Drama Review in 1966. There

is a separate page in the Digger

Archives which reproduces that original publication.—Ed.

<<==>>

One sunny afternoon in August 1965, R.G. Davis, founder of the

San Francisco Mime Troupe [SFMT], staged a spectacle of politics and art

in a public park. On this day, their fourth summer of presenting free commedia

dell'arte performances throughout the Bay area, the Mime Troupe was

going ahead with plans to perform their latest play, Giordano Bruno's Il

Candelaio, in Lafayette Park in defiance of the San Francisco Park

and Recreation Commission. Two days earlier Commission members declared

the premier show to be "obscene, indecent, and offensive" due to

its "suggestive ... words and gestures," and therefore had

revoked the Mime Troupe's permit for future park performances. Davis and

the ACLU responded by denouncing what they considered to be a blatant

attempt to censor them and violate their right to free speech. "We'll

see you in the park and we'll see you in court," Davis brazenly

promised.

The controversy was simultaneously a farce about civil

authorities policing public morality and a publicity stunt in one act

crafted out of Davis's principled chutzpa and Bill Graham's promotional

savvy. (Graham, who worked for a heavy equipment manufacturer in his

previous job, had recently been hired as the Mime Troupe's business

manager.) A small crowd of free-speech proponents and curious onlookers

turned out to see the show. When one of the commissioners tried to prevent

the Troupe from erecting its stage, Davis maneuvered in front of the

milling audience and announced: "Ladieeeees and Gentlemen, Il

Troupo di Mimo di San Francisco Presents for your enjoyment this

afternoon ... AN ARREST!!!" And with these words he flung

himself into the upraised arms of the police. "The job of the artist

in politics is to take leaps the politicos never take," Davis

afterward wryly observed.(1)

This brief drama in Lafayette Park was little noted outside the

region, but it helped set a wave in motion that would soon hit the country

like a riptide. The forms of political activism and the content of

avant-garde theater in the United States converged in the mid-1960s.

Artists, particularly those who worked in the theater, used the stage to

bring au courant controversies and sweeping social

commentaries to the fore of public awareness. Political protesters,

meanwhile, began increasingly to adopt dramatic forms as a means of

expressing their collective dissent from a society they saw as morally

bankrupt, racist, militaristic, and culturally stultifying. Together these

two developments contributed a distinctive sensibility to Sixties'

cultural politics; the interaction of New Left politics and avant-garde

performance fused to produce the nation's first counterculture to be

called by that name.(2) How this came to

pass can be cogently grasped by tracing the evolution of "guerrilla

theater" as a countercultural practice through its three principal

phases.

<<==>>

Guerrilla theater was first articulated in 1965 in a manifesto

fitfully produced by R.G. Davis, founding director (six years earlier) of

the San Francisco Mime Troupe. By exhorting his theatrical ensemble to

become a Marxian cadre, or at very least a catalyst for social change,

Davis committed the Mime Troupe to serve as a Movement vanguard in the

nascent cultural revolution. This was the formula: they would continue to

broaden their audience by performing in new spaces, such as public parks.

Their plays would be nothing if not topical, suffused with radical

content, and enlivened by biting satire and repartee improvised to suit

the occasion. It was to be funded primarily by free will offerings; no

admission fees would be charged. Largely through the Mime Troupe's

efforts, widely disseminated by means of national tours, the staging of

improvisatory, didactic skits in public spaces became a staple of antiwar,

women's liberation, and other social movement protests.(3)

Guerrilla theater grew directly out of Davis's rediscovery of commedia

dell'arte, which he became interested in after studying modern dance

and mime during the 1950s. A sixteenth-century Italian popular theatrical

form, commedia is known for its stock characters in grotesque

masks who improvise much of their dialogue while playing close to type. Commedia

performers customarily make sport of human foibles and universal

complaints while burlesquing the most socially or politically prominent

members of a given community. Reviving this comedic form was a stroke of

genius on Davis's part. It recuperated the carnivalesque—that fecund

bawdiness that Bakhtin delineated in Rabelais—and transposed it to a

modern American setting.(4) Furthermore,

it furnished the Mime Troupe with an earthy, subversive art form that was

tailored for itinerant players who found their audiences in the streets

and marketplaces. Commedia troupes adapted their skits to local

issues, supported themselves by passing the hat and therefore were not

beholden to wealthy benefactors, and were able to quickly disperse and

slip out of town when the magistrates took offense and came calling.

In May 1962, Davis and the company produced their first commedia—The Dowry—in the parks of San Francisco. The signal

importance of this initiative is that it took serious theater out of the

playhouses and resituated it out of doors, where it might again attract a

diversely popular following. There in the parks performers could mount

plays that were fresh and challenging before new audiences who might not

otherwise go to see theater on a regular basis. By so doing the Mime

Troupe may well have been the first artistic company in a generation to

establish or perhaps reclaim the public parks as a performance venue.(5) As such they prepared a site for countercultural

entertainment and festivity that would soon be thronging with outdoor rock

concerts and be-ins, culminating at the end of the decade with Woodstock

and People's Park.

<<==>>

Davis's leftward lurch accelerated in the early 1960s when he met

and became friends with political activists Saul Landau and Nina Serrano.

Before moving to San Francisco in 1961 from Madison, Wisconsin, the

married couple had been instrumental in founding the influential journal Studies

on the Left. Their mutual interests in theater had led to their

involvement in staging the celebrated Anti-Military Balls at the

University of Wisconsin in 1959 and 1960. The highlights of these events

were elaborate, irreverent skits that satirized the contemporary national

political scene from an overtly socialist perspective.(6) Shortly after meeting Ronnie Davis, Serrano and Landau

became his artistic collaborators.(7)

Landau wrote scenarios and lyrics for a couple of plays, while Serrano

co-directed Tartuffe in the commedia style for

performance in the parks. Through them Davis was introduced to Robert

Scheer who was then working as a clerk in Lawrence Ferlinghetti's City

Lights Book Shop. Davis's political perspective was thoroughly radicalized

through his association with these three individuals.(8)

By mid-decade the Mime Troupe's commitment to radical theater

culminated in an artistic statement that Davis drafted and read to the

company in May 1965. Christened "Guerrilla Theater" by

actor-playwright Peter Berg, who coined the term, Davis's manifesto took

its cue from Che Guevara:

The guerrilla fighter needs full help from the people ....

From the very beginning he has the intention of destroying an unjust

order and therefore an intention ... to replace the old with something

new.

Davis glossed this quotation to contend that the guerrilla cadre

provided a model worth emulating by their theatrical ensemble. Both were

small, highly disciplined groups who were motivated by a righteous cause

to do battle against enormous odds. Journalistic reports by Landau and

Scheer, based on their recent visits to Cuba, may well have brought home

to Davis the powerful example of a revolutionary cadre movement that was

successful in overthrowing a corrupt regime.(9)

Davis's essay indicted American society (but

curiously not the state) for having allowed the political

establishment to vigorously pursue such foreign policy fiascos as the Bay

of Pigs invasion and the Vietnam War. His response to this deplorable

state of affairs was to mobilize the American theater as an instrument of

far reaching social and political change. He proposed that the Mime Troupe

and other like-minded theaters adopt a three-pronged program: to

"teach, direct toward change, [and] be an example of change."

Accomplishing the first objective would require actors to educate

themselves so that they would have something to teach. The second point

openly accepted Brecht's insistence that all art served political

purposes, whether implicitly or explicitly. Davis wanted his fellow

Troupers to declare themselves against "the system" and then

devote themselves to its wholesale transformation. (Just a few weeks

earlier, SDS activist Paul Potter had delivered his much-discussed

"Name That System" speech in Washington, D.C., before the

largest peace demonstration in U.S. history.)(10)

This task was to be accomplished by fulfilling Davis's third

objective: the company should "exemplify change as a group" by

installing "morality at its core" and establishing cooperative

relationships or a coalition with like-minded organizations. Here he

recommended that radical theaters take up Che's example, which for all its

martial trappings was essentially how the traditional commedia

troupes had operated: "[B]ecome equipped to pack up and move quickly

when you're outnumbered. Never engage the enemy head on. Choose your

fighting ground; don't be forced into battle over the wrong issues."(11)

"Guerrilla Theater" was not intended to be a call to

arms, but to a cultural revolt aimed at replacing

discredited American values and norms.(12)

As Davis phrased it, "There is a vision in this theater, and ... it

is to continue ... presenting moral plays and to confront hypocrisy in the

society."(13) What stands out from

Davis's intentions in 1965 is his desire to mobilize a corps of

politicized artists to act as the vanguard of an American cultural

revolution.

And so by mid-decade, as the civil rights, free speech, and

antiwar movements ripened into the Movement, Davis was leading the Mime

Troupe into the van of New Left activism. Together with Landau and

Serrano, they originated the idea for what would become known as the Mime

Troupe's most controversial play from that era: A Minstrel

Show, or Civil Rights in a Cracker Barrel, a production quite unlike

other irreverently political revues of the day. It was to political

theater what Lenny Bruce was to stand-up comedy, an exercise in wringing

the rude truth from the day's news, while straddling the fine line between

mere "bad taste" and the flagrantly lewd. Alternately subtitled Jim

Crow a Go-Go, the show consisted of a series of skits performed by a

racially integrated cast, all but the white, straight-man "Interlocuter"

in blackface. The self-designated "darkies" were costumed in

blue and ivory satin suits, white cotton gloves, and topped off with

short-haired wigs like jet-black scouring pads. Audiences found it

perplexingly difficult to discern the true racial identity of the six

masqued performers, a predicament which rendered the actors' raucous

banter all the more unsettling. Mime Troupe veteran Peter Coyote

attributes the show's critical success to its offering "a rare

cultural epiphany perfectly in synch with the historical moment." The

Minstrel Show had appeared at a time, he surmises, "when the

civil rights movement and the emerging black consciousness fused with a

social upheaval in the nation's youth to make society appear suddenly

permeable and open to both self-investigation and change."(14)

Davis hoped to hone the radical edge of this production by means

of form as well as content. To this end he solicited members of the local

civil rights activist community to audition for parts, conjecturing that

if he could locate several men who possessed both a progressive political

sensibility and a measure of native talent, they would be able to polish

their acting skills in rehearsal. Experience in civil rights advocacy, he

maintained, would be indispensable to carrying out the task Davis and his

collaborators had set out for the show: exposing the deep-seated nature of

prejudice in contemporary society. The American minstrel show format would

be redeployed in a way that subverted the racist stereotypes that had

permeated the traditional traveling mode of entertainment. It would

parallel what the Mime Troupe had done with commedia—adapt a popular theatrical form to explore a series of wide-ranging,

contentious topics, in this case selected from more than a century of

American racial discourse.

No subject was to be considered off-limits: interracial sexual

relationships, myths of African-American male potency, and class conflicts

within the black community were each dramatized and critiqued. The

ghettoization of the past as represented by "Nego History Month"

[sic] was lampooned without mercy (Crispus Attacks, the first African

American to die in the Revolutionary War, gets shot by Redcoats while

pushing a broom). In another skit, the irony of black soldiers killing

"yellow men" in Vietnam by orders of a white imperialist command is

put across with the austere didacticism of Bertolt Brecht. Institutional

racism, naive integrationism, police brutality, craven Uncle Toms,

supercilious white liberals, and arrogant black militants—all received

their jocund due. In order to ensure that the play's satirical barbs hit

their many intended targets, staff members of the local SNCC and CORE

organizations were invited along with the cast to critique the play while

it was still in development.(15)

The Minstrel Show attracted national attention for the Mime

Troupe when they produced it on their first cross-country tour in 1966.

Comedian and civil rights activist Dick Gregory sponsored its performance

at Town Hall in New York, which garnered an enthusiastic review from no

less than the New York Times.(16)

Around this same time Davis sought other ways to strengthen ties

between the avant-garde and the Bay area radical movement. The Mime Troupe

made their rented studio in the Mission District available for use by the

New School, a project coordinated by Landau and Paul Jacobs as the first

of the "free universities" to spring up in the wake of the FSM.

Davis was one of its board members and he co-taught a course on art and

politics during its summer session in 1964.(17) When the Troupe relocated to a downtown loft on Howard

Street the next summer, they furnished SDS with an office. Still later,

they shared their facilities with San Francisco Newsreel, a radical

filmmaking collective. This mingling of artists and political activists

which the Mime Troupe facilitated ensured that culture and politics would

not be as bifurcated in the Bay area as it may have been elsewhere.

<<==>>

Davis clarified and extended his guerrilla theater idea twice

more in essays published before the decade's end. The next installment,

written in late 1967, embraced an eclectic Marxism glimpsed through the

prism of the Summer of Love. In it he located the source of American ills

not in corporate liberalism, as Studies on the Left and

SDS had, but in the very system of private property. To counteract this

"disease" of creeping materialism he advocated "dropping

out" of bourgeois society and devising in its stead an alternative

"life-style that replaces most, if not all, middle-class capitalistic

assumptions." Davis was sparse on the details—as with his plays,

he preferred the dramatic gesture to the searching soliloquy. He did

explain that this lifestyle must itself constitute a "moral

force" that would work within one's community of origin (reckoned not

by geography, necessarily, but by one's class, racial and/or ethnic

background). Its purpose was to criticize "prevailing conditions ...

expressing what you (as a community) all know but no one is saying ...

truth that may be shocking and honesty that is vulgar to the

aesthete."(18) Speaking truth to

power, just as Quaker activists had been urging, would before long become

standard practice among those operating within the framework of identity

politics.

The serious purpose behind Davis's proposal was elaborated in a

third essay he published the next year. There he noted that guerrilla

theater as he had formulated it in 1965 had subsequently "become a

catch-all for non-professional theater groups," because of a

fundamental misinterpretation by these would-be imitators. He now took

care to distinguish his original idea, "which describe[d] activity on

the cultural front in the USA" [emphasis mine], from

that of "armed revolutionary action." Despite obvious

differences, he argued, the two did have this much in common: "The

cultural revolutionary, just as the armed guerrilla, must want and be

capable of taking power." Power will be seized, he averred, by

radicals who operate simultaneously on three fronts: ideological (e.g.,

performing for audiences of the unconverted, undermining their

"bourgeois mentality"), economically (ending exploitation and

consumerism by organizing not-for-profit alternative cultural

institutions), and physically (here, while his meaning was unspecified, he

encouraged disciplined collective action aimed at destroying both

individualism and elitism.)

The article was to be his longest think piece on the subject, yet

it is vexingly vague about what it would mean for cultural revolutionaries

to actually seize power. One must infer from certain textual clues that

American "corporate liberalism," and "imperialism"—its dream of global domination—(he finally did employ these terms)

would both be smashed, and that some sort of socialism would be adopted in

the post-revolutionary society. But all we can be sure about Davis's

intentions at this point is that he recognized the politicized artist as

the vanguard of the cultural revolution. "This is our society,"

he intoned, uttering the last lines of the Mime Troupe's recent antiwar

play L' Amant Miltaire; "if we don't like it[,] it's

our duty to change it; if we can't change it, we must destroy it."

Perhaps then, perhaps only then a vision of what exactly to replace it

with would emerge. Davis's nihilistic bombast forecast the direction that

at least some members of the ultra left would head in the months and years

ahead.(19)

<<==>>

Guerrilla theater's second phase began in fall 1966 when a number

of Mime Troupe members, some twenty in all, broke away from the company to

found a free-wheeling anarchist collective they called the Diggers.(20) Just as

Ronnie Davis had turned to the past for inspiration

in reviving popular theatrical forms such as commedia dell'arte

and the minstrel show, so too did the Diggers. Their name derived from a

seventeenth-century group of English millenarians who, in the aftermath of

the English Civil War, quixotically resisted the enclosure of the commons.

Envisioning the establishment of a cooperative commonwealth, these

displaced peasants and artisans practiced what they preached, sharing

their food and possessions among themselves as well as with those who were

even more destitute. "And let the common people, that say the earth

is ours, not mine," Gerrard Winstanley, their most

eloquent spokesman, beseeched all who would listen, "let them labor

together, and eat bread together upon the commons, mountains, and

hills." But when the Diggers dared to dig up, fertilize, and plant

their crops on the common of St. George's Hill, a barren heath near

Surrey, they were decisively put down and scattered by the combined forces

of the lords, freeholders, and soldiers from Cromwell's New Model Army.(21)

The Diggers of San Francisco seem not to have made a detailed

study of their English forebears, probably because they were less

interested in them as a model than as an inspiration. What appealed to

them about the earlier group was that it was a movement that had emerged

spontaneously from within the ranks of the oppressed. What the two groups

shared was a vision of the total transformation of social and economic

relations, a dedication to bringing about the New Jerusalem by peaceable

means, a reliance on pamphlets and direct appeals to spread their message,

and perhaps most importantly, a belief that exemplary actions were the key

to realizing their ambitious goals. And like their namesakes, the

Haight-Ashbury Diggers were seeded with inspired writers who produced

tracts filled with prose that was overtly political and verged

occasionally on the ecstatic. Both groups managed to exert a measure of

influence that was disproportionate to their small number; both proved

ultimately to be short-lived.

Most of the founding core of the later Diggers had had no

professional training or even much experience in drama before they joined

the Mime Troupe. Davis announced in his original guerrilla theater essay

that he wanted to work with people from outside of theater. He hoped that

this would bring in fresh perspectives from other disciplines, just as he

himself had done by importing techniques derived from modern dance and

mime.(22) That Davis succeeded in

his object may be seen in the variety of artistic talent represented by

those Mime Troupe members who left to form the Diggers. They included

writers (Berg, Coyote, Grogan, Kent Minault, Billy Murcott), dancers (Judy

Goldhaft, Jane Lapiner), painters, sculptors (Roberto La Morticella),

filmmakers, musicians, printmakers (Karl Rosenberg), among others.(23)

Significantly, by being relatively unschooled in dramatic theory

and technique beyond what they had absorbed in the SFMT, the Diggers felt

no compunction to strictly observe theatrical convention. Instead of

attaining artistic critical success or even in raising the political

consciousness of popular audiences, the Diggers strove to dramatize the

hip counterculture as a "social fact." Utopia—the "good

place" that in Thomas More's coinage is "no place"—would

be played out daily in the Haight.

To this end, the Diggers borrowed from the Mime Troupe the

ensemble form, as well as the aggressive improvisational style, the

itinerant outlaw posture, and the satirical social critique mode of commedia

dell'arte. They also appropriated Davis's dramatic form of guerrilla

theater and gave it a new twist. Where he had taken theater out of its

traditional setting to stage it in the parks, the Diggers took theater

into the streets. In the process they attempted to remove all boundaries

between art and life, between spectator and performer, and between public

and private. The resulting technique, which they referred to as

"life-acting," punned on the dual meaning of the verb "to

act," combining the direct action of anarchism with theatrical role

playing. The Diggers' principal project was to enact 'Free,' a

comprehensive utopian program that would function as an working model of

an alternative society.

For the Diggers the word free was as much an imperative as

it was an adjective. The object was to place it before any noun or gerund

that designated a fundamental need, service, or institution, and then try

to imagine how such a thing might be realized.(24) Thus 'free press' evolved a new connotation from first

amendment guarantee to an "instant news" service that

disseminated free broadsides in the Haight on a daily basis. Free

transportation suggested the obligation to pick up hitchhikers, and for a

time called into existence a small fleet of vans, trucks, and buses that

shuttled people around town and across the Bay to Berkeley. Bill Fritsch

thought up the free bank and stashed a wad of donated cash in his hat from

which to make no-interest "loans." He even kept a ledger to keep

track of where it all went. (25)

The project of 'Free' all started in early October 1966 with free

food dished out in Golden Gate Park every day at 4 P.M. Next it was

manifested in the free store, which parodied capitalism even while

redistributing the cornucopian bounty of that system's surplus. The free

store's first name was the Free Frame of Reference which derived from the

tall yellow picture frame that the Diggers would have people step through

before being served their daily stew and bread. The frame represented what

was possible when people changed their conceptual paradigm for

apprehending reality. As such the Diggers stood squarely on the side of

the hippies in their ongoing philosophical debate with the politicos: if

one wanted to change the world, it was necessary first to change one's

consciousness or point of view.

Added to these various free services were others that gradually

took shape between 1966 and 1968: free housing in communal crash pads and

outlying farms, free legal services, and a free medical clinic. For

entertainment there were occasional free film screenings, and of course

free dance concerts by local bands of growing renown such as the Jefferson

Airplane, Grateful Dead, Big Brother and the Holding Company, and Country

Joe and the Fish. By the winter of 1967-1968, there was even a

Digger-sponsored initiative supported by prominent members of the Bay area

clergy to provide "free churches" by allowing their sanctuaries

to remain open to worshipers around the clock. Taken together, these

institutions, practices, and services comprised what by the end of the

Summer of Love the Diggers were calling the Free City network.

The sources of support for the Free City activities were various.

Labor for Digger projects was furnished almost entirely by volunteers. The

story of the Haight was the sizable number of idle youths who had come to

explore the hippie lifestyle, and it was this population that the Diggers

attempted to mobilize. Demographically those who chose to work with the

Diggers were in their teens and twenties, primarily white, from middle-

and working-class backgrounds, and many were at least partially college

educated. Along with these advantages, they had time on their hands; some

could depend upon financial assistance from their families of origin. Rock

bands and promoters were probably the single largest financial donors

(e.g., the Grateful Dead's communal dwelling housed the Haight-Ashbury

Legal Organization which they funded to provide free legal assistance). In

addition, at least up until the middle of 1967, certain community-minded

dealers of psychedelic drugs made cash contributions. And whether because

of guilt, coercion, or altruism, some members of the Haight Independent

Proprietors association tithed to the Diggers from the profits they

realized on their retail sales (primarily to tourists who had come to gape

at the hippies).

The Diggers would be unimaginable without their having been able

to draw upon the vaunted affluence of a 'post-scarcity' society. Surplus

goods were more easily available during the economic boom of the

mid-1960s, which followed a long period of post-war prosperity.

California's share of defense spending was huge; consequently unemployment

was minimal and more discretionary spending was possible. Ironically, the

Bay area in particular benefitted from being the point of departure and

reentry for troops involved in prosecuting the Vietnam war. Then, too,

there was the money being pumped into the city by Great Society programs,

some of which undoubtedly trickled down to the Diggers.

Other factors which facilitated the Free City network

include the relatively low cost of living in San Francisco at the time;

for example large apartments and storefronts were quite plentiful and

could be leased at reasonable rates.(26)

Communal living helped further reduce expenses for individuals by the

pooling of resources, enabling members to subsist on a meager income.

Finally, the city's Mediterranean climate was relatively mild compared

with much of the rest of the country, thereby keeping expenditures for

heating and cooling to a minimum, as well as negating the need for

extensive seasonal wardrobes. All of these were conducive to incubating

the Diggers' utopian project.

<<==>>

When beneficence and windfalls failed to deliver essential

items, the Diggers hustled; they were not above resorting to theft or

intimidation to obtain food, for instance. The principle of 'Free'

authorized, even valorized "liberating" goods from uncooperative

suppliers for the benefit of the "New Community."(27) It wasn't so much that the Diggers believed the ends

justified the means, as that the means and the ends were for all practical

purposes identical. Those who thought otherwise would be in Rousseauvian

terms forced to be free.(28)

The Diggers understood from the outset that their project

involved 'acting,' but it wasn't exactly theater even by Ronnie Davis's

iconoclastic standards. To their mind, if one strongly objected to

capitalism, then one simply abolished the system of private property along

with the controlling assumptions of a money-based economy. In its place

the Diggers pushed the concept of "everything free," another

notion that combined two commonly understood meanings of the word: costing

nothing and liberated from social conventions. Freedom or liberty, they

maintained, is one of the genetic codes in the American body politic. By

the middle 1960s, in the wake of the Civil Rights movement's legislative

victories, "freedom now" acquired a new, transpolitical/

psychological cast that was conveyed by the term "liberation."

The Diggers' notion of 'Free' drew on this free-floating, cultural

striving for total emancipation. But their particular practice of 'Free'

was also inspired by the Mime Troupe's approach to producing theater in

the parks: free public performances to be covered by free-will donations.

The guerrilla theater of the Diggers was manifested in its most

spectacular form in street theater "events" they staged in

public places at irregular intervals of approximately every few weeks. The

purpose of these avant-garde happenings varied from attacking the creeping

commodification of the counterculture (as in the "Death of Money,

Birth of the Haight" (17 December 1966), to the widely noted and

similarly named "Death of Hippy, Birth of the Free Man" (6

October 1967). Held to ceremonially mark the end of the Summer of Love,

the Death of Hippy event mounted a radical critique of the mass media's

role in framing and defaming the counterculture via sensationalistic news

coverage. Each event was unique. To impart a sense of what one involved,

here is how the "Full Moon Public Celebration" of Halloween 1966

was structured:

On the southwest corner of the intersection of Haight and

Ashbury Streets, the symbolic heart of some in the community were calling

"Psychedelphia," the Diggers set up their 13-foot tall yellow

"Frame of Reference." Two giant puppets, on loan from the Mime

Troupe and resembling Robert Scheer and Berkeley Congressman Jeffrey

Cohelan,(29) performed a

skit entitled "Any Fool on the Street." The puppets were

maneuvered back and forth through the frame, as their puppeteers

improvised an argument in character about which side was 'inside' and

which 'outside.' All the while the eight-foot high puppets encouraged

bystanders to follow their lead and pass through the frame as a way of

"changing their frame of reference." Meanwhile, other Diggers

distributed smaller versions of the Frame made out of yellow-painted laths

six inches square attached to a neck strap. These were meant to be worn—not as talismans for warding off baleful influences—but as reminders

that one's point-of-view (and hence waking consciousness) was mutable.

Effecting changes in objective reality, the Diggers maintained, had to be

preceded by altering people's perspective on the assumed fixity of the

status quo. Renegotiating those underexamined assumptions might well

produce new and more imaginative ways of organizing social relations.

Next, participants were guided in playing a game called

"Intersection," that involved people crossing those streets in a

way which traced as many different kinds of polygons as possible. The

intended effect was to impede vehicular traffic on Haight Street as a way

of deterring the growing stream of tourists who had come to gawk at the

hippies. One problem, however, was that as groups like the Diggers

acquired a reputation for creating spectacles in the Haight, such doings

inevitably attracted curiosity seekers from outside the neighborhood. From

the Diggers' standpoint, anyone was welcome to join in their events, but

mere spectators were actively discouraged. And they and the other hip

residents of the district reserved a special animosity towards the

nonstop, bumper-to-bumper carloads of people who had come to stare at them

through rolled-up windows and locked doors.

Within an hour (at around 6 P.M.) a crowd of some 600 pedestrians

had gathered to partake in the Digger activities. Not long afterward the

police arrived in several squad cars and a paddy wagon to disperse the

crowd. In a priceless moment of unscripted theater of the absurd, police

officers began a series of verbal exchanges with the puppets! A journalist

on hand captured the ensuing dialogue:

Police: "We

warn you that if you don't remove yourselves from the area you'll be

arrested for blocking a public thoroughfare."

Puppet: "Who

is the public?"

Police: "I

couldn't care less; I'll take you in. Now get a move on."

Puppet: "I

declare myself public—I am a public. The streets are public—the

streets are free."

The altercation, it should come as no surprise, resulted in the

arrest of five of the Diggers—Grogan, Berg, La Morticella, Minault, and

Brooks Butcher—along with another member of the crowd who objected to

the police's action by insisting that "These are our streets."

As the arrestees were being driven away, the crowd began chanting

"Frame-up! Frame-up!" to which the arrested men responded from

within the van, "Pub-lic! Pub-lic!" As many as 200 people

remained on the scene afterward in defiance of police orders. They resumed

the Intersection game and, after one of the Diggers set up a phonograph

and started playing music, began to dance in the street. The officers may

well have attributed the night's outlandish public behavior to the effects

of a 'blue moon' on All Hallow's Eve. To the Diggers it was a

demonstration of their power to confound the authorities and stake their

claim on the urban turf.

<<==>>

As the author of the guerrilla theater idea, R.G. Davis was

sharply critical of the Diggers, as he would soon also be of the Yippies.

He rejected what the Diggers were doing as being neither serious nor

effective. Nor to his mind did it qualify as a legitimate type of

political theater. (This he distinguished from merely acting theatrically

in public.) Davis defined himself and the Mime Troupe first and foremost

as theater professionals who were dedicated to the

transformation of society through the practice of their art.(30) For the Diggers' part all theater involved the

willful suspension of disbelief by those who participated in it. Their

play on guerrilla theater attempted to extend that suspension of

disbelief, act out alternatives to bourgeois "consensus reality"

in its liminal space, demonstrate that these alternatives were possible,

and thereby convince others to join them in enacting the Free City into

existence. Stripped to its bare essentials, today's fantasy might well

furnish a description of tomorrow's reality. And in this belief, they

situated themselves squarely in the American utopian tradition.

<<==>>

The third phase of guerrilla theater is exemplified by the

Yippies, who emerged in New York in early 1968 through the efforts of

Jerry Rubin, Abbie Hoffman, Jim Fouratt, and Paul Krassner, among numerous

others. Another loosely bounded collective, they intended their

felicitously named Youth International Party to mobilize a mass

demonstration of antiwar activists, Black Power advocates, and

disaffiliated hippies in Chicago that August at the Democratic Convention.

The Yippies turned guerrilla theater away from a kind of pre-modern

reliance on face-to-face contact with a popular audience, as it was

practiced by the Mime Troupe. But they also moved it away from its more

modern adaptation by the Diggers, who had attempted to obliterate the

distinction between art and life, and between actor and audience. By

contrast, the Yippies' version of guerrilla theater, which Hoffman

designated as "media-freaking," was to commit absurdist,

gratuitous acts that were carefully crafted to obtain maximum publicity.

As Hoffman explained it, "The trick to manipulating the media is to

get them to promote an event before it happens.... In other words, ... get

them to make an advertisement for ... revolution—the same way you would

advertise soap."(31)

In the months prior to the founding of the Yippies, in

fact, throughout 1967, several members of the group had put themselves

forward publicly as the de facto East coast branch of the Diggers. The

Haight-Ashbury Diggers, more than any other group during the past year and

a half had served as the New Yorkers' inspiration.(32) The Diggers had instructed them in the art of

guerrilla theater, had given them a vocabulary for expressing direct

action politics, and had improvised scenarios which the latter group drew

upon in their own efforts to enact the counterculture.

Besides freely adapting scenarios that had been scripted

largely by their Haight-Ashbury counterparts, the New York Diggers

occasionally improvised some novel ones of their own. But for examples of

the former, they began serving free food to hippies in Tompkins Square

Park, organized a "Communications Company" to freely distribute

mimeographed broadsides that were often reprints of the Digger Papers, and

even opened a free store. They borrowed the San Francisco Diggers'

guerrilla theater technique of "milling-in" (i.e., the

"Intersection Game") as it had been improvised on Halloween

night 1966 in response to the vehicular traffic congestion on Haight

Street. On the first Saturday night of August 1967, Jim Fouratt and other

New Yorker Diggers summoned hippies to block traffic on St. Mark's Place

between Second and Third Avenues. Their object was to convince the City to

convert that block, the heart of the Lower East Side's hip community, into

a pedestrian mall. They carried cardboard replicas of traffic signs, so

that in place of the usual protest demands, their placards read

"Stop," "Yield," and "No Parking." Throngs

of hippies laid claim to the street in equally inventive ways, some of

them through the expression of mystical exuberance by chanting and dancing

"the Hare Krishna hora." The police were present in force, but

did nothing to halt the activities because of a prior arrangement between

them and Fouratt. Securing the officers' restraint came with a price,

though. Fouratt had to agree to keep the demonstration brief—no more

than fifteen minutes.(33)

Later that same month the New York Diggers created their

most memorable spectacle that represented a decisive break with the San

Francisco group's practice of guerrilla theater. It was planned and

executed by Hoffman, Fouratt, and several others including Jerry Rubin,

who had just moved to town from Berkeley a few days earlier. The group

arranged for a tour of the New York Stock Exchange under the auspices of

ESSO (the East Side Service Organization, a hip social services agency;

the fact that this acronym was better known as the name of a giant oil

corporation is probably what gained them entre to the NYSE). Once they had

been escorted into the visitors' gallery above the trading pit, they

produced fistfuls of dollar bills and flung them from the balcony onto the

floor below. All bidding stopped as traders impulsively switched from

their usual frantic mode to an atavistic frenzy, scrambling to grab what

they could from the shower of cash. Then they began to berate the Diggers,

perhaps in part because they realized how this interruption had

manipulated them to reveal the fine line between greed and self-interest

that runs through the heart of finance capitalism.(34)

This event was pivotal for the New York Diggers. It

retained elements of borrowing from the Haight-Ashbury group. Fouratt, for

instance, explained their action as signifying "the death of

money." Hoffman, who had registered for the tour under the West coast

Digger alias "George Metesky," set fire to a five dollar bill

afterward outside the Exchange, just as Emmett Grogan had done famously

earlier in the year.(35) But the

New York group also introduced some new elements into the neoteric art of

guerrilla theater. The choice of setting was far from their accustomed

habitat: the very capitol of capital. It was also presented for the

edification of two audiences. The primary one consisted of the traders

themselves, who were unwittingly manipulated into acting in a kind of

latter-day morality play, and a secondary one which was not present.

Hoffman intended to reach the latter audience via the print media by

tipping off reporters to the Diggers' plans in advance. The Haight-Ashbury

Diggers would denounce such a tactic as a mere publicity stunt, not

permissible under the rules of engagement of their version of guerrilla

theater, because it created spectators instead of engaged actors.

Furthermore, the Stock Exchange event was not meant to ritually constitute

a countercultural community in place, nor to extend or defend its

boundaries, as most of the San Francisco Diggers' events were designed to

do. The New Yorkers' action instead, preached to the unconverted about a

cultural revolution that would not stay confined to the psychedelic

ghettos. As the first Digger spectacle to involve both Rubin and Hoffman,

it also indicated the types of activites that Yippie would soon be

undertaking.(36)

<<==>>

During the second week of September the New York Diggers

staged another innovative guerrilla theater event they called "Black

Flower Day" at the Consolidated Edison building on Irving Place. It

began by them placing a wreath of daffodils dyed with black ink on the

ledge above the lobby entrance, and then handing out similarly stained

wreaths to passers-by. They also strung up a large banner on the building

which declared "BREATHING IS BAD FOR YOUR HEALTH." Next they

fanned into the lobby a sizable pile of soot which they had dumped on the

sidewalk, and danced around—one of them clad in a clown suit—throwing soot in the air. As the police arrived, the Diggers hurriedly lit

a couple of smoke bombs and fled the scene. Don McNeill, a Village

Voice journalist who wrote the article on which this account is

based, remarked that "the Digger drama [was] improvised with the idea

that a handful of soot down an executive's neck might be more effective

than a pile of petitions begging for cleaner air."(37) This event furnishes another example of how the New

York Diggers were not merely being derivative of their Haight-Ashbury

counterparts. By focusing attention on the effects of pollution on the

natural and urban environment they skillfully adapted the technique of

guerrilla theater to articulate an ecological critique before it had

become a popular cause.

<<==>>

Around this time, members of the Haight-Ashbury Diggers

began to strenuously object to the use of the name Diggers by the New York

collective. It would seem that they were ideologically disposed to share

everything freely with anyone except their good name. The objection in

this case, however, was directed specifically toward Abbie Hoffman and

Jerry Rubin for cultivating their images as countercultural leaders or

spokesmen. They also took offense at the New Yorkers' penchant for

publicizing their zany activities in the mass media. The San Francisco

group insisted that their East coast namesakes disassociate themselves

from the Digger movement. As a result, by the end of the year the name

"Yippie!" was devised, along with a new organizational framework

for the New York group; it had the virtue of being free of any contested

associations, and also marked a shift in the focus of operations from the

local to the national scene.(38)

By the summer of 1968 this tension between the Diggers and

the Yippies exposed an irreconcilable conflict between two of the most

prominent tendencies within countercultural activism. For the

utopia-tinged vision of the Yippies' Festival of Life had its roots at

least partly in the Free City project of the Diggers. On the other hand,

the "Festival of Blood" (as a Chicago Yippie organizer was to

presciently call it a week before demonstrators clashed violently with

police), was scripted in concert with what I maintain was the Yippies'

deliberate misprisioning of the Diggers' approach to guerrilla theater.

Interestingly, the Yippies' version would resemble in its praxis the more

militant theoretical formulation by R.G. Davis.(39)

The Yippies' proclaimed raison d'etre was

to create a new national organization whose goals were, first, to

politicize members of the hippie counterculture generally; and, second, to

bring them together with other Movement activists and curious uncommitted

young people at a "youth festival" to be held concurrently at

the Chicago Democratic convention in late August 1968. Initially, at least

according to Jerry Rubin's announcement of Yippie plans for the festival

in mid-February 1968, the gathering was to represent a new direction for

the antiwar movement. It was designed to shift activists not from

"protest to resistance" against the state, as the National

Mobilization Against the War in Vietnam had represented its October 1967

march on the Pentagon. In actuality it would mark a turn from protest to a

frontal assault on American culture. The charge, however, would be led by

a most unconventional brigade. Nonviolent hip youths would come to Grant

Park, near the convention center, and recreate their incipient

"alternate life-style" in all its variegated splendor, much as

though they were a living exhibit of Plains Indians on stockaded display

at the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition. An audience of millions would

visit the Yippie "Do-In" with the news media's unwitting

compliance. Television and print journalists from around the world could

be counted on to troll for colorful feature stories to augment the endless

speeches and procedural vote-taking of the four-day political convention.

In February 1968 Rubin wrote his friend Allen Cohen, editor

of the San Francisco Oracle underground newspaper,

that he wanted to recreate the communitas of the Haight-Ashbury's Human

Be-In through what would soon be designated as the Festival of Life:

[O]ur idea is to create a cultural, living alternative

to the Convention. It could be the largest gathering of young people

ever: in the middle of the country at the end of the summer. ... We want

all the rock bands, all the underground papers, all the free spirits,

all the theater groups—all the energies that have contributed to the

new youth culture—all the tribes—to come to Chicago and for six

days we will live together in the park, sharing, learning, free food,

free music, a regeneration of spirit and energy. In a sense, it is like

creating a SF-Berkeley spirit for a brief period in the Midwest ...

thereby breaking people out of their isolation and spreading the

revolution. ... The existence of the Convention at the same time gives

us a stage, a platform, an opportunity to do our own thing, to go beyond

protest into creative cultural alternative.(40)

Rubin elaborated on this notion not long afterward in an

interview in the Chicago Seed:

In Chicago in August, every media [outlet] in the world

is going to be here ..., and we're going to be the news and everything

we do is going to be sent out to living rooms from India to the Soviet

Union to every small town in America. It is a real opportunity to make

clear the two Americas. ... At the same time we're confronting

them, we're offering our alternative and it's not just a narrow,

political alternative, it's an alternative way of life.(41)

The operative term in this statement is

"confronting," for Rubin and Hoffman clearly understood that

their Festival of Life would likely provoke a violent backlash by Mayor

Richard Daley's minions of law and order.(42) And as expected Mayor

Daley relished his role in this

scenario, playing a cat-and-mouse game with the various protest

organizations that attempted to secure permits for holding demonstrations

outside the Convention and for sleeping outdoors in the parks. Ultimately

no permits were granted, thus ensuring a confrontation. To meet this

contingency, Daley coolly marshaled his forces into place—11,500

policemen; 5,600 Illinois National Guardsmen; 1,000 federal agents; plus a

reserve of 7,500 U.S. Army troops stationed at Fort Hood, Texas, who were

specially trained in riot control and could be summoned to Chicago on a

moment's notice should their services be required. The 10,000 or so

protestors who eventually did show up readily grasped their predicament.

When the pitched battles inevitably came, their only recourse was to chant

to the news cameras: "The whole world is watching!" in the vain

hope that the cops would be chastened by this presumed collective gaze and

desist.(43)

By the summer of 1968, then, one can discern the divergence

of two tendencies among cultural radicals on the left. The first is the

Yippie project of organizing a media spectacle ostensibly for the purpose

of promoting the counterculture. The New York-based organizers, however,

had an ulterior motive: to intentionally trigger a violent reaction so as

to, in Rubin's words, "put people through tremendous, radicalizing

changes." Their objective, he added, was to stimulate a "massive

white revolutionary movement which, working in ... cooperation with the

rebellions in the black communities, could seriously disrupt this country,

and thus be an internal catalyst for a breakdown of the American ability

to fight guerrillas overseas."(44)

A second tendency, already fading from the scene by this time,

was represented by the San Francisco Diggers' experiment in fashioning a

communitarian utopia by means of guerrilla theater which performed a new

set of social relations within distinct geographical boundaries. It was

the New West's answer to the City upon a Hill. During their twenty-one

month tenure, the Diggers in effect improvised a play whose plot concerned

how one community could be transformed root and branch into an alternative

to the rest of American society. What the Yippies took from the Digger

version of guerrilla theater was an appreciation of its spectacular

component and its weirdly appealing absurdity; they appreciated as well

its potential value for garnering publicity. These aspects they blended

with the rhetoric of an artistic insurgency as initially formulated by R.G.

Davis.

The Diggers' civil rites were intended symbolically to

constitute a small-scale 'New Community' out of the otherwise anomic mass

of their urban milieu.(45) Where

the Mime Troupe had dramatized their radical politics in the parks, and

the Diggers had enacted theirs in the streets, the Yippies projected a

kind of postmodern critique of and challenge to Lyndon Johnson's Great

Society designed to play on the stages of the mass media. But instead of

galvanizing a groundswell of support for their cause, as they had hoped,

the Yippies' mass mediated countercultural revolt culminated in a bloody

'police riot' in real time, one which ultimately lost in the ratings. To

paraphrase Gil Scott-Heron, the revolution would not be televised.(46)

<<==>>

Notes

1. Harry Johanesen, "Park

Show Canceled; 'Offensive,'" San Francisco Examiner [Exam.]

(5 Aug. 1965) 1, 16; Donald Warman, "Cops Upstage Mimers in The

Park," San Francisco Chronicle [Chron.] (8 Aug.

1965) 1A, 2B; Michael Fallon, "Park Mime Star Arrested; Banned Show

Goes On," Exam. (8 Aug. 1965) 1B; Ralph J. Gleason, "On

the Town" column, "Maybe We're Really in Trouble," Chron.

(9 Aug. 1965) 47. Davis's account is in his memoir, The San Francisco

Mime Troupe: The First Ten Years [The SFMT] (Palo Alto,

Calif.: Ramparts Press, 1975), 65-69. The second quote by Davis is taken

from the transcript of a panel discussion in Radical Theater Festival,

San Francisco State College, September 1968] (San Francisco: San

Francisco Mime Troupe [SFMT], 1969), 30. Davis's arrest is portrayed in

the 1966 documentary film Have You Heard of the San Francisco

Mime Troupe? by Donald Lenzer and Fred Wardenburg, a copy of which

may be found in the Visual Materials Archives of the State Historical

Society of Wisconsin, Madison [SHSW].

2. In the best theoretical study

of the Sixties counterculture, Julie Stephens characterizes the product of

this interaction as constituting an "anti-disciplinary

politics." In her formulation, the term connotes "a language of

protest which rejected hierarchy and leadership, strategy and planning,

bureaucratic organization and political parties and was distinguished from

the New Left by its ridiculing of political commitment, sacrifice,

seriousness, and coherence." Stephens, Anti-Disciplinary

Politics: Sixties Radicalism and Postmodernism (Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press, 1998), 4.

3. Davis has ruefully

acknowledged that the Mime Troupe inadvertently "germinated all sorts

of mutants" who were inspired by his 1965 "Guerrilla

Theater" manifesto, namely the Diggers, the Yippies, and a phenomenal

number of agitprop street theater groups. The SFMT, 125. I

discuss the first two collectives in this essay, but, due to space

limitations, not the proliferation of guerrilla theater ensembles. This

last phenomenon has been examined at length by Henry Lesnick, ed., Guerrilla

Street Theater (New York: Bard/Avon, 1973); Karen Taylor Malpede,

ed., People's Theatre in Amerika (New York: Drama Book

Specialists, 1973); James Schevill, Break Out! In Search of New

Theatrical Environments (Chicago: Swallow Press, 1973); and John

Weisman, Guerrilla Theater: Scenarios for Revolution (Garden

City, N.Y.: Anchor Books, 1973). A short but useful discussion of the

variety, aims, and dramaturgy of such groups, and which acknowledges their

ultimate debt to Davis's seminal ideas, may be found in Richard Schechner,

"Guerrilla Theatre: May 1970," The Drama Review 14:3

[T47] (1970), 163-168. The role of radical theater groups during the era,

one which contrasts them with their counterparts of the 1930s, is

concisely given in Dan Georgakas, "Political Theater of

1960s-1980s," Encyclopedia of the American Left ed.

Mari Jo Buhle et al. (2nd ed.; New York: Oxford University Press, 1998),

614-616.

4. Mikhail Bakhtin, Rabelais

and His World. Trans. Helene Iswolsky (Cambridge, Mass.: M.I.T.

Press, [1968]).

5. Journalist Michael Goodman

confirmed that "the Mime Troupe was involved with a great deal of

what came to be known as the counter-culture... [including] the move into

the parks...." See his article, "The Story Theater, the Mime

Troupe, and a Political Rap with R.G. Davis," City magazine

[San Francisco] 5:40 (29 May-11 June 1974) 29. Davis himself observed that

when the Mime Troupe started performing in the parks in 1962 they were

"unique." But six years later, he noted, "there are rock

bands in the street and puppet plays and all kinds of things. ... We do

stimulate that kind of alternative." Davis, The San Francisco

Mime Troupe [hereafter The SFMT] (Palo Alto, Cal.: Ramparts

Press, 1975), 100; and excerpt from a panel discussion in Radical

Theatre Festival (San Francisco, Cal.: San Francisco Mime Troupe,

1968), 34. Also in this last source, Peter Schumann, the founding director

of Bread and Puppet Theatre, states that when his company began staging

plays in the streets of New York late in 1963, "it was new to New

Yorkers. They hadn't seen that since the twenties" [34].

6. See the short memoirs by

Serrano, "A Madison Bohemian," (pp.67-84) and Landau, "From

the Labor Youth League to the Cuban Revolution," (pp.107-112) in History

and the New Left: Madison, Wisconsin, 1950-1970, ed. Paul Buhle

(Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1970). Lee Baxandall's account,

"New York Meets Oshkosh," (pp.127-133) also discusses the

Anti-Military Balls; a script for "The Boy Scouts in Cuba," one

of the skits he co-authored, is included in the book's appendix

(pp.285-289). These early countercultural events bear investigating as

examples of politically tinged participatory theater. They were still

being staged later in the decade: Davis mentions giving a Mime Troupe

performance at an anti-military ball at Oregon State University in 1967.

See The SFMT, 112.

7. This is a mark of the high

esteem in which he held them. Judy Goldhaft, who was an early member of

the Mime Troupe, recalled that you couldn't exactly "join the company

at this time. [Davis] had to want to work with you." Author's

interview with Judy Goldhaft, San Francisco, Cal., 5 February 1993.

8. Author's interview with R.G.

Davis, San Francisco, Cal., 2 February 1993. The other source of Davis's

education in radical politics was the New School (West). Here for example,

is an account of one of his political epiphanies: "The New School

brought me into contact with the minds of the Bay Area. ... On April 22,

1964 we heard an indictment of the system and its objectives. The new Left

became concrete, my head buzzed for 20 minutes. ... Current political

insight is astounding." Untitled document written by Davis concerning

his activities in the year 1964, pp. 2-3, located in the SFMT archives,

box 2, Shields Library Special Collections Department, University of

California at Davis [PJSL].

9. Davis, "Guerrilla

Theater," originally published in the Tulane Drama Review

(Summer 1966) and reprinted in The SFMT, 149-153. On p. 70 he

states that when he read the first draft of this essay to the Mime Troupe

in May 1965, member Peter Berg suggested he title it "Guerrilla

Theater." The quotation by Che Guevara may be found in his book Guerrilla

Warfare trans. J.P. Morray (New York: Vintage/Random House, 1969

[1961]), 4, 32.

10. The text of Paul Potter's

speech was first published in the National Guardian (29 April

1965); an abridged version is in The New Left: A Documentary

History ed. Massimo Teodori (Indianapolis and New York: Bobbs Merrill

Co., 1969), 246-248.

11. Davis, The SFMT,

150.

12. This is the sine qua non

countercultural project as defined by sociologist J. Milton Yinger in his

study, Countercultures: The Promise and Peril of a World Turned Upside

Down (New York: Free Press, 1982). In his formulation a

counterculture consists of "a set of norms and values of a group that

sharply contradict the dominant norms and values of the society of which

that group is a part." Its competing normative system contains,

"as a primary element, a theme of conflict with the dominant values

of society." The development and maintenance of this system is the

result of a dynamic, on-going process that involves "the tendencies,

needs, and perceptions" of its members. The key idea here is that a

dialectical relationship exists between the countercultural group and the

larger society. The insurgent group develops a parallel set of norms and

values in opposition to, and can only be understood with

reference to, the surrounding society and its culture. Such a concept can

fruitfully be applied to any group, past or present, which devises not

only an ideology but an ethos and a set of practices that are

counterpoised to those of the dominant society, and then sustains them

through a relationship of calculated (though typically low-intensity)

conflict with that society.

13. Davis, "Guerrilla

Theater," in The SFMT, 150.

14. Coyote, Sleeping

Where I Fall; A Chronicle (Washington, D.C.: Counterpoint Press,

1998), 39, 41.

15. Davis, The SFMT,

57. See the undated comments (but ca. June 1965) directed to Davis from a

writer identified only as "Terry," who was a staff member of The

Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee of California; and also the

correspondence of SNCC field secretary Mike Miller from ca. summer 1966 in

the R.G. Davis papers, box 5, folder 6, State Historical Society of

Wisconsin Archives [SHSWA]. Miller's letter refers to the Mime Troupe as

"very good friends of the movement [in the Bay Area]—kind of the

movement's artistic arm." It is addressed to SNCC offices across the

country, notifying them that the SFMT is available to do local fundraising

benefits. The Troupe has continued to the present in offering this kind of

material aid to progressive organizations.

16. Richard F. Shepard,

"Mr. Interlocuter, Updated, Arrives; 'Minstrel Show' From Coast

Slashes at Racial Hypocrisy," New York Times (22 Oct.

1966), sec. 1, p. 36.

17. See the spring 1964 New

School prospectus in the SFMT archives, box 2, PJSL. The list of summer

1964 course offerings is in the R.G. Davis papers, box 1, folder 2, SHSWA.

Davis encouraged the members of his company to take classes at the New

School so that it would help them better to "comprehend the

political[,] psychological and social problems of a play." He also

looked to it as a potential source for recruiting actors and adding to the

Mime Troupe's audience base. See his notes for a company meeting dated 27

July [1964] in the Davis papers, box 4, folder 3, SHSWA. On the origins of

the New School, see Kirkpatrick Sale, SDS (New York:

Vintage Books, 1973), 265, 267.

18. Davis, "Guerrilla

Theater: 1967," originally published in the Boston-based underground

newspaper Avatar (1967) and reprinted in The SFMT,

154-155. Davis's rejection of bourgeois society has a familiar avant-garde

ring to it. Looking back from 1975, he acknowledged as much: "The

Mime Troupe moved from ... an avant-garde period ... to outdoor popular

theater ... and then onto radical politics, often preceding the political

awareness of its audience. ... When we were moving from the avant-garde to

a radical political stance, we retained the progressive spirit of the

avant-garde." Davis, "Politics, Art, and the San Francisco Mime

Troupe," Theatre Quarterly 5:18 (June-Aug. 1975), 26. As an

ideological analysis, the views he expressed in his second guerrilla

theater essay were being assimilated by the nascent counterculture in

1967. Cf. R. Larken and Daniel Foss: "The youth movement was not

merely against racism, the war or school administrations, but against the totality

of bourgeois relations [emphasis theirs]. It is easy to forget that

many took drugs ... to experience a reality that superseded and opposed

bourgeois reality." In The Sixties Without Apology, ed.

Sonya Sayres et al. (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota

Press, 1981), 360.

19. Davis, "Cultural

Revolution USA/1968," originally published in Counter Culture,

ed. Joseph Berke (London: Peter Owen, Ltd., 1969), and reprinted in The

SFMT, 156-164. Cf. Davis's incendiary rhetoric with that of H. Rap

Brown (later known as Jamil Abdullah Al Amin) in a speech delivered in

Cambridge, Md., on 24 July 1967: "Black folks built America, and if

America don't come around, we're going to burn America down."

Transcript of "The Cambridge Speech," Page Collection of H. Rap

Brown Materials, Accession no. MSA SC 2548, Maryland State Archives

Special Collections.

20. Peter Berg interview in Ron

Chepesiuk, Sixties Radicals, Then and Now: Candid Conversations

with Those Who Shaped the Era (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co.,

1995), 118-132 at 128.

21. Marie Louise Berneri,

"Utopias of the English Revolution: Winstanley, The Law of

Freedom," in her book Journey through Utopia (London:

Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1950), 143-173; quote taken from Winstanley's

text appears on p. 149. The complete document may be found in his The

Works of Gerrard Winstanley ed. George H. Sabine (Ithaca, N.Y.:

Cornell University Press, 1941).

22. Davis, the

"Handbook" section of his essay, "Guerrilla Theater:

1965," in The SFMT: "Start with people, not

actors. Find performers who have something unique and exciting about them

when they are on stage. ... Liberate the larger personalities and

spirits" [151]. "Amateurs can be used if you cast wisely. ...

Ask a painter to do a backdrop or a sculptor to make a prop. ... If you

need ... new material, find writers, politicos, poets to adapt material

for your group. ... The group must attract many different types of

people" [152].

23. Davis seems to have

respected the theatrical talents of only a few of these. The rest

he put down hard in 1975. In a pointed remark about "the street hoods

... without skills who should not have been in the company,"

(apparently referring to Diggers who had left the Mime Troupe between

1966-1968), he archly dismissed them thus: "They left ... to work

elsewhere, not in art but in craft." Davis, The SFMT,

125.

24. Author interviews with Peter

Berg and Judy Goldhaft, 24 November 1992, Ithaca, N.Y., and 5 February

1993, San Francisco.

25. Interview with Jane Lapiner

and David Simpson, 27 and 28 February 1994, Petrolia, Cal.

26. During the Summer of Love, an

apartment in the Haight could be leased for $90 and a three-story,

eleven-room house for as little as $210. Stephen A.O. Golden, "What

Is a Hippie? A Hippie Tells," New York Times (22

August 1967), sec. 1, p. 26.

27. "New Community" was a

term used by Haight-Ashbury hippies and avant-gardists to proclaim their

collective identity in situ beginning about 1966. The adjective

signified both their status as newcomers to the neighborhood and their

conceit that what they were attempting was without precedent. The noun was

as much aspirational as descriptive: theirs was at that time very much a

community in the process of coalescing. In retrospect the term was

self-representative of only the first phase of the Haight-Ashbury

counterculture; one does not encounter it in the historical record after

the Summer of Love. By that time, of course, the sense of novelty had

passed, but also the notion of a hip community in the Haight was regarded

as an established if contested reality. [Clint Reilly], "Editorial:

The New Community," Middle Class Standard 1:1 (16 July 1967)

1. A copy of this newsletter is filed in the San Francisco Hippies

collection, box 2, folder "Middle Class Standard," San Francisco

Public Library Special Collections Department (SFPL). The earliest

appearance of the term that I have located is in the Communication Company

broadsheet entitled "Press Release 1/24/67," filed in the New

Left collection, box 32, folder: "Digger Papers - 1967," Hoover

Institution on War, Revolution and Peace, Stanford University [HIWRP]. See

also David E. Smith and John Luce, "The New Community," part II

of Love Needs Care: A History of San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury Free

Medical Clinic and Its Pioneer Role in Treating Drug-Abuse Problems

(Boston: Little, Brown, 1971), 73-148; and Charles Perry, The

Haight-Ashbury: A History (New York: Rolling Stone/Random House,

1984), 131.

28. Chester Anderson, a

self-identified Digger and co-founder of the Communication Company, used

this exact phrase ("Force them to be free") in an untitled

broadsheet, the first line of which is "Every time somebody has

turned on a whole crowd of people at once, by surprise[...]," dated

28 Jan. 1967. Here the context is different but its intention remains

arrogantly coercive. He urges his fellow acid heads to commit

"psychedelic rape"; i.e., surreptitiously introduce non-users to

LSD without their foreknowledge or consent out of the misbegotten

certainty that it will promote "social evolution," and even

"save the world." Filed in the Social Protest collection, carton

6, folder 10, Bancroft Library, University of California at Berkeley

[BANC]. This same approach had already been taken by The Merry Pranksters

in their "acid test" happenings beginning in fall 1965. See Tom

Wolfe, The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test (New York: Bantam

Books, 1968), especially 241-253.

29. In the 1966 primary election,

Scheer had come close to wresting away the Democratic Party nomination

from Cohelan. William J. Rorabaugh, Berkeley at War: The 1960s (New

York: Oxford University Press, 1989), 99-104. Scheer was an antiwar

activist and journalist for Ramparts, who was also a close

associate of SFMT director R.G. Davis. The puppets had been made by

sculptor Robert La Morticella (a Digger who was arrested in this Public

Celebration) for the SFMT skit Congressman Jeffrey Learns of

Robert Scheer which was performed on the UC-Berkeley campus during

the fall of 1966.

30. Davis was reinforced in his

meritocratic attitudes on this score by Saul Landau. In a note Davis made

of a conversation that Landau had had with him on 19 April 1965 (around

the time that he was drafting the Guerrilla Theater essay), he paraphrased

Landau as saying: "We are dealing with amateurs [in the Mime Troupe]

who do not act as professionals, ... [who] have that attitude about

theater that ... smacks of the unconcerned. ... Amateurism is death to the

growing theatre." Typescript document by Davis entitled "1965

Notes/Letters," in Peter J. Shields Library Special Collections

Department, University of California, Davis, San Francisco Mime Troupe

Archives, box 2.

31. The Reverend Thomas King Forcade,

"Abbie Hoffman on Media," in The Underground Reader ed.

Mel Howard and Thomas King Forcade (New York: New American Library, 1972),

68-72 at 69. This interview was recorded in Ann Arbor, Mich., in July

1969, and was originally published in the Vancouver, B.C., underground

newspaper The Georgia Straight.

32. The evidence for this claim may be

examined in ibid., passim. Other authors, while acknowledging the

Haight-Ashbury Diggers' impact on Abbie Hoffman in particular, have

instead stressed multiple sources of influence on the New York scene, not

privileging any single source. See especially Marty Jezer, Abbie

Hoffman, American Rebel (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University

Press, 1992); Jack Hoffman and Daniel Simon, Run, Run, Run:

The Lives of Abbie Hoffman (New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1994);

Jonah Raskin, For the Hell of It: The Life and Times of Abbie Hoffman

(Berkeley, etc.: University of California Press, 1996), as well

as Hoffman's own memoir Soon to Be a Major Motion Picture

(New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1980).

33. Howard Smith, "Scenes"

col., Village Voice 12:42 (3 August 1967) 11; ibid.

12:43 (10 August 1967) 7; photos by Fred W. McDarrah and captions on pp.

1, 25.

34. Marty Jezer, Abbie

Hoffman, 111-112.

35. Leticia Kent, "Evangelizing

Wall Street: Square Sales & Odd Lots," Village Voice,

vol. 12, no. 46 (31 August 1967) 3; John Kifner, "Hippies Shower $1

Bills on Stock Exchange Floor," New York Times (25 August

1967), sec. 1, p. 23, accompanied by a photo of group members tossing the

money from the gallery. [Abbie Hoffman is plainly visible in this

picture.] See also the untitled account by the pseudonymous "George

Washington" [journalist Marty Jezer who also observed the event], in WIN

magazine, vol. 3, no.15 (15 September 1967), 9-10, and Jezer's later

account in Abbie Hoffman, 111-112. Hoffman's version is in his

book Revolution for the Hell of It (New York: The Dial Press,

1968), 32-33, where it is misdated to 20 May 1967. Setting fire to dollar

bills was another practice popularly associated with the Haight-Ashbury

Diggers. George P. Metesky [occasionally the Diggers misspelled it Metevsky]

was dubbed the "Mad Bomber" by the New York press when in the

1950s he conducted a seven-year bombing campaign throughout the city

primarily aimed at the interests of Consolidated Edison. Metesky was most

frequently used as a pseudonym by Haight-Ashbury Digger and Brooklyn

native Emmett Grogan as part of the collective's commitment to anonymity.