|

| |

Kaliflower & the Homosexual Revolution of 1969

Intersecting Lives & the Rise of the Gay Liberation Movement in San

Francisco

Presentation to Burrow’s Bees Pandemic Zoom, September 24, 2023 (watch the

video recording here).

Some may question the juxtaposition of LGBTQ+ history and the Diggers. My

argument is that the San Francisco Diggers spawned a movement that spread

outward into the counterculture. Among the ripple effects in the San Francisco

Bay Area was the emergence of a group of communes devoted to Digger Free and

the vision of "Post-Competitive

Game of Free City" long after the Summer Solstice of 1968 brought down the

curtain on the original Digger energy in San Francisco. Many of these communes

were queer identified. It is critical to not overlook this crossover between

Digger and Queer history.—en

HOW TO ZOOM the images: click on any image to ZOOM IN; then click the full-size

image to ZOOM OUT.

|

This project has been percolating a while. In our zoom group over the

past three years, we have talked about many of the people and groups in

this history, but never as a series of interconnected points along an

arc of social history. So, this presentation is an attempt to connect

Kaliflower, both the commune and the newspaper, with the emergence of a

radical queer sensibility in San Francisco. Everyone knows about

Stonewall and what happened in June of 1969 in New York City. But not

many know what happened in San Francisco several months earlier.

Stonewall has become that watershed moment that divides two eras in the

history of queer freedom. As well it should be. However, as we will see,

a fully articulated notion of gay liberation had been formulated in San

Francisco months before Stonewall. And the interesting aspect of this

research is how it intersects with the history of Kaliflower.

|

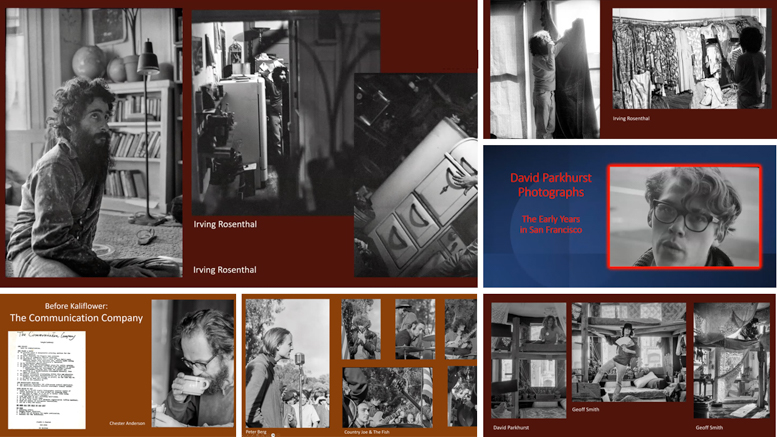

The presentation of David Parkhurst’s recently uncovered photographs from 1967

to 1970 inspired this talk. David narrated the photos that Joseph Johnston had

developed from the long-lost negatives. David told how he first arrived in San

Francisco at the height of the Summer of Love. He has photos of the

Communication Company, the Diggers, Straight Theater people, and later the

Sutter Street Commune. One of David’s stories prompted me to do a deep dive

researching this presentation. David told how he was brought to the commune by

Dunbar Aitkens after the two of them ran into each other on Haight Street in

March 1969. One of the oddities of the story is that David and Dunbar ran into

each other in 1969 on the exact same corner as they had two years previously. On

both occasions, Dunbar was handing out leaflets about the current project he was

pursuing. On this second occasion, David remembers that Dunbar was handing out a

leaflet announcing a free university for communes.

|

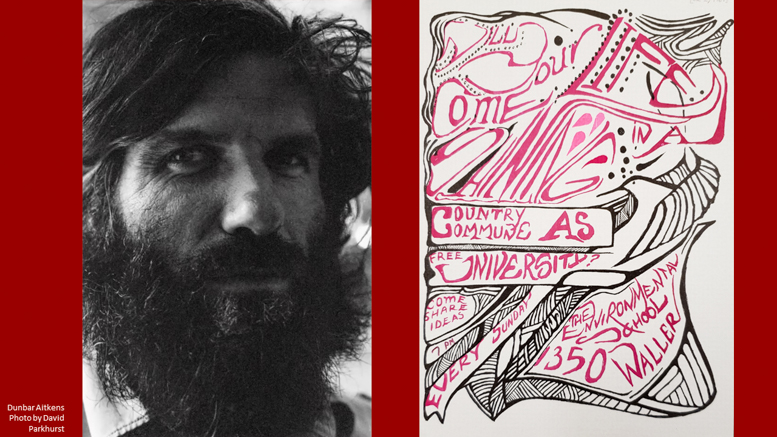

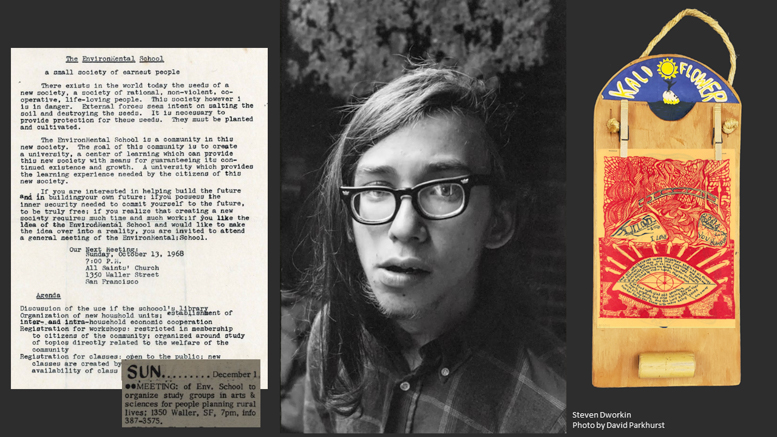

The flyer on the right is for “The Environmental School Free University” —

Dunbar’s project when he and David randomly met each other in 1969. David’s

recollection of Dunbar set me off on this research trail and it turns out that

Dunbar intersects this history at several points. The best description of Dunbar

comes from Irving Rosenthal’s memoir for the tenth anniversary issue of

Kaliflower. Irving wrote:

“I saw Dunbar Aitkens on Haight Street handing out mimeographed sheets

long before I met him, and I met him long before he moved into the commune.

Dunbar was a huge, tall, blackhaired street philosopher, as gentle as a

bunny. He was very interested in young men, and had the knack for meeting

them easily on the street. He always had some interesting project going to

talk to them about. He brought many of them to the commune, both before,

during, and after the month he lived with us (March-April 1969), to the

point where the word “indunbaration” was coined to describe the phenomenon.

At the time he came to live with us he was trying to form a sort of rural

commune called the Environmental School, along with Stevie and Teddy, whom

he brought into the commune with him. Other Dunbar-recruited members were

Art, Carl, Arthur, Sam, and David. Dunbar hotly denied any religious

outlook, but I always saw him as a roving guru, making spiritual contact on

the street.”

As Irving mentioned, Dunbar was responsible for David Parkhurst moving into

the commune. At their chance meeting on Haight Street, Dunbar told David he was

living in a commune, and he should come by to visit. That was the Sutter Street

Commune, which had set up and was operating the Free Print Shop after the Diggers

convinced Irving to bring his press from New York. The flyer announcing Dunbar’s

Free University project was printed by the Free Print Shop.

|

Steven Dworkin was another one of Dunbar’s recruits for the commune. In late

1968, Steven attended Dunbar’s weekly gatherings for the Environmental School

that were held at the All Saints Church on Waller Street. As an aside, this

church was one of the locations out of which the Diggers had operated. It was

where Walt Reynolds taught the Diggers how to bake whole wheat bread in

discarded coffee cans. In late 1968, at one of Dunbar’s meetings, the Sutter

Street commune showed up to check out the Environmental School Free University.

This is when Dunbar and Steven met the commune. Dunbar soon decided to accept

the commune’s invitation to move in, and Steven followed within a short time.

With a little prompting, Steven had a brainstorm idea for a new project —

to publish an intercommunal newspaper to stay in contact with other communes in

the Bay Area. He named the newspaper Kaliflower as a pun on the term Kali Yuga

which, in Hindu cosmology, is the end times of destruction.

The first issue of Kaliflower was April 24, 1969. It was distributed to a

handful of communes. A copy of the first issue can be seen hanging from

clothespins on the Kaliflower plywood board, another of Steven’s inventions.

Each commune would have a Kaliflower board hanging in the kitchen where the

weekly issue would be attached. The cover of this first issue would set the tone

for the homoerotic imagery that became one of the hallmarks of Kaliflower. Even

though the commune was a mix of sexual orientations, it had the reputation of

being a gay commune. With creatures like Hibiscus and Jilala and Ralif dressing

up and performing as the Kitchen Sluts while preparing the communal meal every

night, it’s hard not to see how that reputation was gained. Over the period of

three years of continuous weekly publication, Kaliflower grew from a handful to

more than 300 communes that received the Free newspaper which was hand delivered

every Thursday.

|

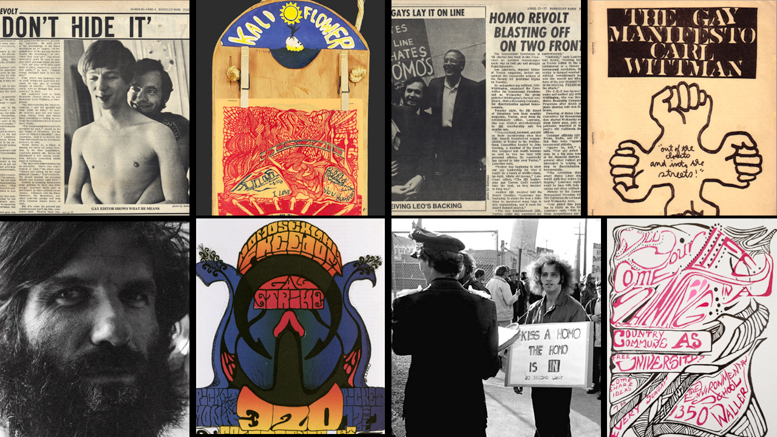

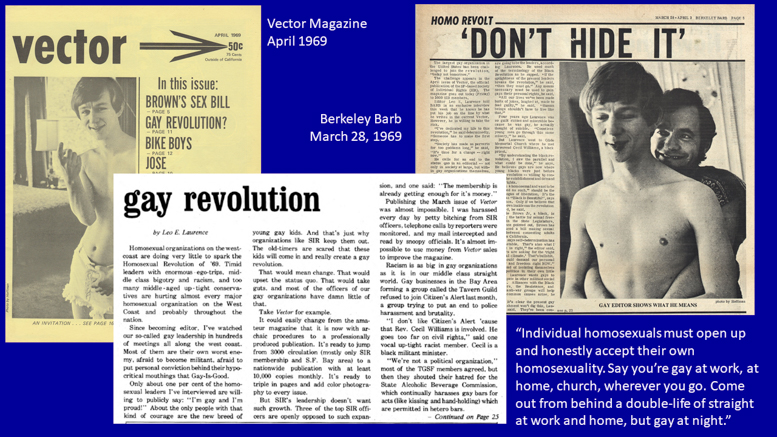

Meanwhile, in the same week as the first issue of Kaliflower, an essay appeared

in Vector calling for gay revolution. Vector was the publication of S.I.R., the

Society for Individual Rights, one of the half dozen homophile organizations at

the time. S.I.R. was founded in San Francisco in 1964 after police closed a

dozen bars with gay and lesbian customers. By 1969, S.I.R. had more than a

thousand members. In the April 1969 issue of Vector, the magazine’s new editor,

Leo Laurence, wrote a column in which he called for a radical new approach to

gay rights. He criticized gay establishment organizations, including S.I.R., for

their cautious attitudes toward radical advocacy, getting waylaid by ego-trips

and hypocrisy. He criticized the Tavern Guild for racism, citing their

opposition to Cititzen’s Alert, a project initiated by the Reverend Cecil

Williams, the Black head minister of Glide Church to end police harassment and

brutality. Laurence ended his essay with a clarion call that rang loud, and

which foreshadowed similar language a decade later from Harvey Milk. Laurence

wrote, “Individual homosexuals must open up and honestly accept their own

homosexuality. Say you’re gay at work, at home, church, wherever you go. Come

out from behind a double-life of straight at work and home, but gay at night.

I’ll admit it's not easy to be honest, but neither was writing this article.”

The same day that the April issue of Vector hit the newsstands, the Berkeley

Barb published an article that reported on its revolutionary message. Its lead

in sentence read, “The largest gay organization in the United States has been

challenged to join the revolution ‘today not tomorrow.’” In the photo

accompanying the article appeared Leo Laurence with his arms embracing a young

shirtless friend who was unnamed.

|

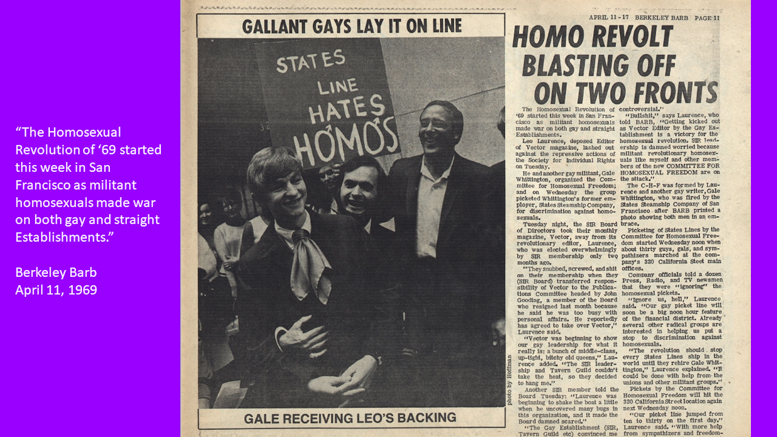

At this point, things start to move into high gear. The young friend who had

appeared shirtless in the Berkeley Barb was Gale Whittington, an employee of the

States Steamship Company at their headquarters in San Francisco’s financial

district. Whittington was fired from his job the week after his photo appeared

in the Barb. Laurence and Whittington then decided to form a group to protest

the firing by holding a daily picket line in front of the Steamship Company

offices on California Street. They named their group the Committee for

Homosexual Freedom. Here’s an article in the Berkeley Barb with a report of the

protest. The article announced that, “The homosexual revolution of 1969 started

this week in San Francisco as militant homosexuals made war on both gay and

straight Establishments.” The article also reported that the Board of Directors

of S.I.R. had dismissed Leo Laurence as editor of Vector, a post he had held for

only two months.

|

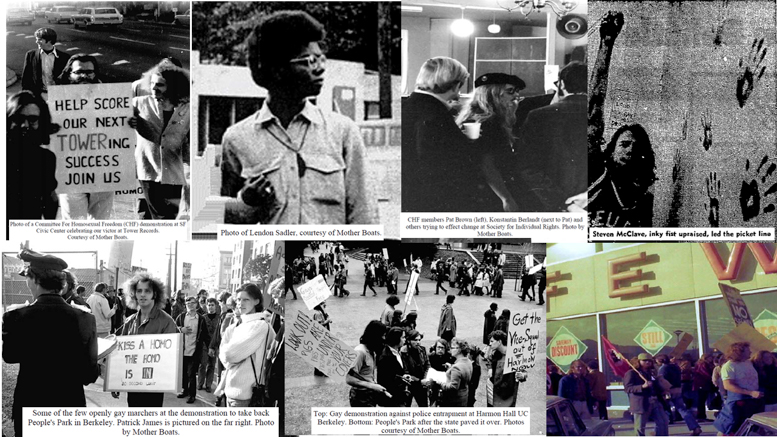

The next two slides depict many of the subsequent protest actions that the

Committee for Homosexual Freedom carried out in the spring, summer, and fall of

1969. Aside from the daily picket lines in front of 320 California Street to

protest the firing of Gale Whittington from his job, the committee joined or

initiated protests all over the Bay Area. This first slide is all photos of the

California Street picket line in front of the States Steamship headquarters. The

photo of the Financial District businessmen standing around is humorous on a

couple of levels. Whittington captions the photo “bankers across the street

appear infatuated.” If anyone remembers the Digger film NOWSREAL, there is a

similar scene. On the Summer Solstice 1968, one year earlier than these photos,

the Diggers drove up Montgomery Street with a troupe of belly dancers performing

on a flat bed truck. In the film, a gaggle of businessmen stand on the sidewalk

ogling the dancers. The fashion of the businessmen hadn’t changed in one year

although the protesters certainly had.

|

The Committee for Homosexual Freedom was very active in the following months of

1969, holding picket lines at Tower Records in San Francisco to protest the

firing of another gay employee; showing up with pro-gay signs at the People’s

Park demonstrations; picketing Safeway in solidarity with Cesar Chavez and the

Grape Boycott of the Farm Workers union. The campus at UC Berkeley, like for so

many movements in the past decade, was an ideal location for getting their

message out. One of the photos here was taken at Sproul Plaza protesting police

entrapment of gays on campus. Committee members also showed up at S.I.R.

meetings to lobby for more progressive policies. Also included is a photo of

Lendon Sadler, an active member of the Committee, to show what he was doing

before his involvement with the Cockettes the following year.

The photo at top right depicts a protest at the San Francisco Examiner on

October 31, 1969. The Committee for Homosexual Freedom set up a picket line to

protest an article by Robert Patterson, an Examiner reporter, that purported to

be an expose of San Francisco’s gay clubs where “homosexuals gather for their

sick, sad revels.” As the picket line proceeded in front of the Examiner

building on Fifth Street, with chants of “Say It Loud, We’re Gay and We’re

Proud,” suddenly a bag of purple printer’s ink was hurled over the roof onto the

protesters. The picketers proceeded to dip their hands into the ink and leave

handprints and slogans on the side of the building. At this point, the Tactical

Squad was called in and a dozen arrests were made. The Chronicle report of the

protest noted that “the homosexuals … prefer to be called gay.” In subsequent

reports of the arrests and follow-up court hearings, the name of the organizing

group shifted from the Committee for Homosexual Freedom to the Gay Liberation

Front. The reason for this change in nomenclature will become clear with the

next slide.

|

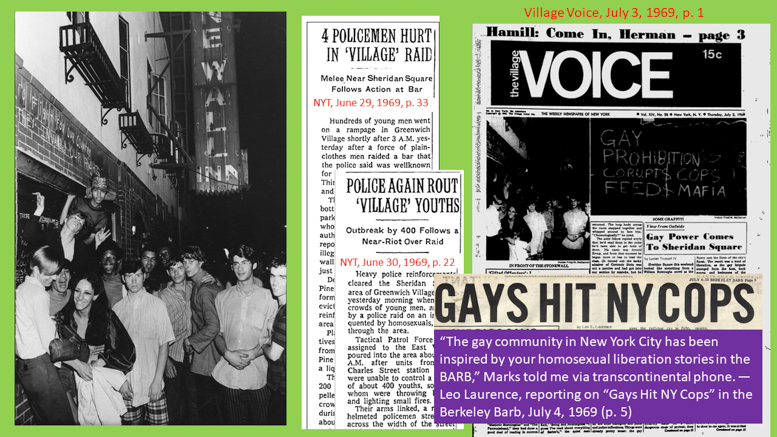

Remember that the first action of the Committee for Homosexual Freedom took

place in the first week of April 1969, nearly three months before Stonewall. Of

course, the events that happened in New York City in the early midnight hours of

June 28 would become a prime focus for historians of the Gay Liberation

movement. For a historian of social movements, it’s often an exercise in

futility to try and pinpoint causality. Did the events in San Francisco three

months prior to Stonewall play any part in the events that hot summer night in

Greenwich Village three thousand miles away? In reading through the underground

press, the only mention of the Committee for Homosexual Freedom in San Francisco

was the articles in the Berkeley Barb. I found nothing in the East Village

Other, for example, one of the sister underground papers that all shared their

stories through the Underground Press Syndicate.

But there are two tantalizing bits of evidence of a connection. Leo Laurence

reported on the Stonewall Uprising in the July 4, 1969, issue of the Berkeley

Barb. In the story, he reported talking with J. Marks, an eyewitness to the

second night’s events. Laurence quoted Marks as saying, “The gay community in

New York City has been inspired by your homosexual liberation stories in the

BARB.” Gale Whittington in his memoir states that “several” Stonewall activists

contacted the San Francisco group to say they took inspiration from the militant CHF activities that spring. “They said if we could do it here, they could stand

up for their rights there.” One of the outcomes of the Stonewall Uprising in

June was that a group of activists in New York City came together two nights

later and formed the Gay Liberation Front which had a more pronounced

revolutionary ring to it than Committee for Homosexual Freedom. Over the next

few months both CHF and GLF were used interchangeably until finally GLF became

the name of choice.

|

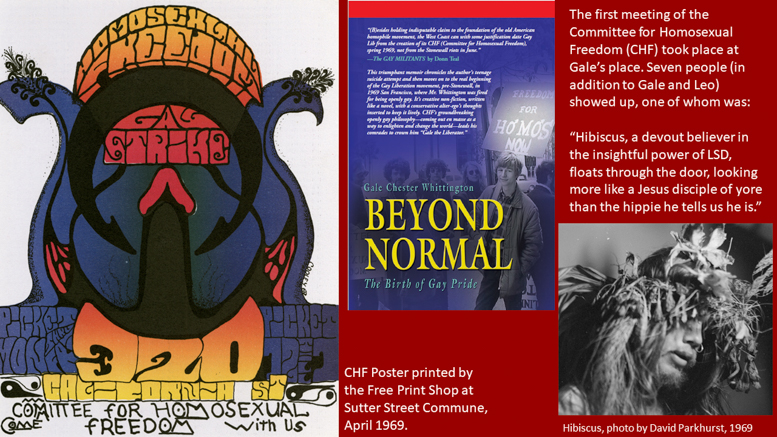

At this point, some of the intersecting connections in this story start to

resolve. One of those connections is this poster which the Free Print Shop

printed for the Committee for Homosexual Freedom early on for the picket line at

the States Steamship company. This poster is so interesting to me because it

represents a crossover between the queer and hippie cultures. The homoerotic

imagery combined with the psychedelic lettering and design is emblematic of the

mix between these two subcultures in San Francisco. At the Cockettes 50th

anniversary celebration, John Waters talked about the first time he attended one

of the Cockettes shows at the Palace Theater. Waters said, “I was so amazed at

the audience which was as shocking as the show. Hippie gay guys, finally! It was

so great to see them, you know. And drag queens with beards reading Lenin.”

Can people read the psychedelic lettering? “Homosexual Freedom / Gay Strike /

Picket Mon Thru Fri / 12 till 1 / 320 California Street / Committee for

Homosexual Freedom / Come With Us.” I have always wondered what the connection

was between the Sutter Street commune, the Free Print Shop, and the Committee

for Homosexual Freedom. The artist signed their work so someone brought the

design to the commune to print.

In preparing this talk, I discovered that Gale Whittington published a memoir in

2010. It contains a day-by-day account of his firing and subsequent actions.

After he was fired from his job when his shirtless photo appeared in the

Berkeley Barb, Gale and Leo Laurence went to complain to Max Scherr, the

publisher of the Barb. Scherr had used the photo without Gale’s or Leo’s

permission. Instead of apologizing, Scherr roused the two to action, suggesting

they protest the firing. That’s when Leo and Gale decide to form the Committee

for Homosexual Freedom. At their first organizing meeting, seven people showed

up besides the two founders. One of these new members was Hibiscus who was still

living in the Sutter Street Commune. Gale describes Hibiscus as “a devout

believer in the insightful power of LSD.” According to Whittington, Hibiscus was

a regular participant in the committee’s protests, at one point defusing a group

of teenagers bent on attacking the group by tearing off the placard of his

protest sign and leaving just the wooden picket to defend himself. The teens got

back in their cars and sped off.

Was Hibiscus the connection between the Committee for Homosexual Freedom and the

Free Print Shop’s printing of the crossover queer hippie poster? We can only

speculate. No one from the commune that I have asked remembers this poster. But

that’s not unusual given the amount of printing that was happening and the

weekly schedule for publishing Kaliflower.

|

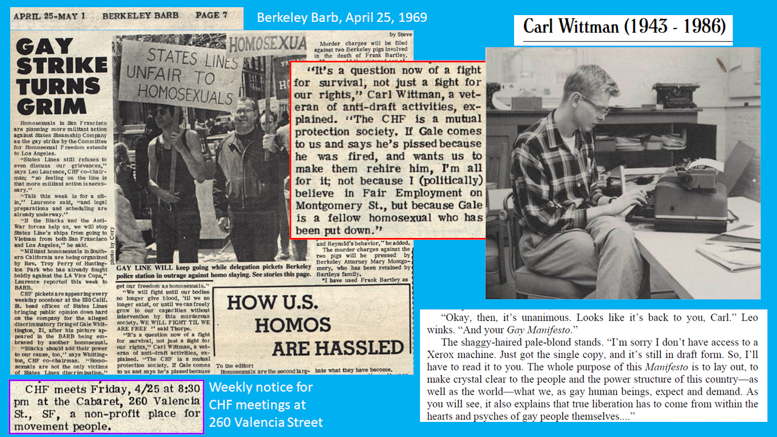

The next person whose story intersects with this history is Carl Wittman, who

was living in San Francisco when the Committee for Homosexual Freedom started

picketing States Lines. Carl had been a campus organizer for SDS, Students for a

Democratic Society, before coming out as gay and coming out to the West Coast.

Within the first week of the picketing, Carl showed up to join in. He announced

to the group that he was writing a manifesto of gay liberation and wanted to

share it with everyone. Here is an article from the Berkeley Barb two weeks into

the picketing that reports on the group’s plans to increase pressure on the

Steamship line. It is also the first article that quotes Carl Wittman who said,

“It’s a question now of a fight for survival, not just a fight for our rights.

The CHF is a mutual protection society.” In the lower left is one of the weekly

notices that appeared in the Berkeley Barb announcing the meetings that the CHF

held at 260 Valencia Street in San Francisco’s Mission district. Gale

Whittington in his memoir names many of the early members of the radical group.

I’ve mentioned Hibiscus but others included Pat Brown, a “self-proclaimed

Trotskyite hippie”; Charles Thorpe, Stephen Matthews, Morgan Pinney, Sheeza

Mann, Darwin Dias, Lendon Sadler, and Konstantin Berlandt. Carl got to read a

draft version of his manifesto to the group at one of their meetings. Gale

Whittington recalled Carl’s introduction, “The whole purpose of this Manifesto

is to lay out, to make crystal clear to the people and the power structure of

this country — as well as the world — what we, as gay human beings, expect and

demand. As you will see, it also explains that true liberation has to come from

within the hearts and psyches of gay people themselves.”

|

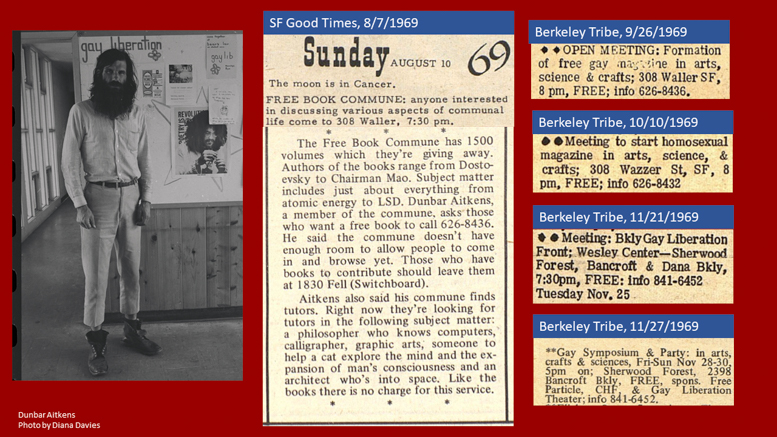

At this point, Dunbar Aitkens reemerges on the arc of this history. Recall that

Dunbar had lived briefly at the Sutter Street Commune just as Kaliflower, the

intercommunal newspaper, began publication. Dunbar, as Irving said, “always had

some interesting project going.” After he left the commune, we can pick up

traces of his activities in the summer and fall of 1969 through notices he

placed in the underground newspapers. His first project was a Free Book commune

he started on Waller Street. They collected and gave away books to all comers.

Here’s an article in the San Francisco Good Times that describes the range of

books they were giving away “from Dostoevsky to Chairman Mao.” Within a month,

Dunbar had started putting up notices for meetings at his commune to discuss a

journal of the arts, science and crafts by and for homosexuals. Finally, in late

November, Dunbar announces a weekend-long Gay Symposium and Party at Sherwood

Forest, the informal name for the Methodist student center across from the

Berkeley campus. Notice that the sponsors of the Gay Symposium are listed as

Free Particle, CHF and Gay Liberation Theater. Free Particle was Dunbar’s

journal by and for homosexuals. CHF of course was the Committee for Homosexual

Freedom. Gay Liberation Theater was a collective that included Gale Whittington

who were performing street theater on the Berkeley campus.

|

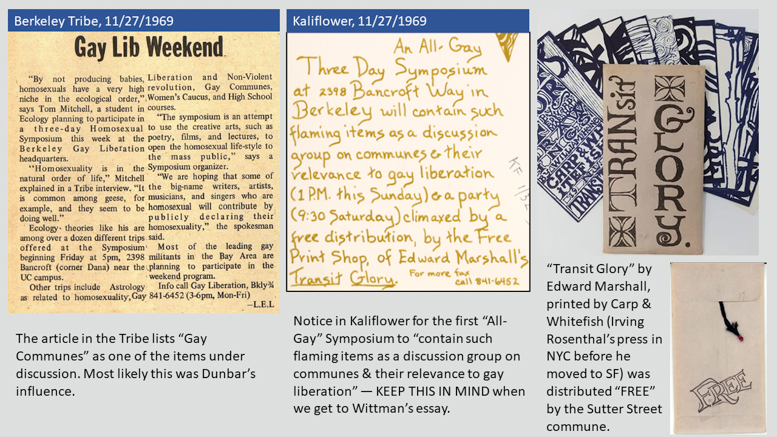

Here are two other notices about the first Gay Symposium that Dunbar and others

organized for the weekend of November 28-30, 1969. The Berkeley Tribe mentions

that topics to be covered include gay communes. The notice in Kaliflower states

that the symposium will “contain such flaming items as a discussion group on

communes and their relevance to gay liberation.” This symposium was where the

Sutter Street Commune distributed Edward Marshall’s book Transit Glory. Anyone

who heard my talk on the life and times of Irving Rosenthal may recall that this

was one of two Beat poetry books that Irving printed in New York in 1967 at his

Carp & Whitefish press and which presented a dilemma for Irving when he

converted to the Digger Free philosophy. Ultimately, the poet and writer Richard Brautigan convinced Irving to give away both books for free. The commune

distributed the Whelan book, Invention of the Letter, during a Free City poetry

reading at Glide Church the year before. Notice the envelope in which the

individual cards that made up the Marshall book were enclosed. The label FREE

was stamped on by the commune to signify its liberation from the world of

commerce. Nevertheless, Transit Glory is much sought after by collectors today

and fetches hundreds of dollars in the rare book market.

|

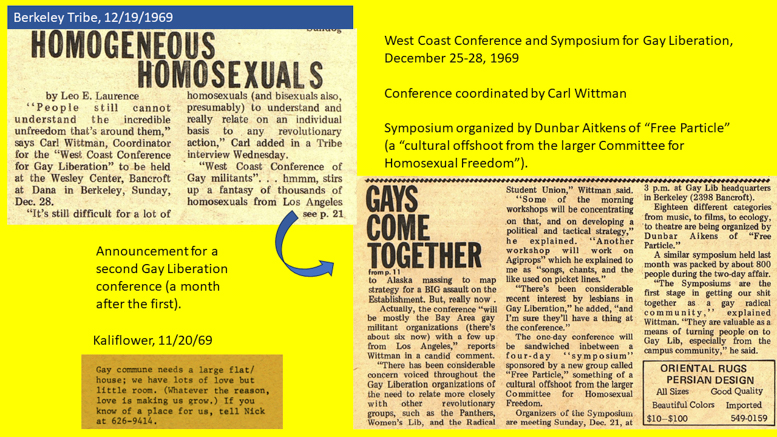

The Berkeley Barb reported that the attendance at the All-Gay Symposium was over

800 people. Success breeds success. A month later, a second All-Gay gathering

took place. This time, all three of our actors came together in pulling off the

event. Carl Wittman coordinated a one-day conference sandwiched in between the

four-day symposium organized by Free Particle. In turn, Free Particle is

mentioned as an offshoot of the Committee for Homosexual Freedom. Carl Wittman

is quoted saying, “The symposiums are the first stage in getting our shit

together as a gay radical community. They are valuable as a means of turning

people on to Gay Lib, especially from the campus community.” So sayeth the ex-SDS

organizer.

|

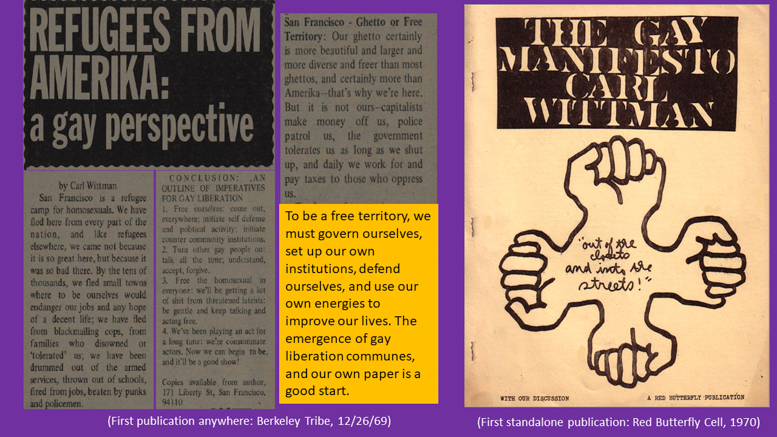

As if to bring this first phase of the homosexual revolution to a resounding

close, Carl Wittman’s essay was published on December 26, 1969, the same week as

the second All-Gay Symposium. After its first appearance in print in the

Berkeley Tribe, Carl’s essay was reprinted in numerous underground newspapers,

anthologies, magazines and standalone pamphlets. The Tribe published Carl’s

essay with a title, “Refugees from Amerika: a gay perspective.” The word America

was spelled with a K as was common in the radical 60s. In future reprintings,

the essay would be called simply "The Gay Manifesto." It has been described as

“the Bible of gay liberation” by some historians. I have highlighted what I

think is the crux of Wittman’s idea: “To be a free territory, we must govern

ourselves, set up our own institutions, defend ourselves, and use our own

energies to improve our lives. The emergence of gay liberation communes, and our

own paper is a good start.”

Attempting to unpack that statement is what this whole presentation has been

about. In that one sentence we see echoes of the Digger Free City project, the

Kaliflower intercommunal project, and the queer aesthetic and radical program

that emerged in the spring of 1969 in San Francisco and burst forth on the

national stage in New York a few months later. Was Wittman specifically

referencing Kaliflower? We cannot and may never know the answer to that

intriguing question. However, it is clear that the culture which Kaliflower,

both the commune and the newspaper, was attempting to build certainly fits into

Wittman’s vision for the queer community.

|

The publication of Carl Wittman’s “Gay Manifesto” might be considered the end of

this story but of course there is never an ending to any story even if

reverberations are all that remain. Echoes of the Homosexual Revolution of 1969

would continue to reverberate for decades.

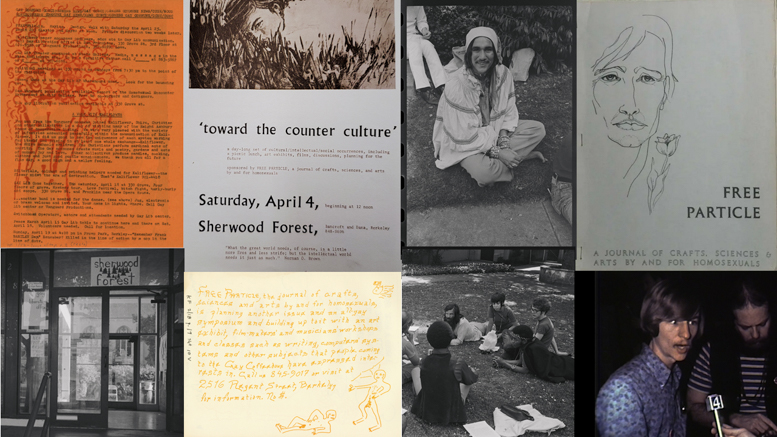

This slide depicts a few of those echoes from the following

year, 1970. From top left, the orange sheet was a report on Gay Commune

Consciousness that was distributed with an issue of Kaliflower. The

poster for the event ‘toward the counter culture’ was printed by the Free Print

Shop at the Sutter Street Commune. It announced a “day long set of

cultural/intellectual/social occurrences” sponsored by Free Particle to

take place at Sherwood Forest. The three black and white photos are from that

event. The bottom left shows the informal name Sherwood Forest hanging over the

doorway of the Wesley Center. The bottom black and white photo shows Dunbar in a

group discussion on the lawn and the top photo shows Tahara who would become one

of the core members of the Angels of Light Free Theater commune.

In the same month as this symposium, the first and only

issue of Free Particle appeared, the cover of which is shown here. The

publication ran 60 pages and contained a wide range of topics. One of the most

interesting pieces is a script for one of the street theater skits that the Gay

Liberation Theater collective performed in Sproul Plaza in October 1969. Street

theater in the Sixties was so often improvisational that it is rare to find full

scripts. That this was also associated with the emerging gay liberation movement

makes it all the more valuable.

In the lower row in yellow ink is an ad from Kaliflower

announcing a Gay Coffee House and mentioning plans for another issue of Free

Particle but it never happened. By that point, Dunbar was off to other

pursuits. Carl Wittman was off to Oregon to live in a country commune and put

his literary skills in the service of RFD magazine. Gale Whittington never got

his job back and eventually left San Francisco for Colorado but not before

further rabble rousing as a gay activist. Gale is seen in the lower right being

interviewed by a local news station during a sit-in at the mayor’s office

protesting San Francisco police brutality against gays. This was a film clip

from a TV news archive that David Weissman and Bill Weber used in their

documentary film The Cockettes. Little did they know who Gale Whittington

was. In his memoir, Whittington proudly mentioned his appearance in The

Cockettes film not realizing that his role in the rise of gay liberation had

been lost to history.

With this presentation, I hope to have reconnected the intersecting lives and

roles that Leo Laurence, Gale Whittington, Dunbar Aitkens, and Carl Wittman

played in our collective history.

|

If you enjoyed this presentation, be sure to check out my website, The Digger

Archives, dedicated to keeping people’s history alive. To end this video, I want

to play an excerpt from a song* that embodies the sentiment that Leo Laurence

first announced in his Vector editorial half a century ago, “Individual

homosexuals must open up and honestly accept their own homosexuality. Say you’re

gay at work, at home, church, wherever you go.” The next screen is a listing of

some references for anyone who wants to follow up on the sources for this talk.

*A short excerpt of Lady Gaga’s “Born This Way” played over the last slide.

|

References

- Berkeley Barb available at

Independent Voices of JSTOR

- Beyond Normal: The Birth of

Gay Pride by Gale Whittington (self-pub., 2010) Kindle.

- Carl Wittman references:

- David Parkhurst Photographs (digital copies available offline

through photographer)

- Diana Davies

photographs of Berkeley Gay Symposia, at New York Public Library

- Free Particle, a Journal of Crafts, Sciences & Arts By and For

Homosexuals, April 1970 (available offline at the Digger Archives)

- Free Print Shop Archives

catalog

- Kaliflower,

the Intercommunal Newspaper

- On Christopher Street: Life,

Death, and Sex After Stonewall by Michael Denneny (University of Chicago Press,

2023)

- “The Gay Manifesto” by Carl

Wittman (available online at the University of Washington library

- The Stonewall Riots: A

Documentary History, ed. Marc Stein (New York University Press, 2019)

- THE LAST SLIDE: “Born This Way” lyrics and song by Lady Gaga

(Streamline Label)

|

|