Black Bear Solstice Reunion 1987

By Don Monkerud

Greyish blue folds of mountains recede into the distance, one

atop the next, like waves in the ocean, wisps of light fog still

clinging to the early morning peaks. The slopes are covered with

evergreen forest and distant slashes of dirt mark roads which

wind their way between the bare earth of clearcut logging blocks,

along river highways and cut knife-like up jagged mountain

ridges.

At a lookout point on a ridge, the mountains make me feel on

top of the world; a world that stretches below me and offers a

maze of peaks and ridges requiring a map to sort out the jig-saw

puzzle of wilderness names like Grasshopper Ridge, Haypress

Meadows, Chimney Rock and Bear Valley.

My journey into the depths of the mountains has just begun.

I'm returning to a place where, almost 20 years ago, a collection

of hippies, draft dodgers, old beatniks, anarchist, drop outs and

space cadets moved into a mountain commune. They sought to escape

the Haight Ashbury in San Francisco, the draft and the Vietnam

War, overbearing parents and a culture many of them considered

corrupt and hypocritical. Over fifty adults and children

collected money from welfare checks, inheritances, savings, and

extortion from rock bands to buy 80 acres surrounded by national

forest, four hours away from electricity and the nearest

hospital. The locals claimed they wouldn't last the winter and,

if it hadn't been for dope runs to San Francisco, hikes through

the snow to replenish the tobacco supply and their dedication to

creating what they called "a new culture," they

wouldn't have lasted.

But they did survive the winters at what is called "the

Ranch." Although many have returned to the city or moved

nearby to integrate with the local towns, the place continues to

survive. On solstice over two hundred people will celebrate the

creation of a land trust which will pass the ownership from an

individual to legal collective ownership. The land will be

protected from lawsuits, the children who grew up there will be

added as owners and, hopefully, the Ranch will continue to

provide space for people living outside the mainstream of

corporate America.

A one lane twisting road hugs the granite cliffs on one side, the

other drops off to a boulder strewn river. The firs and pines

wave at me like children playing across the mountain ridges and,

when they hear the car, deer slow, perk their ears and plunge off

the embankment.

On the way into the Ranch I pass the richest hard rock mine

in Northern California which gave Black Bear its name when

established in l860. By l869 over 300 miners -- some with

families -- lived and worked here but now, only sounds of the

creek greet me as I park among the trees and walk down to the

mainhouse. Hidden behind apple trees and surrounded by a six foot

high wooden fence, the mainhouse yard is filled with tall green

grass, barking dogs and children playing hide-and-seek. A lone

hawk catches an updraft and hangs motionless above the old

schoolhouse down by the junkyard.

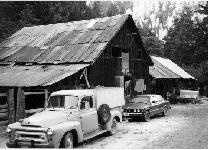

Directly across the dusty road looms the barn, its post and

beam framework held together by pegs and the weathered siding

fastened with handmade iron nails. A vast patchwork of salvaged

tin covers the roof and one skeleton-like corner hangs,

unsupported, above a crumbling rock foundation. A light shines

from the doorway and goats bleat while being milked. In the barn

loft the first baby boy, Shem, was born 19 years ago. Thirty

people packed into the loft, smoking dope, stoking the woodstove,

laughing, and singing songs during the birth. Some twenty babies

were born here and all but one, three months premature, lived.

Many of those kids will return and I'm anxious to meet them

again.

Sounds of drums echo across the valley and, inside the house,

electric lights illuminate the room. Today, a pelton wheel runs

an alternator to produce 12 volt electricity, a vast improvement

over the kerosene lamps we formerly used. The original floorplan

had many small bedrooms where rumors claim the owner of the

goldmine, John Daggett, virtually imprisoned his daughters when

he rode off to Sacramento on state business while he was Lt.

Governor of California. Now one spacious room, the roof supported

by a madrone trunk, contains several dozen people.

In the front room, a figure in a black hat plays the piano

and small knots of people laugh and talk, renewing old

friendships and greeting people they haven't seen in years. A

table filled with food sits to one side holding a heaping basket

of whole wheat bread sticks, a ten gallon bowl of salad and

army-sized trays of apricot cobbler. In the back room, along one

wall of the kitchen, stainless steel sinks are kept busy with

people washing dishes, brushing their teeth or filling tea

kettles. Like when I lived here, several 5 gallon buckets of

garbage just below the sink are overflowing.

Tom, who lives in Seattle, greets me with a hug, pushes his

glasses back and talks of the trips he has made to Nicaragua to

improve the utilities. "We've cut the average blackouts in

the electrical system from six hours a day down to two," he

says, placing his arm around his girlfriend and taking a swig of

beer. "But you heard about the American being killed down

there? We worked with him. I've reevaluating whether I'm going to

continue working there. I've been doing this so many years."

Tom turns to another acquaintance and I greet Brian, who has

come from Fort Worth, Texas. His upper body is husky although he

admits to growing pain from transporting his polio crippled legs

on crutches. He pushes a Greek sailor's hat back on his head and

smiles as he explains his research to build exact scale models of

Civil War battleships on the Mississippi.

The mainhouse was always a place where the most intimate and

deep conversation occurred instantaneously. In the old days, I often

went from one intense discussion to the next, each lasting

minutes or hours. The subjects ranged from self-doubts to

jealousy, from falling in love to the collective issue of the

moment: the kids' collective; a food run to the city; the women's

house; or whether to kill a goat for dinner. During periods when

we worked on collective projects like digging new irrigation

ditches or terracing new gardens, we missed "getting in

touch with our feelings;" when we concentrated on our

feelings, we complained about lacking collective energy to begin

new work projects. The precarious balance between what some

called the emotional sink of feeling and our workaholic heritage

see-sawed with the seasons, the amount of food in the larder and

some claimed, the phases of the moon. Tonight some of the same

intensity remains but we have matured; by 11 P.M. the house is

almost deserted.

At breakfast the next morning, 30 coffee addicts crowd around the

10 foot long cookstove, carefully watching coffee drip into pots

and performing individualized coffee rituals. In the past people

smoked dope but it's clear this morning; the main drug abuse

today is coffee. Even the teenage boys, are loading the espresso machines and the dark, thick aroma of coffee permeates the air.

On the table in the living room, homemade granola, yogurt,

bananas, oranges, whole wheat bread and oatmeal fill the table.

Everyone drinks cup after cup of coffee, the supply never

adequate to keep up with demand.

New arrivals sign in at a table in front of the mainhouse and

transfer interests in the Ranch to the Black Bear Family Trust.

Fifty "settlors," who had a collective obligation for

the purchase and maintenance of the land, are signing over their

ownership rights to the trust. According to the legal document,

the trust will perpetuate the forest community to preserve the

water, soil, wildlife and forest resources in ecological balance.

A list of "beneficiaries" may visit or reside at the

Ranch according to rules established by the collective. A board

of trustees, consisting of six past and present residents, will

manage the property and the beneficiaries will vote on important

issues. Votes to change the rules can be called by ten percent

petition of the beneficiaries. The trust will last for 60 years.

The Ranch has always been a loose affiliation, more or less

sharing a common outlook and purpose, but never following a

leader or a particular creed. We used to joke that at any given

time you could ask people why they lived here and you would get

as many answers as people, most of them having to do with living

collectively in the wilderness, being self-sufficient and

rejecting the "rat race." Now only a dozen residents

remain, living much the same way we did back then.

After meeting to plan ceremonies for Saturday night and

Sunday morning to formally transfer the land, I volunteer with

Doug, who runs his own forestry outfit out of Eugene, Oregon,

and Gail, who is now a CPA, to build a portal for the evening's

procession to pass through. Doug and I walk up the road to find

Gail and Peter, who runs a custom cabinet making shop in San

Francisco, cutting alder poles in the creek. We carry the poles

up the road, use bailing wire and nails to erect tripods and hang

the jawbone of an ass, deer antlers and a bundle of mullen from

the cross piece. Peter grabs a ladder to climb the precariously

balanced tripod and the three of us yell that he'll break his

neck. He ignores us and magically drives nails without toppling

the whole structure.

"Things are just like they always were," he

comments after climbing down. "Everybody tells you what to

do and you just have to ignore them and do what it takes to get

the job done."

We return to the mainhouse to a lunch of three kinds of

cheeses, cases of avocados, mounds of whole wheat bread, huge

bowls of potato salad and a 25 gallon crock of marinated bean

salad. The food anxieties we experienced when we lived here are

gone; then you feared that if you missed a meal no one would save

you any food and there wouldn't be enough to go around. Food runs

were vital links between the city and the Ranch and had to be

made regularly to replenish 55 gallon barrels of oil, 60 pound

tins of honey and 100 pound sacks of wheat, rice, beans and

powdered milk. Now there's more than enough food for everyone.

After lunch I talk to some of the kids who were born here and are

now young adults who are the same ages we were when we first came

to the Ranch. Laura is a junior in political science at UC Santa

Barbara and will intern for a congressman in Washington this

summer. Yoni has a new baby and manages a boutique in Yreka. Shem

is working part-time in a health spa and attending S.F. State

studying philosophy. Many of the kids still visit the Ranch every

summer, continue their friendships and several of them arrived

early to organize the weekend festivities.

The kids are different than we were: we rejected material

success, they embrace it; we rejected our parents and their

values, they accept us. We isolated ourselves in the woods; they

are able to freely move back and forth. Although we didn't create

an isolated culture, separate from the rest of society like the

Amish, we did isolate the children in the wilderness during their

formative years. Yet today, they have open and accepting

attitudes, cosmopolitan outlooks and close communal bonds. We

always claimed the future belonged to our children and now we see

the truth of that statement.

We walk to the meadow where small children splash in the

shallow end of the pond and a sweat lodge releases a thin column

of wood smoke. On ceremonial occasions in the past, like solstice

and equinox, 40 to 80 of us took steam baths in a plastic covered

pole dome next to the creek. Now a new Indian-style sweat lodge

has been constructed; a trench was dug into the ground, a barrel

stove placed in one end and the top covered with earth.

Crawling through the narrow opening, I immediately feel

claustrophobic and break out in a profuse sweat. Darkness erases

all reference points and the hot air stings my lungs. Allegra, a

4 year old Black Bear native, makes up melodious songs which she

calls angel's songs and several women sing peaceful and

comforting chants.

Incense cedar boughs are placed on the floor for their scent.

We rub cornmeal over each other and this becomes a religious

experience; the heat, the chanting, the sweating and the darkness

conspire to strip all visual stimulation; the darkness becomes a

world of spirits. Slowly I feel cleansed as the city food, air

and stress rolls off me in sweat to drip into the earth.

Star sits next to me in the darkness and says a man's

presence is unusual for she lives in a women's world; her social

activities are with women; her friends are women; she has nothing

to do with men. "People used to be threatened by us, but

that antagonism is gone now. I guess we've made some progress in

the past 15 years."

Star explains that women had held "healing sweats"

for years; women gather to heal each other by singing songs,

talking in groups and meditating on those who are ill or need

strength. Earlier in the day, the women gathered on the knoll and

everyone spoke: remembering people who weren't there; stating the

significance of the solstice and the trust; accepting the death

of Meredith, who is dying of bone cancer in San Francisco;

recalling past events; and projecting a fulfilling future. She

says the women have a collective strength and support each

other's personal development.

Before the women asserted themselves, the Ranch, copying the

larger society, was male-dominated. By holding women's meetings,

forming a women's house and taking leadership roles, Ranch women

established their independence. At first, they worked on trucks,

handled rifles and wielded chainsaws. People sought their own

level of activity based upon preference and ability, not sex. The

results can be seen today at the Ranch. Men are cooking and

caring for the children, women hold full-time jobs and, while

conflict remains, the old stereotypes are gone.

At 11 o'clock that night, we began the solstice ceremony by

following a heavy wooden totem and dozens of candles in cans

called "Salmon River bugs." Strung out on the road like

fireflies, the soft haloes of light bounced across the road and

into the dark forest. We walked beneath a cold, clear sky, the

forest towering above us, an owl hooting in the distance. At

selected intervals we stopped, bindles or hobo bundles were

unrolled and various objects were revealed to tell stories from

Black Bear's history.

Efrem and Jeff's bundle held a plastic bag of herbs,

resembling marijuana, to recount the first spring when the

Siskiyou County sheriff busted the Ranch for dope. Jeff told of

awakening one morning l9 years ago when John tossed a joint out

the window directly in front of a sheriff's deputy. After days in

jail, Jeff appeared in court handcuffed to thirty other hippies

busted around the county and was released due to insufficient

evidence. The sheriff posed for the local newspaper holding

evidence from the raid, a tomato plant.

Further down the road we stopped at a meadow which we had

terraced by painstakingly shoveling top soil into a pile,

leveling the subsoil and redepositing the topsoil into a bed like

we read they did in the revolutionary village of Lou Ling in

China. Osha rolled on the ground, clutching his stomach and

groaning. Michael ran to him, promised to cure him with herbs and

stuffed grass into his mouth. Osha continued to wither on the

ground until Owlin, a medical doctor, gave him penicillin. Owlin

claimed Michael was a quack and Michael pronounced Owlin a

technician without feelings. But then Owlin became sick and

Michael fed him herbs. Such is the stuff of legends.

On the knoll we gathered before a huge crackling bonfire,

much differently than we would have 20 years ago. Then we gorged

ourselves on roasted goat, drank homemade wine, smoked dope and

ran off with someone else's mate. Tonight such behavior would

precipitate a crisis. We listen to a '60's poem by Mary praising

the wonder of free sex which, with the threat of aids, may be

gone forever. Several songs were sung and poems recited, setting

the stage for the following day. By 10 A.M. the next morning,

everyone had gathered around a new bonfire on the knoll and

children carried boughs of burning incense cedar around the

circle to let the smoke waft over each person in a purification

ritual. Geba blew a greeting to the six directions with a small

reed flute and read an Indian poem reminding us that we cannot

own the land; the owls, the coyotes and the wild things own the

land. Statements of purpose from the trust were read. Efrem read

a manifesto from the first winter at the Ranch; the "Get

With It Party" rejected society's rules and promised to

create a "new culture." Michael talked about sacred

herbs, sprinkled some into the fire and we formed a circle and

clasped hands.

When we returned to the fire the six new trustees sat on a

log next to the fire and people in the circle rose to give

counsel on preserving the Ranch. Jeff wanted to preserve the

ecology and sacredness of this special place, Sala wanted to use

the Ranch for healing seminars and several voiced a desire to

provide a place for Central American refugees. The historic sites

should be preserved and the trees should never be clearcut.

Leslie rose to claim the 60's should not be forgotten and the

spirit which originally brought us here should be continued. If

we were serious about ecology and preservation, Carol said,

restrict the goats which have destroyed the native vegetation.

Clarence claimed if the goats were gone, all the vegetation would

return in a year. Deed suggested the real specialness of this

place was not the physical land but the people, the current and

past friendships and our collective energy which should be

maintained when we returned to the city. Again we rose to hold

hands in a huge circle.

Richard, in whose name the land was registered for l9 years,

paced the fire circle . "So the truth is out, some of you

knew and some of you didn't," he said. "I never owned

the land, I only held it in my name for all of you." He read

a poem Lew Welch wrote when he lived on the Salmon River in l962,

entitled "He prepares to take leave of his hut,"

concluding with the lines,

"Why should it be so hard to give up seeking something

you know you can't possess? Who ever said it was easy?"

The documents have been signed and the Black Bear Family

Trust is now officially the owner of the Ranch. In conclusion,

each person had collected some token which represented the Ranch

and we circled the fire dropping herbs, pine cones, special

rocks, sticks from the old Salmon smoker, and walnuts from the

tree at the mainhouse backdoor into a large bowl. Carol deposited

a huge iron screw, Missy a goat turd and Martine an old bent

clock face. After lunch, most people would be leaving for their

homes and work the next day.

So what has changed in twenty years? Most of us have turned

grey, gotten heavier around the middle, given up drugs and

settled down. Some live nearby; their hair remains long, they

live in the country and eke out a living working in the woods and

growing vegetables. They are involved in struggles against the

CIA's Contras, clear cutting and herbicide spraying. Others have

moved away and now work as nurses, scientists, businessmen,

building contractors, teachers, midwives and lawyers. The

majority continue to hold egalitarian, anti-war and ecological

political attitudes, deal with others in a real and humane way

and continue Ranch friendships.

But in many ways the Ranch has not changed. The physical

place, although cleaner and more tidy than when 80 of us lived

here, hasn't changed in over a 100 years. The mainhouse garden

has benefited from 20 years of mulch and compost and the

irrigation systems still works. There is no money or time economy

here and basic survival continues as it always did; feeding and

milking the goats, gathering firewood, preparing meals from basic

ingredients, planting and harvesting the gardens, and

entertaining each other.

With the creation of the trust and the land paid for, the

question of what will happen in the next sixty years passes to

our children. Will the land trust alter the human ecology? Will

new people move here to follow the same vision we had twenty

years ago? Will the survivors sell the Ranch in sixty years and

go their separate ways? How long can the Ranch continue as a semi-subsistence, agricultural and ecological community?

the end

|

|