The Genesis of NOWSREAL, a film about the San

Francisco Diggers

[Ed. note: it is with deep appreciation that we publish Kelly Hart's

account of the making of Nowsreal in September 2018, exactly fifty years

after the events he describes here. For so long, the genesis of

Nowsreal

was a mystery just as much of the Digger mythos remains mysterious. Now, Kelly has

pulled back that curtain to show us what the film makers were

thinking when they created this unique and important historical

document.]

One peaceful evening when I was living in a small cabin nestled at

the base of some giant redwoods near Monte Rio, along the Russian River

in Sonoma County, California, I heard a deep rumbling sound approaching

up the driveway. I looked out to see what was causing the commotion, and

soon encountered a leather jacketed man riding a Harley Davidson

motorcycle. It turned out to be Billy Fritch, also known as Sweet

William, and he was on a mission from the San Francisco Diggers. He had

been sent to enlist my help in making a movie about the Digger movement.

Evidently, they had already started with the project, but the cameraman

suddenly abandoned them and they were desperate to find a replacement.

I was a budding young filmmaker at the time, in my early twenties,

and trying to establish myself. Up until that time I had completed very

few projects and was thirsty to get some real experience under my belt.

I told Billy that I would think about it and get back to them. He was

satisfied with that and rumbled on down the dark driveway, leaving me to

ponder the situation.

The San Francisco Diggers were not your ordinary organization; in

fact there was very little about them that was organized. They were more

like a collective of radical individuals who wanted to stir up society

and make some drastic changes with how people thought about life and how

it was conducted. This was at the height of the psychedelic revolution

in the late 1960’s and everything was on the table, as far as the

Diggers were concerned.

I decided to go for it, and contacted Peter Berg, one of the central

characters involved with the film concept. I met with him in San

Francisco and he explained that so far they only had a few minutes of

16mm film shot, but had ideas for much more than that. They didn’t

really have a script to work from; what they had were a stack of index

cards with scenes written on them, representing the primary activities

or situations that were emblematic of what the Diggers were about. These

cards were generated in brainstorming sessions involving some of the

luminaries of the Digger movement: along with Peter Berg and Billy

Fritch, was Emmett Grogan, Peter Coyote, Judy Goldhaft, Ron Thelin, and

Lenore Kandel. Many of these folks had been part of the San Francisco

Mime Troupe, and were predisposed to acts of street theater as a mode

for engaging the public in thought-provoking stunts.

The concept for the film was that it would be a sort of patch-work

montage that would of its own force describe what the Diggers were

about. There was to be no narration, or “internal monologue,” as Peter

Berg described it. It was to be a kind of stream-of-consciousness film

that audiences could experience directly, without having to be told how

to perceive it. This approach appealed to my own emerging ideas of how

films could be made, so I embraced the challenge.

I offered to make myself available during the summer of 1968 to run

with the Diggers and document their activities. Whenever something was

happening that folks thought should be part of the film, they would

contact me and I would arrive with my 16mm camera. This was a simple

little Bolex with no sound syncing capability, so what I captured was

just visual. Often Peter Berg would carry an audio tape recorder and

capture sounds that might be useful.

As was central to the Digger philosophy, NOWSREAL was to be available

only for free, and in fact there was basically no budget for the film.

We relied on donations of “end rolls,” the bits of film left over after

professional film crews approached the end of their rolls of raw film. I

would load these onto small reels that fit in my Bolex and expose them

for later development. Somehow we managed to get by on the largesse of

others interested in seeing the success of our enterprise. One such

person was Haskell Wexler, the Hollywood cinematographer, producer and

director, who I later learned was one of the early cameramen involved in

the NOWSREAL project.

By the time that summer had past and we had captured a good

representation of Digger activity, many of the principal actors had

dispersed, including Emmett Grogan and Peter Coyote, leaving Peter Berg

and myself to carry on with finishing the process of making the film.

This is probably just as well, since it takes real concentration and

focused effort to edit a film, and is better done with just a few minds

involved. I had rudimentary 16mm editing equipment set up in my Monte

Rio Cabin, so that is where Peter and I would get together and play with

and assemble the patch-work that was to become NOWSREAL.

Peter brought with him the bag of audio tape he had acquired so we

could use that to fit audio with visual components. There was little

opportunity to try to match these to the extent of creating true lip

synced scenes, but we did attempt this on a few occasions. I remember

having to retard the rate of audio some to get it to match the film.

I feel that the creation of NOWSREAL was one of my most successful

creative collaborations in my limited film career. Peter and I worked

well together, with neither of us dominating the flow of the editing

choices. One of us would suggest trying something, and we would see

whether it worked or not. As the film evolved it seemed to have a mind

of its own, and grew almost organically. I suppose that you could say

that Peter assumed more the role of director and I was more of the

editor, in that Peter was really one of the Diggers, and I was more of

an outsider looking into their world, so Peter had more at stake in the

result.

In keeping with our frugal approach to filmmaking, I had made a

device for doing some basic processing of raw film (I had many years of

experience as a still photographer developing my own negatives.) I had

even made a simple 16mm film printer using parts from an old movie

projector, and I used this to create some of the black and white scenes

of people dancing with an odd “solarized” look.

By the time that we were approaching the end of the project, I had

moved to a rented house in Emeryville, closer to San Francisco, making

it somewhat easier with the logistics of editing. What we had at that

point was an edited workprint and still needed to assemble the original

reversal film in an A/B roll configuration, complete with a separate

16mm audio track, in preparation for striking prints that could be

projected as usual. All of this takes money, which was in short supply.

Haskell Wexler, our savior, came to the rescue and offered to take over

the printing of the film through his professional lab account in Los

Angeles. Peter and I flew to LA at one point to meet with Haskell and

make all of the arrangements. To this day the original A/B rolls are

still in a vault somewhere in Los Angeles.

Now that we had a few prints of the film that could be shown, we

looked for appropriate venues for doing this. The fact that the film was

specifically made to only be shown for free, actually hampered this

effort, because few conventional movie theaters were interesting in

showing films for free. As a consequence, NOWSREAL was projected at

night on the walls of buildings in San Francisco, at parties or

gatherings or in the odd coffee house or bar. I organized showings at

places like libraries or film festivals, but overall, NOWSREAL has

gotten very little exposure.

Over the years, some scenes have been excerpted for inclusion in

other historical documentary films, so NOWSREAL has gained a certain

archival value. Currently it is available for viewing on the Diggers

archival website:

www.diggers.org/nowsreal.htm.

|

Rosana & Kelly Hart

|

A Filmic Odyssey with NOWSREAL

The first time I saw NOWSREAL was at one of the collating

parties that Peter and Judy Berg held in their home in San Francisco's

outer Noe Valley neighborhood after they had started Planet Drum. This

was when Planet Drum was a periodic bundle of printed communiqués sent

in from far-flung correspondents to the central burgeoning bioregional

network that the Bergs would compile and send back out in odd-sized

envelopes always with the iconic Sami shaman figure printed on the

outside of the bundle. Later, Planet Drum would become a Foundation and

Office with an agenda of projects that (to this day) informs the

bioregional movement—itself partly an offshoot of the Digger movement

that first coalesced around the daily Free Feeds in the Panhandle—that

10-block long green strip that played a similar role that public commons

have traditionally provided in the formation of underground and

alternative cultures throughout history.

Over the years, numerous opportunities arose for the showing of the

"digger film". When Samurai Bob got back to San Francisco in 1976 with

Jane Quattlander, they would borrow Peter and Judy's copy (the only one

in existence) and show it on Haight Street at the Red Victorian, that

little cinema where the only seating was a series of deep cushion

couches, more like an intimate bedroom than a movie house. Or they would

take it to one of the anti-nuclear events to raise awareness of the

dangers of Diablo Canyon or Vallecitos or any of the other nuclear

facilities in California, including Livermore Labs where the latest

nuclear weapons were developed. Somehow, the showing of Nowsreal

was a catharsis from the frightening idea of nuclear annihilation.

Inevitably at these events, the increasingly brittle film would break

in the middle of the showing. Bob would carefully splice the two ends

(cutting off a small piece on either side) and tape the whole back

together. Slowly over many showings, cherished scenes from Nowsreal

were disappearing from historical view. In 1978, after coming into a

small windfall of cash, I called Peter and suggested that I would like

to fund the printing of a brand new copy of Nowsreal if such a

thing were possible. For some years, Peter had called me "digger

archivist" so he approved the idea wholeheartedly. I made arrangements

with the Hollywood producer who kept the original positive print in his

vault to have a 16-mm copy made.

Within a few months, the call came to bring this new copy of

Nowsreal out of the darkness and into the light. Country Joe

McDonald was planning a film festival on the Cal campus in Berkeley. He

had contacted Peter Berg who contacted me to see if I would take the new

(complete) 16-mm print to have it shown at Wheeler Auditorium. I'll

never forget the event which was one of those moments that the Universe

throws each of our ways to keep changing perspectives. The audience was

a young Berkeley crowd and all that implies in terms of diverse and

vocal frames of reference. This was 1979, barely more than a decade

since the events that Nowsreal depicted. Up to this time, all the

Nowsreal showings I'd attended had been mostly counterculture

crowds. I knew I wasn’t on Haight Street any longer when a slow hissing

started in the audience during the scene at the Straight Theater where

the camera focuses at certain points on the women dressing and

undressing for their exercise class. The biggest reaction was during the

scene at a remote garbage dump when some of the men on their motorcycles

go for gun practice and chop talk. A sizeable chunk of the Berkeley

crowd got up and left the theater at this point. That was the last time

I brought the print out to show.

Fortunately the invention of VHS and the introduction of the first

commercial VCR by the Japanese corporation JVC in 1976 would solve the

problem of scarcity of an archival resource. In the early 1980s Peter

Berg introduced me to Kelly Hart, the filmmaker who had done the camera

work and editing of Nowsreal. Kelly had gotten a call from a

British film group working on a film retrospective of the Sgt.

Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band album. The film would be released

on June 1, 1987, two decades after the original release of the Beatles

album. The title of the film, “It Was Twenty

Years Ago Today,” referred to one of the lines from the album’s

title cut, as well as the planned release of the film. The British

producers wanted to look at Nowsreal to see if there was footage

they could use (it turned out there wasn’t.) Since I had this virgin

(nearly) copy of Nowsreal, it was arranged that I would take it

to Diner Studios in San Francisco where the producers would pay to have

VHS master copies made, one for Kelly, one for them, and one for the

Digger archive. It’s that VHS master copy from which myriad number of

copies were made. At one point, as part of the ongoing effort of the

Digger Archive to re-release Digger texts, we made several dozen copies

of the VHS tape (with specially designed cover graphic) and distributed

them by hand at solstice and equinox celebrations. Samurai Bob would

have been proud of the effort his enthusiasm had spawned.

Then came the Internet. In 1991, I saw a demonstration of the World

Wide Web by Tim Berners-Lee, the inventor of HTML, at a professional

conference I was attending. When I got home, the first thing I did was

to start working on a web page for the Digger Archives. At that point

there were maybe a hundred web sites in the world. The idea behind the

online archive was to provide access to rare materials to inform and

inspire a generation who had never known the Diggers. That’s still its

main purpose. Finally after many false starts trying to get Nowsreal

converted into web format, it’s done. The quality is not as good as it

could be (in my perfectionist's estimation.) This is after all a fourth generation copy of the original.

Perhaps someday I'll figure out a better way.

—epn 2014-08-13 |

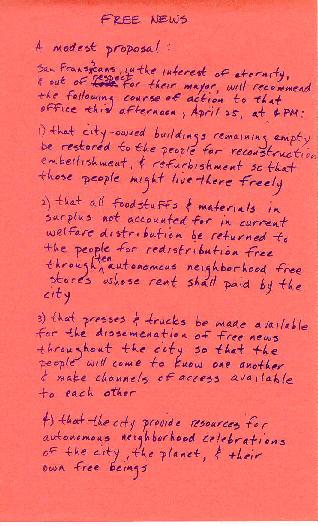

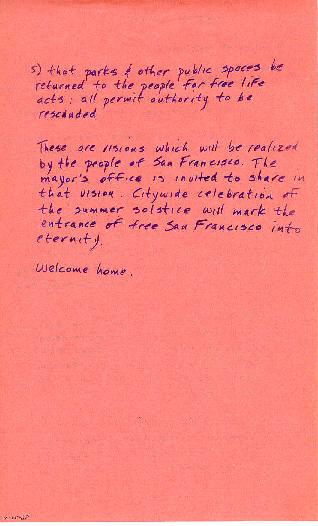

Text of the Free City proclamation depicted in Nowsreal on the

steps of San Francisco City Hall, Apr 25 1968.

|