The Story of God’s Eye Bakery

The Diggers at Resurrection City (Memories Passed on to Me)

By Ángel L. Martínez

Contents

In the "official" Digger chronology, the

temporary autonomous installation at Resurrection City in May and June,

1968, known as God's Eye Bakery, is the third such Digger

free bakery.

Walt Reynolds, the

electrical engineer who taught the Diggers to bake whole wheat bread at

All Saints' Church in San Francisco, took his bread baking skills to

Washington, DC, to set up the God's Eye Bakery. One of the many

activists who occupied the National Mall during the six-week period in

which Resurrection City existed was Carlos Raúl Dufflar. His son, Ángel

Martinez, grew up listening to his father's stories of 1968. Now, after

discovering the Digger web page with the history of the Free Bakery

movement, Ángel has written the following account for the historical

record. All we can say is muchas gracias, Ángel. And continue on with

your obvious talent of capturing history in written accounts of the

past.—ed.

In Spring 2020, Carlos Raúl

Dufflar and I gave a presentation on the history of the original Poor

People’s Campaign (PPC) and his experience in the encampment it

established known as Resurrection City. By this time, it had been a

series of several he had been doing since the 45th PPC Anniversary March

from Baltimore to Washington, tracing the Route 1 of the Northern

Caravan that brought Dufflar to the City in May 1968.

Five decades later, he was specially invited to tell the stories that he

had told me through the years. Each time he was the original PPC’s live

testament to the power of organizing, I was recalling as much as I could

devour, besides hours of stories personally told to me. Now, it was

going to be different, and not just because this took place soon after

the plague had moved our gathering online.

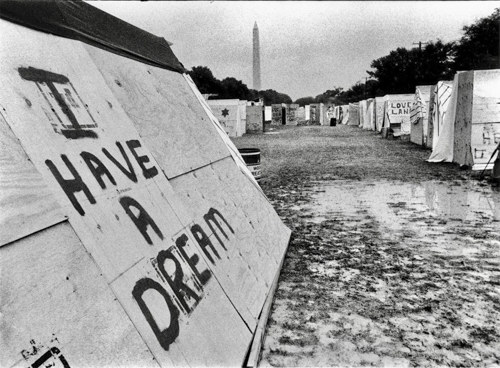

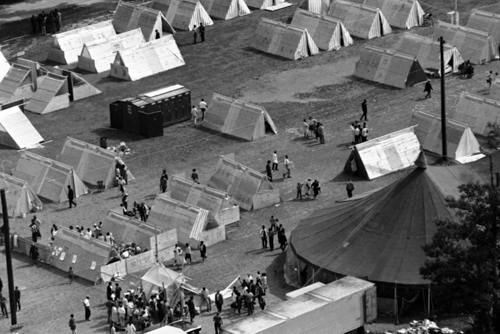

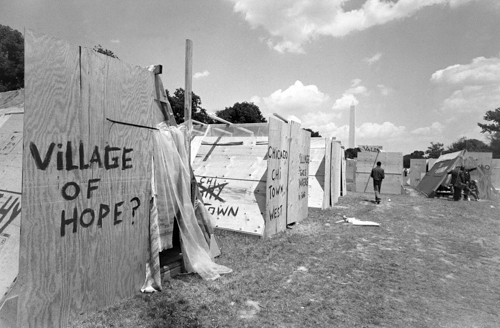

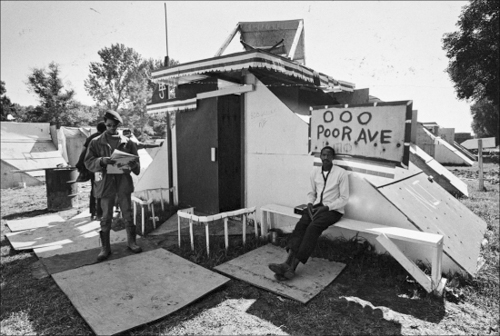

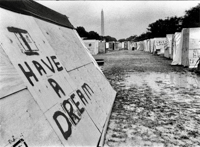

Resurrection City, in West Potomac Park on the National Mall of

Washington, DC, was at the center of the story we told. It was, as I

have understood it, a community as well as an expression of political

and cultural solidarity born on Mother’s Day, 1968. This City scared

Congress, the White House, law enforcement, and corporate interests.

Very early on the morning June 23, 1968, the residents were evicted with

tear gas, bullets, other extreme violence, and mass arrests (over 370)

by the FBI, US Army, military intelligence, DC National Guard, and DC

Metropolitan Police. Many of the arrested were not released until July.

To understand the depths of the government’s fears, especially in stark

contrast to today, 20,000 Guard troops were ready to invade if they were

to rebel.

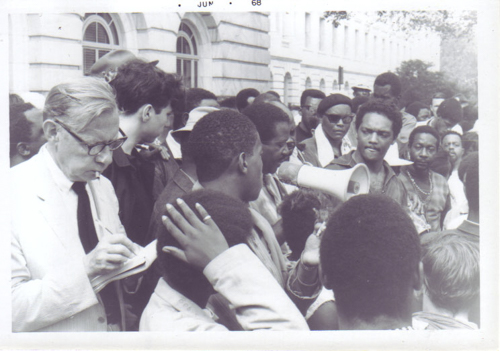

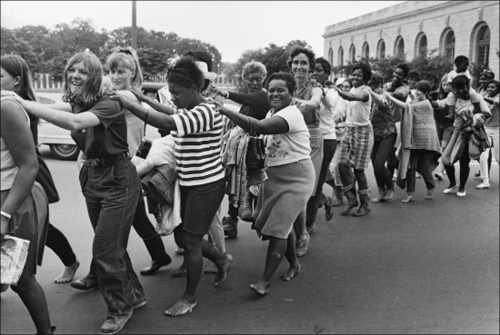

As the City thrived, it attracted solidarity and support from

innumerable organizations and movements. (To be certain, while it

attracted religious groups that offered aid, the encampment hardly had

any religious over [or under] tones that its name would have implied.)

The Diggers were among the groups to answer the solidarity call.

At one point in our presentation, he had to step away from the screen.

It was Q&A time and a question did emerge in that moment which I was

confident enough to answer. It was my turn to talk about in particular

about an amazing story that I have been told for years: the solidarity

work of the Diggers at Resurrection City.

As I was telling the story, my response was smooth flowing because one

of his most cherished memories of Resurrection City was the Diggers’

contribution to the city — God’s Eye Bakery — which was what we would

call a central kitchen. The Bakery is a story I can never hear often

enough, and has been told me enough times for me to confidently place

the bakery at the center of life at the City.

Besides him, I had only heard about the Diggers in the documentary

Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band 20th Anniversary in 1988. The belief in everything people needed being provided for free

was a principle that meshed well with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s final

struggle. In fact, the ethic certainly embodied that hope in the City.

The difference was that he was a witness to the work of the Diggers.

Just as visceral as a symbol of Resurrection City as the sturdy,

distinctive A-frame houses was bread baked fresh in coffee cans. (The cans, to remind

younger audiences, were enormous compared to those commonly seen today,

meaning more food to pass on the community.) To hear Dufflar tell it,

God’s Eye Bakery was highly instrumental in the everyday life of the

community. There was always a line each morning to receive a loaf. The

warm bread provided every morning remains at the center of the memories

as much as the houses and the seemingly endless rain.

Dufflar’s memories of his time there are, I have found, incomplete

without giving a shout-out to the Diggers and God’s Eye Bakery. In fact,

much of what I know about the Diggers comes from what he has related to

me. He vividly remembers the bakery’s house, on which was painted,

“BREAD — FREE FOREVER — GIVE US THIS DAY” with a coffee can bread image

superimposed on it, and its picture preserved on The Digger Archives

only adds to his warm memories. He is one more witness to what Walt

Reynolds and his compas did for the City.

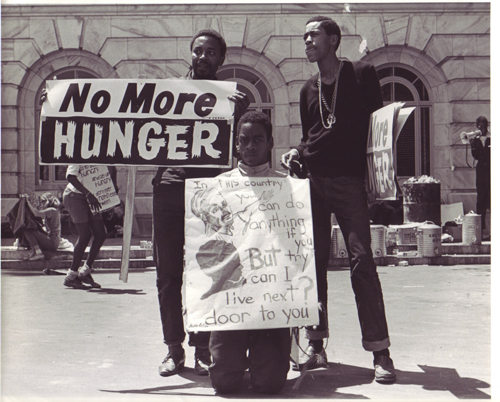

Above all, God’s Eye Bakery was more than just a people’s kitchen in

that sense. The work they performed went much deeper. Poverty, in the

economic sense, had many profound effects then that drove the creation

of the original PPC. It is true even more now. What God’s Eye Bakery

gave was more than just a staple food; the bread was a sign of major

change in people’s lives. In Resurrection City, the solidarity aid and

assistance were at the least life-improving, if not life-saving. As

Dufflar told me, this was the first time that many of the City’s 5000

residents had ever eaten whole-wheat bread, let alone freshly made, let

alone right out of coffee cans. The Bakery generated much enthusiasm in

the encampment, again as Dufflar told me. Each day, residents either

took home a loaf or had slices of it with butter, peanut butter, and/or

jelly. No wonder, then, Dufflar said, “Everybody dug the Diggers!”

Daniel Cobb, writing on the Indigenous presence at Resurrection City,

placed the bakery at the center of the story, too:

They visited often for planning sessions, rounds of freedom songs

that “shook the heavens,” and social gatherings, or they would meet

simply to eat hot, fresh coffee-can bread at God’s Eye Bakery.

(Cobb, 176)

I could imagine those cylindrical loaves warming the spirit as well

as the body. That is the power the Diggers had. The loaves showed why

the Diggers and God’s Eye Bakery matter in the memory of Resurrection

City. "From the bottom of my heart," Dufflar to this day offers thanks.

Sources:

Daniel M. Cobb. Native Activism in Cold War America: The Struggle

for Sovereignty. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2008.

See "Third Free

Bakery (Resurrection City, 1968)" for an article from the Berkeley

Barb (June 14, 1968).

Links to Poor People's Campaign References

Historical 1968 Movement

Wikipedia page on

Poor

People's Campaign (1968)

Current Groups (2021)

Poor People’s Economic

Human Rights Campaign

Poor People’s Embassy —

Embajada de la Gente Pobre

Poor People's Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival

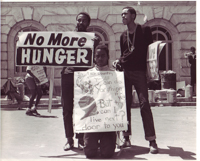

Photos:

Images borrowed from Wikipedia and Google Image Search.—ed.

|

Images are clickable

|