Winstanley & The Diggers

Excerpt from Communalism: From Its Origins to the Twentieth Century

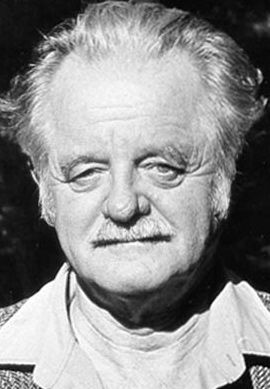

By Kenneth Rexroth

Surprisingly the seventeenth century with its almost continuous wars of

religion was not a good time for the radical Reformation. Cujis regio,

ejus religio — religion had become a matter of large-scale

politics. Wars fought between nations and alliances of nations divided

Europe into blocks of Catholics, Lutherans, and Calvinists. Small groups

of the elect were crushed out by the sheer weight of the contending

monsters. Then, too, the Thirty Years War, which was fought to destroy the

Holy Roman Empire as the dominant power in Europe, also crushed or

profoundly distorted the culture of the various parts of the empire.

Germany emerged fragmented and wasted and did not recover for generations.

The radical Reformation had been a natural outgrowth of the culture of the

late medieval middle of Europe and the Thirty Years War destroyed its

roots. In the Netherlands, Switzerland, and amongst the Hutterites in

their remote refuges, a process of fossilization had set in.

The English Civil War and commonwealth were essentially a product of

class struggle, and the proliferation of sects in the latter days of the

Civil War took place almost entirely in a lower middle class and upper

working class context. In spite of their name, the Levellers were far from

being unbridled democrats. They proposed to extend participation in power

only to men of substance — small, middle-class substance — like

themselves. The Fifth Monarchy men were such extreme chiliasts as to have

no real social program.

The Ranters were only incidentally millenarians. Basically they were a

revival of the Brotherhood of the Free Spirit, who believed that once

divinized and absorbed into the Godhead the soul was incapable of evil.

Like the Adamites who were expelled from Tabor they lived exalted in an

amoral ecstasy. If they practiced community of goods, nudism, speaking

with tongues, and sexual orgies it was all part of a frantic, hurried, and

hunted life lived in a state of unrelieved excitement. Some Ranters were

simply extreme Spiritualists, descendants of Meister Eckhart and the

Rhineland mystics; and with the Restoration of Charles II they were

absorbed into the Quakers. They really lay completely outside the

development of English Puritanism.

The agitation of the Levellers lasted only three years. They were

primarily a political party who wished to see the promises of the Rump

Parliament — the recruiting propaganda for the second stage of the Civil

War — fulfilled. Their leader, John Lilburne, had been an associate of

Cromwell’s at the beginning and the Levellers were perfectly right when

they accused him of selling out. Although the final form of their Agreement

of the Free People of England, their political manifesto, proposes a

broader democracy than would come to England until the end of the

nineteenth century, they did not believe in universal franchise, but

excluded servants, paupers, farm laborers, Roman Catholics, Episcopalians,

Royalists, “heretics,” and, of course, women. Essentially they were

left-wing Calvinist republicans. By the end of 1649 they had been

completely suppressed.

In 1653 the Nominated or “Barebones” Parliament, chosen from the

leaders of the Independent Churches, sat briefly; but its attempts to

inaugurate the rule of the saints were so radical and disorganized that

Cromwell dissolved them and became dictator — “Protector.” This led

to a revolt of the more extreme millenarians, to whom Cromwell became the

“Little Horn” of the Beast of the Apocalypse. They proposed to

establish a ruthless despotism of the elect in preparation for the final

kingdom of the millennium. The Fifth Monarchy movement, lacking both

ideology and social program, sprang up through an inflamed rhetoric which

consisted exclusively of the reiteration and rearrangement of the

apocalyptic language of the Books of Daniel and Revelation. It was a

massive hysterical outburst of rage by men who knew they had been

betrayed. Unlike the Levellers, they took to armed revolt. In April 1657 a

handful of men rushed about London fighting as they went and were quickly

suppressed. In January 1661 another, even more frantic and desperate

attempt occurred, and those who were not killed in the streets were

executed, and the sect came to an end.

Movements like the old Family of Love, the Seekers, and the Quakers

grew in the interstices of the English Reformation, at first so

clandestinely that from Henry VIII to the emergence of the Quakers we know

surprisingly little about them. Various groups were accused of practicing

community of goods; but although the movement was widespread, at least in

the imagination of its persecutors, each individual group seems to have

been a tiny conventicle, with members meeting in one another's’ homes

and sharing their resources. Theologically the older Anabaptism died out

in England and was replaced by Spiritualism. The modern Baptist sect which

arose in those days was an independent development which owed practically

nothing to continental Anabaptism but was rather a special form of

Calvinism. In the writing and preaching of George Fox and the earliest

Quakers there were no special social or economic concerns, and it was only

after the Restoration with the consolidation of modern Quakerism in the

days of William Penn that the Quakers became anti-political.

A little group of unemployed laborers and landless peasants gathered at

St. George’s Hill near Walton-on-Thames in Surrey on April 1, 1649, and

began to dig up the common land and prepare for sowing vegetables. Their

leaders were William Everard and Gerrard Winstanley. At first their

activities aroused curiosity and a certain amount of sympathy but as time

went on the local lords of the manor, the gentry, aroused the populace and

the mob shut the Diggers up in the church at Walton until they were

released by a justice of the peace. Again they were captured by a mob and

locked up in the nearby town of Kingston and again released. On April 16 a

complaint was laid before the Council of State, who sent two groups of

cavalry to investigate.

The captain, Gladman, reported that the incident was trivial and sent

Everard and Winstanley to London to explain themselves to Thomas Fairfax.

They explained that since the Norman Conquest England had been under a

tyranny which was now abolished, but that now God would relieve the poor

and restore their freedom to enjoy the fruits of the earth. The two men

explained that they did not intend to interfere with private property, but

only to plant and harvest on the many wastelands of England, and to live

together holding all things in common. They were certain that their

example would be followed by the poor and dispossessed all over England,

and in the course of time all men would give up their possessions and join

them in community.

A month later Lord Fairfax stopped by on his way to London, to see for

himself what was happening, and decided it was a matter for the local

authorities. In June another mob, including some soldiers, assaulted the

Diggers and trampled their crops. Winstanley complained to Fairfax and the

soldiers were apparently ordered to leave the Diggers alone. In June the

Diggers announced that they intended to cut and sell the wood on the

common, and at this point the landlords sued for damages and trespass. The

court awarded damages of ten pounds and costs, and took the cows

Winstanley was pasturing on the common, but released them because they

were not his property.

Perhaps because of the judgment, and because their crops had all been

destroyed, the Diggers moved in the autumn to the common of Cobham Manor,

built four houses, and started a crop of winter grain. By this time there

were over fifty Diggers. When they refused to disperse, Fairfax finally

sent troops who, with the mob, destroyed two of the houses and again

trampled the fields. The Diggers persisted and by spring they had eleven

acres of growing grain and six or seven houses and similar movements had

sprung up in Northamptonshire and Kent. The landlord, a clergyman, John

Platt, turned his cattle into the young grain and led a mob in destroying

houses and driving out the Diggers and their women and children.

On April 1, 1650, Winstanley and fourteen others (Everard, who seems to

have been demented, vanishes early in the story) were indicted for

disorderly conduct, unlawful assembly, and trespass. There is no record of

the disposal of the indictment, but this was the end of the little

communist society at Cobham.

This is all there was to the Digger movement, a trivial episode which

was a ninety-day wonder in the news sheets when it first started, and

which was almost without influence at the time, and easily could have been

lost to history — except for the writings of Gerrard Winstanley. All

during the course of the experiment he issued a series of pamphlets which,

as his ideas rapidly evolved, came to constitute the first systematic

exposition of libertarian communism in English.

All the tendencies of the radical Reformation seem to flow together in

Winstanley, to be blended and secularized, and become an ideology rather

than a theology. Spiritualism, radical Unitarianism, apostolic communism,

evangelical rationalism — one could easily believe that he was well read

in the entire literature of the radical Reformation. Yet we know nothing

of his intellectual background, reading, or influences. He never quotes a

secular authority, only the Bible, in all his writings, and we know

nothing about his education, and little enough about his life. He says

again and again that his ideas owe nothing to any other man or to any

book, only to the Inner Light and to its “openings” in visionary

experiences. Perhaps that is true.

Gerrard Winstanley was born in the village of Wigan in 1609, in a

family of small gentry and merchants that had long been prominent in

England. His father Edward was registered as a mercer and the son was

raised in the cloth trade. Somewhere he must have received a fairly good

education for a provincial middle-class boy because, although he never

uses, as did everybody else in his day, a classical quotation, this very

avoidance would indicate not only that he was well educated but quite

sophisticated, and the prose style in his later pamphlets is that of a

highly literate man. At the age of twenty he was in London, apprenticed to

Sarah Gater, widow of William Gater of the Merchant Taylor’s company,

and at twenty-eight he became a freeman and went into business for

himself. Three years later he married Susan King. In the depression which

began in 1643 he went bankrupt, and he was still being sued by one of his

creditors in 1660. After his bankruptcy, he left London to stay with

friends in the neighborhood of Cobham and Walton-on-Thames in Surrey

where, to judge from his troubles over the cows, he made a living

pasturing other people’s cattle on the common.

At some time before his first publication Winstanley joined the

Baptists and may have been a preacher for them, but before 1648 he had

come to believe that baptism was only an unimportant form and had ceased

to attend Baptist conventicles. Rather he met with those little groups of

Seekers who gathered in one another’s homes and waited for the Inner

Light, and spoke only ex tempore. At this time he went through a

period of temptation, guilt, fear of death and damnation, of devils and

ghosts, and a sense of loss and abandonment, a time of spiritual crisis

universal in the lives of the great mystics. Finally, he came to an

abiding consciousness of God within himself, the assurance of universal

salvation, and the peace which comes with direct experience of mystical

illumination. His first two publications are really devoted to

assimilating this experience. They move from a highly spiritualized

chiliasm, developing a well-reasoned doctrine of universal salvation, to a

highly spiritualized philosophy of history rather than a theology.

Even in these early pamphlets Winstanley has original insights. His

chiliasm does not take the form of the salvation of a handful of the elect

but of the divinization of man. In his teachings on sin and salvation the

original sin of Adam was not lust but covetousness — selfishness and the

desire for power — in which Winstanley shows himself an incomparably

more astute moralist than the Puritans. Ultimately, the God who operates

in history, in all things, and consciously in the soul of man, is called

“Reason.” It would be a mistake to decide from this, as some modern

writers have done, that Winstanley was a precursor of eighteenth-century

rationalism. His reason is the ineffable God of Plotinus and Meister

Eckhart apprehended in the mystical experience, though not separated from

man as the Omnipotent Creator, but as the ultimately realizable in all

things. So for him the narrative of the Old Testament and the life and

passion of Christ cease to be historical documents about something that

happened in the past and become symbolic archetypes of the cosmic drama of

the struggle of good and evil that takes place in the soul of man.

When the Digger tracts began with the adventure at St. George’s Hill,

Winstanley’s basic appeal was not to the practice of the apostles or to

an eschatological ethic in preparation for apocalypse. His communism

begins with an “opening,” an actual vision, and the appeal is always

to his transcendent and imminent Reason — to a spiritualized natural

law, not unlike the Tao of Chuang Tsu.

Likewise I heard these words: “Worke together. Eat bread together.

Declare all this abroad.” Likewise I heard these words: “Whosoever

it is that labours in the earth or any person or persons that lifts up

themselves as Lords and Rulers over others and that doth not look upon

themselves equal to others in the creation, the Hand of the Lord shall

be upon the labourer. I the Lord have spoke it and I will do it. Declare

all this abroad.” [The New Law of Righteousness, 1648]

This vision came not as a command from on high, but as a voice opening

out of the experience of nature itself, for, says Winstanley, the doctrine

of an anthropomorphic deity, set over against and independent of nature,

is the doctrine of a sickly and weak spirit who hath lost his

understanding in the knowledge of the Creation and of the temper of his

own Heart and Nature and so runs into fancies. [The Law of Freedom

in a Platform or True Magistracy Restored, 1652]

To know the secrets of nature, is to know the works of God; and to

know the works of God within the creation, is to know God himself, for

God dwells in every visible work or body. And indeed if you would know

spiritual things, it is to know how the Spirit or Power of Wisdom and

Life, causing motion or growth, dwells within and governs both the

several bodies of the stars and planets in the heavens above and the

several bodies of the earth below as grass, plants, fishes, beasts,

birds and mankinde. [Ibid.]

Belief in an outward heaven or hell is a “strange conceit,” a fraud

by which men are delivered over into the power of their oppressors,

. . . a fancy which your false teachers put into your heads

to please you with, while they pick your purses and betray your Christ

into the hands of flesh, and hold Jacob under to be a servant still to

Lord Esau. [The New Law of Righteousness]

True religion and undefiled is this, to make restitution of the Earth

which hath been taken and held from the common people by the power of

Conquests formerly and so set the oppressed free. [A New Yeers Gift

for the Parliament and the Armie, 1650]

The earth with all her fruits of Corn, Cattle and such like was made

to be a common Store-House of Livelihood, to all mankinde, friend and

foe, without exception. [A Declaration from the Poor Oppressed

People of England, 1649]

And this particular propriety [property] of mine and thine that

brought in all misery upon people. For first it hath occasioned people

to steal from one another. Secondly it hath made laws to hang those that

did steal. It tempts people to do an evil action and then kills them for

doing it. [The New Law of Righteousness]

Now, this same power in man that causes divisions and war is called

by some men the state of nature which every man brings into the world

with him. . . . But this law of darknesse is not the State of

Nature. [Fire in the Bush, 1650]

. . . the power of Life (called the Law of Nature

within the creatures) which does move both man and beast in their

actions; or that causes grass, trees, corn and all plants to grow in

their several seasons; and whatsoever any body does, he does it as he is

moved by this inward Law. And this Law of Nature moves twofold viz.

unrationally or rationally. [The Law of Freedom in a Platform or

True Magistracy Restored]

In the beginning of time the great creator Reason made the earth to

be a common treasury . . . not one word was spoken in the

beginning that one branch of mankind should rule over another. [The

True Levellers Standard Advanced, 1649]

. . . the power of inclosing Land and owning Propriety

was brought into the Creation by your ancestors by the Sword which first

did murther their fellow-creatures men and after plunder or steal away

their land. [A Declaration from the Poor Oppressed People of England]

They have by their subtle imagination and covetous wit got the

plain-hearted poor or younger brethren to work for them for small wages

and by their work have got a great increase. [The True Levellers

Standard Advanced]

By large pay, much Free-Quarter and other Booties which they call

their own they get much Monies and with this they buy Land. [Ibid.]

No man can be rich, but he must be rich, either by his own labors, or

the labors of other men helping him: If a man have no help from his

neighbor, he shall never gather an Estate of hundreds and thousands a

year: If other men help him to work, then are those Riches his

Neighbors, as well as his own, for they be the fruit of other mens

labors as well as his own. But all rich men live at ease, feeding and

clothing themselves by the labor of other men and not by their own;

which is their shame and not their Nobility: for it is a more blessed

thing to give than to receive. But rich men receive all they have from

the laborers hand, and what they give, they give way other mens labors

not their own. [The Law of Freedom in a Platform or True Magistracy

Restored]

. . . if once landlords, then they rise to be

Justices, Rulers and State Governours as experience shewes. [The

True Levellers Standard Advanced]

. . . the power of the murdering and theeving sword

formerly as well as now of late years hath set up a government and

maintains that government; for what are prisons and putting others to

death, but the power of the Sword to enforce people to that Government

which was got by Conquest and sword and cannot stand of itself but by

the same murdering power. [A Declaration from the Poor Oppressed

People of England]

. . . the Kingly power sets up a Law and Rule of Government

to walk by; and here Justice is pretended but the full strength of the

Law is to uphold the conquering Sword and to preserve his son Propriety.

. . . For though they say the Law doth punish yet indeed the

Law is but the strength, life and marrow of the Kingly power upholding

the Conquest still, hedging some into the Earth, hedging out others;

giving the Earth to some and denying the Earth to others, which is

contrary to the Law of Righteousnesse who made the Earth at first as

free for one as for another. . . . Truly most Laws are but to

enslave the Poor to the Rich and so they uphold the Conquest and are

Laws of the great Red Dragons. [A New Yeers Gift for the Parliament

and the Armie]

Winstanley borrowed from the Levellers the idea that in Anglo-Saxon

England there had been an equitable sharing of land; and that at the

Norman Conquest great estates had been created, and the old population

dispossessed or driven into serfdom; and that this unequal division of the

basic wealth of the land had been perpetuated ever since solely by the

power of the sword; and that law and established religion were just

devices to uphold the sword; and finally, that the overthrow of the king,

the heir of the Norman power, had resulted in no important change. The old

laws still stood. A new Church, first of the Presbyterians and then of the

Independents, was established, and the grandees of the new commonwealth

were enriching themselves like William the Conqueror’s knights, while

the common people sank deeper into poverty. Winstanley’s interpretation

of English history has been considered naïve, but there is much to be

said for it. Anglo-Saxon England was in fact a frontier country, and all

through the Dark Ages, following the catastrophic depopulation that began

in the fifth century, there was much free land all over Europe and even

more in the British Isles.

He says of caterpillar lawyers that “they love money as dearly as a

poor man’s dog do his breakfast in a cold morning and they are such neat

workmen, that they can turn a cause which way those that have the biggest

purse have them.”

O you Parliament-men of England, cast those whorish laws out of

doors, that are so common, that pretend love to everyone, and is

faithful to none. For truly, he that goes to law, as the proverb is,

shall die a beggar. So that old whores, and old laws, picks men’s

pockets and undoes them . . . burn all your law books in

Cheapside, and set up your government upon your own foundations. Do not

put new wine into old bottles; but as your government must be new so let

the laws be new, or else you will run farther into the mud, where you

stick already, as though you were fast in an Irish bog. [A New Yeers

Gift for the Parliament and the Armie]

As for the church:

And do we not yet see that if the Clergie can get Tithes or Money

they will turn as the Ruling power turns, any way . . . to

Papacy, to Protestantisme; for a King, against a King; for monarchy, for

Some Government; they cry who bids most wages, they will be on the

strongest side for an earthly maintenance. . . . There is a

confederacie between the Clergy and the great red Dragon. The sheep of

Christ shall never fare well so long as the wolf or red Dragon payes the

Shepherd their wages. [Ibid.]

For Winstanley private property, but especially the property in land as

the source of all wealth, “is the cause of all wars, bloodshed, theft

and enslaving laws that hold the people under miserie.” Private property

divides man from man and nation from nation and leads to a state of

continuous war on which the state power flourishes.

Winstanley was the first to discover that axiom made famous by Randolph

Bourne — “War is the health of the State.” He also had the curious

and original idea that only in time of war does the power structure

encourage scientific invention. “Otherwise the Kingly Bondage is the

cause of the spreading of ignorance in the earth for fear of want and care

to pay rent to taskmasters hath hindered many rare inventions and the

secrets of creation have been locked up under the traditional parrot-like

speaking from the Universities and Colleges for Scholars.” War, says

Winstanley, makes the rich richer and the poor poorer and tightens the

bonds of power.

Winstanley was a devout pacifist all during the Digger experiment; and

one reason for the violent abuse of the Diggers, the destruction of their

shanties, and the injury and killing of their livestock, was due to the

fact that they put up no resistance. They believed that their example, if

only they were permitted to cultivate the commons and wastelands, would be

so infectious that soon it would be followed by all the poor of England;

and that when they had established a community of love, interpenetrating

all of English society, their success would lead even the rich and

powerful to join them, and eventually all Europe would turn communist

persuaded only by example.

Socialists, modern Communists, anarchists, all claim Winstanley as an

ancestor. In fact his ideas bear most resemblance to those of the

left-wing followers of Henry George’s Single Tax. For him the source of

all wealth was in land and its development in the application of labor to

the resources of the earth. If these resources were held in common, and

all men were permitted to develop them freely, and men labored in common,

then the resulting wealth, even of crafts and manufactures, would

naturally become communalized. Modern contemporary Marxists have called

this economics naïve, but it was held at the beginning of the twentieth

century by an economist who was anything but naïve, Henry George, who

attracted many thousand intelligent followers, and it is after all the

fundamental assumption of Marx himself. But it was not his economics that

was most important to Winstanley. What he sought was a spiritual condition

in mankind which would be in harmony with the working of Reason in nature

— the return of man, who had fallen into covetousness, to the universal

harmony. Winstanley’s communism was not an economic doctrine, but mutual

aid followed from his organic philosophy as a logical consequence.

After the suppression of the little commune of Diggers Winstanley was

quiet for a while. Then in 1652 he published, with a preface submitting it

to Cromwell, his plan for a new commonwealth — The Law of Freedom in

a Platform or True Magistracy Restored. The Digger pamphlets present

no plan for administrative or governmental policy. Winstanley seems to

have assumed that the example of small anarchist-communist groups working

in occupied land in brotherhood would sweep all before it and convert

England and eventually the world. The problems of self-defense and

internal disruption are met by total pacifism before which power must

simply dissolve. The violent suppression of the Diggers by both mob and

authority forced Winstanley to consider the question of power anew.

The Law of Freedom, after a general introduction, is concerned

largely with administrative plans, and the introduction is an appeal to

Cromwell to use his power to introduce the new commonwealth. If you do

not, says Winstanley, abolish the old power of conquest of the king and

nobles, but only turn it over to other men, “you will either lose

yourself or lay the foundation of greater slavery to posterity than you

ever knew,” a chilling forecast of the dark Satanic mills of early

British capitalism.

In the preamble he outlines the principal popular grievances, lack of

religious toleration, survival of the old priesthood, the burden of tithes

— a tenth of all income for an established Church, arbitrary

administration of justice, the old laws are still enforced, the old feudal

dues and obligations are still used to oppress the people, while the upper

classes ignore their feudal obligations and enclose or abuse the common

lands. These are the same grievances we are familiar with from the Hussite

Wars and the Peasants’ Revolt in Germany.

Winstanley points out that true freedom does not consist in free trade,

freedom of religion, or community of women, but freedom in the use of the

earth, the natural treasure of society, and that the first duty of the new

commonwealth should be to open the land to all people and to take over the

former holdings of the king, the Church, and the nobility. To do this

properly, and to use the land fruitfully for the good of all, society

needs true government, administrative officers who will be devoted to

freedom and the commonweal.

The original root of magistracy was in the family, and the first

magistrate is the father, as the finally responsible member of a group in

which all are mutually responsible. Officers of the society should be

chosen by complete manhood suffrage for all over twenty, and at first only

representatives of the old order need to be barred, although notorious

evil livers are not fit to be chosen. They should be above forty years of

age and hold office for one year only so that responsibility can be

rotated throughout the community. First are the overseers, the peace

officers who form a local council in each community. They preserve public

order and suppress crime and quarrelling and disputes over household

property and other chattels which remain in private possession. Others

plan the distribution of labor and assign the young to apprenticeships.

Others oversee the production of the craftsmen and farmers. Winstanley

envisages manufactures as being carried on largely in people’s homes

with a few public workshops. Apprenticeships normally take place within

the family; only boys who do not wish to follow their fathers’ trade are

assigned to the public workshops. Others organize the distribution of

goods and food which go to warehouses and shops, both wholesale and

retail, from which both craftsmen and consumers are free to choose what

they wish.

In each community there is a “soldier,” what we would call a

policeman, whose duty is to enforce the decisions of the peacemaker, a

taskmaster to whom is given the rule of those convicted of crimes against

the community and who assigns them to common labor. There is also an

executioner who administers corporal or capital punishment to the

hopelessly recalcitrant. Winstanley’s system of penalties may seem

excessively severe to us, especially in a utopian society, but in their

day, when people were hung for petty theft, they were relatively mild. In

the county or shire the peacemakers of the towns, the overseers, and the

soldiers, presided over by a judge, form the county senate and court of

first appeal. Over all is parliament, which Winstanley seems to have

thought of as primarily a court of final appeal, and he is very strongly

opposed to its indulging in promiscuous legislation. Laws should be as few

and simple as possible. What Winstanley had in mind was a polity like the

Israelites in the Book of Judges — in fact the neolithic village with

spontaneous justice administered by the elders sitting under a tree.

Curiously he says nothing about juries or any other form of

democratization of justice. Society defends itself by a militia and

Winstanley has a most perceptive section on the evils of standing armies,

militarism, and war.

Education in the new commonwealth is free, general, compulsory, and

continues through life. Everyone is to be taught a trade or a craft at

which he is to work part-time, whatever else he comes to do. No caste of

intellectuals or academicians set apart from the people by booklearning is

to be permitted to arise, although after the age of forty men “shall be

freed from all labor and work unless they will themselves.” The death

penalty is decreed for those who attempt to make a living by law or

religion. In each community there shall be a “postmaster” who

corresponds with all the others in the country directly and through a

central postmaster in the chief city. They exchange news, especially news

of progress in science, invention, and technology. Sunday is a day of

rest. The people gather to listen to a reading of the laws, the news of

the postmaster, and what we would call papers on learning and science.

Religious services are not mentioned. The people are apparently at liberty

to attend them if they wish. Marriage and divorce are civil, exclusively

at the will of parties, and take place by simple declaration before the

community with the overseers as witnesses.

Winstanley’s utopia has been criticized as being excessively simple

and himself as naïve; and even more naïve, his idea that Cromwell would

put in force such a policy, or probably even bother to read his pamphlet.

Ideological discussion with his sectarian opponents was, whenever he had

time, an indoor sport with Cromwell, but he never allowed it to influence

him. We must not forget he lived in a time of revolutionary hope. In those

days, as in the beginning of the Reformation on the continent, it seemed

quite possible to intelligent men that an entirely new social order might

be established. Everyone was something of a millenarian and believed that

a new historical epoch was beginning. They could not foresee the rise of

industrialism, capitalism, the secular State. To us, their future is the

past and seems to have been inevitable. There was nothing inevitable about

it to them. Perhaps if Cromwell, or even Luther, had foreseen the horrors

of the early industrial age in the nineteenth century, or the genocide and

wars of extermination of the twentieth, they might have chosen the

commonwealth of Winstanley or the community life of the Hutterites. In

each great crisis of Western European civilization, the Reformation, the

French Revolution, the revolutions of 1848, the First World War, the

Bolshevik Revolution, the Spanish Civil War, the Second World War, it has

seemed quite possible to change the world. It is only after the fact that

the historical process appears to be the only way in which events could

have worked out.

Was Winstanley’s utopia a workable polity? Within limits, yes.

Whether he knew it or not, it is remarkably similar to that of the

Taborites, the Moravian Brethren, the Hutterites, and the most successful

and enduring communalist settlements in nineteenth-century America. His

plans went into the common stock of ideas of later English communists and

directly or indirectly influenced John Bellers, Robert Owen, Josiah

Warren, William Morris, Belford Bax, Édouard Bernstein, David Petegorsky.

Other socialists, Communists, and anarchists wrote extensively about him

in the first half of the twentieth century and after the Second World War

he became extremely popular. Revolutionary communalist groups in England,

America, Germany, and France would even call themselves Diggers.

Although the Quakers are by far the best known and largest, and a still

surviving community descended from the Spiritualist Anabaptists, and hence

ultimately from the underground apostolic community of the Middle Ages,

they did not practice community of goods. Rather each Seventh-Day Meeting,

as they called their conventicles, had a common fund for the relief of

members in need. As a majority of Quakers became prosperous — due to

their strict honesty in trade and crafts and, prior to 1760 when they

refused to pay tithes and so gave up farming, their advanced agricultural

methods — these common funds became quite large and many poor people

joined the Society of Friends to obtain welfare funds vastly superior to

contemporary poor relief. At first this caused problems but within a

generation members who had joined for these reasons had been absorbed into

the general economy of Quaker mutual aid and poor Quakers were less than a

third of the proportion of poor in the general population, while

well-to-do members were proportionately three times as many. Quaker

welfare funds came to be used more and more for the general relief of the

poor in systematic ways which would foster self-help. Quakers were the

principal, almost the sole, financiers, besides himself, of Robert

Owen’s model factory town of New Lanark, and they have continued to

invest in communal and cooperative movements of which they approve to this

day.

In his youth at Manchester College Owen’s closest friends were the

Quaker John Dalton and another young Friend named Winstanley, quite

possibly a descendant of the great Digger.

Far more than Robert Owen, the most systematic theorist of a

cooperative labor colony was the Quaker John Bellers, who greatly

impressed Marx. Owen always denied that he was influenced by Bellers and

claimed that he had never heard of him until Francis Place showed him a

unique copy of his forgotten pamphlet in 1817. Owen immediately had a

thousand copies printed and distributed them to those he thought would be

interested, and so Bellers survived.

Bellers was born in 1654, a birthright Quaker. He became a friend of

William Penn and other leading men of the time. In 1695 during the long

economic depression in the last years of the century, he published Proposals

for Raising a College of Industry of All Useful Trades and Husbandry.

He called it a college rather than a work house or community because the

first was identified with the servile institutions of state poor relief

and the second implied that all things should be held in common. For a

capital investment of fifteen thousand pounds — worth considerably more

than ten times as much today — Bellers envisaged a self-sustaining

colony of three hundred adults with shops, commissary, crafts, farm land,

barns, dairies, pottery. The community was to be self-sufficient even in

fuel and iron. All members, from common laborers to the overseers and

managers, were to be paid in kind. The dwelling house would have four

wings — one for married couples, one for single men and young boys, one

for single women and girls, and one an infirmary. Meals were to be in

common. Bellers, like Winstanley before him, placed great emphasis upon

education in the humanities, in the arts, and in crafts and trade

combined. Bellers thought that the creative life of the community and the

advanced educational methods would attract many who would wish to come as

visitors or even permanent boarders; and even more would wish to enroll

their children in school, and for these privileges they would be expected

to pay well. He worked out in considerable detail the projected

bookkeeping of his community and demonstrated that the original investors

would gain a considerable profit, while at the same time the standard of

living of the members would be far higher than that of the contemporary

working class. The first edition of the pamphlet was dedicated to the

Society of Friends, the second to Parliament, but no one came forward to

invest in such a colony. During his remaining years Bellers issued a

series of pamphlets, some of them devoted to a careful economic analysis

of a semi-socialist economy, others proposing a league of nations, an

ecumenical council of all Christian religions, a national health service,

a reform of Parliament and the electoral process, a total reform of

prisons, and a reform of the Poor Laws.

Although Robert Owen had worked out his own system before he read

Bellers’s pamphlet and although Fourier, Saint-Simon, and Cabet had

certainly never heard of him, he anticipated most of their more

practicable ideas and in far more practicable form. Although all his

writings soon became excessively rare, he should be considered the founder

of modern, socially responsible Quakerism of the Service Committee

variety. Furthermore the various measures he proposed in his reformist

practice have almost all been incorporated in the modern welfare state.

Although Marx called him “a veritable phenomenon in the history of

political economy,” amazingly there has never been an edition of his

collected works nor, with all the immense flood of scholarly research and

Ph.D. theses, has anyone written a book about him. He is not even

mentioned in Beer’s History of British Socialism. Most

information about him is to be found in the final chapter of Édouard

Bernstein’s Cromwell and Communism. |

Kenneth Rexroth

|