Deep Tried Frees

Kaliflower, New Series (N.S.) 3, April 30, 1978

Three hundred thirty years ago, in England in the throes of the Puritan revolution, a

mystic named Gerrard Winstanley began issuing manifestoes against the clerical and

manorial establishments. He believed that God manifested directly in everyone, that

knowledge of Him through Scriptures was second-hand, that the priesthood was superfluous

and venal, that since all were equal in Godliness, none should oppress, tyrannize, or

reduce others to poverty, that penal, corporal, and capital punishment should be

abolished, that private property both tempted the poor to steal and killed them for doing

it, that the Earth should be held in common by all who labor it, creating a common

treasury from which all could draw according to need (including those incapable of

working), that none should give hire or take hire, and that buying and selling should be

abandoned, as it had become the art of thieving and oppressing fellow creatures. In a

vision, Winstanley heard the words, "Worke together, Eat bread together, declare this

all abroad." He [p.2] thought that the best thing a man could do was quit his job and

till the earth together with others, on the common lands, which at that time nearly every

English village still had. A few months after the publication of his fifth and most

radical manifesto, Winstanley decided to practice what he preached, and on April 1, 1649,

he and a group of co-workers began tilling common land near Cobham in Surrey. Within three

weeks they had been arrested and released twice, had had troops sent from London to

disperse them, had gotten an audience with the commander-in-chief of the English army, to

explain themselves, had gotten their explanation printed in a London news-sheet, and had

written their first joint manifesto, The True Levellers Standard Advanced, "a

declaration to the powers of England, and to all the powers of the world, shewing the

cause why the common people of England have begun, and gives consent to digge up, manure,

and sowe corn upon George-Hill in Surrey; by those that have subscribed, and thousands

more that gives consent." During the next year they continued tilling at several

different sites and even succeeded in putting up some houses, in spite of lawsuits, arson,

and beatings. However the pitch of the harassment increased, until their crops were

trampled and their houses torn down, and, when criminal indictments were brought against

them, the movement was effectively stopped. They called themselves "Diggers" or

"True Levellers" (in contradistinction to a less radical and more popular party

of the time called the "Levellers" —i.e., those who wanted to even out class

differences).

Twelve years ago a handful of socially conscious actors, inspired by the work and ideas

of the Surrey radicals, called themselves "Diggers," and (among other things)

began giving out free hot meals in the Panhandle of Golden Gate Park. Besides chicken-neck

soup, the latter-day Diggers provided or inspired others to provide free groceries, free

clothes, free breakfasts, free crash pads, free medical services, and an assortment of

free cultural events, from 1966 on. The Diggers' clients—if such a word can be used—were

the growing hip population of San Francisco, and in particular the street people. The

Diggers acted with wit and good humor, incredible speed and appropriateness. It is moot

whether the times crystallized the Diggers or the Diggers catalyzed the times. They worked

anonymously, had their own newssheet and word-of-mouth communication methods, and lasted a

year and a half, in a constantly [p.3.] shifting, hallucinatory scene, involving thousands

of people. The last event directly sponsored by the Diggers took place in June of 1968,

but free events and services in the same spirit, including sporadic hot meals in the Park,

continued for several years longer, even as hard drugs moved in and the focus of

activities moved off the street into the various communal households. The street, as it

were, burned down.

The soil the Diggers of 1966 tilled was not real earth but the garbage and surplus of a

wasteful, affluent city. Otherwise their work was remarkably similar to that of the

English Diggers: it was not merely an effort to help the poor but to free them from wage

slavery and show them what they really deserved and how society in the ideal could

operate. It is this political quality that differentiates Digger work from the missions,

poorhouses, charities, madhouses, and hospitals, which have been free in every civilized

country for hundreds of years, as begrudging institutions of last resort.

<<==>><<==>>

In 1966 I was in New York, putting together a print shop called Carp & Whitefish.

By mid-1967 I had one book printed (Marshall's Transit Glory) and another in the works

(Whalen's Invention of the Letter). The Marshall book was a fancy little contraption with

a drawstring that pulled the pages up from a pocket. It was to sell for a dollar, and I

was hoping to distribute fifty or a hundred copies to each of the half-dozen or so

bookstores in New York City that specialized in modern poetry. As I was planning to move

to San Francisco, either temporarily or permanently, I was eager to unload as many books

as possible in the East before I left. But the first (supposedly hip) bookstore I

approached placed so miniscule an order, that I resolved to sell the book on the streets

myself, and bought a two-dollar City of New York Peddler's License. But I was too busy

collating and binding the Whalen book to sell the Marshall book. A month after I got my

license I was on my way to San Francisco with both editions.

I arrived in San Francisco in early October of 1967, and by late November had helped

organize the commune I now live in. The commune grew rapidly, and early in 1968 the

Diggers started delivering free produce to our door. In April, following a Digger rally on

City Hall steps, Dave Simpson and Vinnie Rinaldi convinced me to send for my New York

print shop and set it up in San Francisco as a free operation. The conversation ran

something like this: "I hear you [p.4] have a print shop in New York."

"Yeah." "We could sure use a free print shop in San Francisco."

"How could I get it here?" (Vinnie:) "I'm willing to go to New York and

bring it back." It seemed like a hyperbolic offer, and I doubted whether someone

would actually go to that much trouble, but Vinnie did. I knew everything we printed would

be free from then on, but thought I had contractual-type commitments with the authors to

sell the two books I had brought from New York. In fact, authors' royalties had already

been advanced, so that was no worry. In May Richard Brautigan pointed out to me that free

was just as good a way to distribute a book as any other, and in reflecting on it, I

realized that a book could be given away to its rightful audience in one fell swoop. On

June 14, and with the author's blessings, commune members handed out 900 copies of the

Whalen book into the audience of a big free poetry reading at Glide Church, just as Philip

Whalen came to the podium. Free Wheelin' Frank's book 666 was handed out by the Diggers at

the same reading. The Marshall book was given out later at a couple of early gay

liberation events.

As early as August of 1967, the "Mutants Commune,"

a long poetic essay about American materialism corrected by Haight-Ashbury culture,

including free, had appeared in the Berkeley Barb. It spoke of the new communal culture as

having lasted only from September of 1966 to April of 1967, when it was done in by media,

tourism, commercialism, hard drugs, and violence. Certainly by April of 1968 these factors

had established themselves on Haight Street to the extent of taking away from the Diggers

their main stage and auditorium. Even before then, looking for a Digger was like looking

for an honest man: nearly everyone claimed to be one. The term was picked up by the media

and little by little abandoned by those who had borrowed it from English history. This

group, still rather small and tightly knit, began to think of themselves as the Free City

Collective, and in fact their eyes were moving from the Haight to the City. In April the

two main Free City projects were daily rallies on City Hall steps (a form of picketing)

and the taking over of a Victorian doomed by the Redevelopment Agency, on Verona Street,

in what is now the Yerba Buena Gobi. The daily rallies had the purpose of demanding that

city-owned empty buildings be restored to the people for them to rehabilitate and live in

freely, that surplus welfare food and materials be distributed [p.5] free through ten

autonomous neighborhood free stores rented by the city, that presses and trucks be made

available for the dissemination of free news, that resources be provided for autonomous

neighborhood celebrations, and that no permits be required for holding events in parks and

other public spaces. City Hall ignored the Free City demands; and the building on Verona

Street was demolished. On May Day a magnificent Free City Convention was held at the

Carousel Ballroom—an all-night acid-bathed dance. Then, a few days after the Glide poetry

reading, Free City sponsored its last event, the 1968 summer solstice celebration, which

was to take place in parks all over the city but ... just didn't. The Diggers had

spearheaded free in San Francisco for a year and a half—and they were pooped out—or

possibly not really interested in changing roles for the new play they found themselves

in. They retired from the scene gracefully, leaving behind a tradition and expectation of

free, which still lingers in San Francisco ten years later.

They also left behind a tangible summary of their ideals, the Digger Papers, a

twenty-four page collection of writings that came out in August of 1968 in two forms: No.

81 of The Realist and a free version that was handed out on the streets of San Francisco.

Paul Krassner gave the Diggers 40,000 copies of the free version for the right to

offprint it in The Realist. It is a mélange of original articles and material taken from

street news-sheets—a double-barreled blast at American culture, with Free City as a

prescription, sketched out as Free City Switchboard, Free Food and Distribution Center,

Free City Garage and Mechanics, and so on, through eighteen departments, including one

with the hair-raising title of "Free City Tinkers and Gunsmiths." (On the whole

the Diggers were non-violent in practice but not in principle.) A few years after it had

been distributed so plenteously, the Digger Papers vanished, perhaps because of its unpretty throwaway format. Few people now have even heard of this pamphlet, that for us

was once a Bible.

To return to June of 1968, the New York print shop arrived by U-Haul trailer, and we

set it up in the basement of the house the commune was renting on Sutter Street. We built

the darkroom with plywood supplied by Dave Simpson. It was he who taught us how to hustle

for materials. The Free Print Shop opened officially in August, and our first print [p.6]

job was a flyer for a Hells Angels raffle of Dirty Dick's chopper, to benefit his widow.

In those days we printed for any group or event that was non-profit and had reasonably

good vibes. Later our position about free hardened, and we refused to print for any event

or activity that was not completely free of charge or that did not state on its poster or

flyer that no one would be turned away.

In April of 1969, a seventeen-year-old new member took on as a work project the editing

of a free weekly newsletter for local communes—Kaliflower. It became the case of the

daughter publication growing bigger than the mother print shop, which turned mainly into a

production plant for Kaliflower. Kaliflower was issued weekly till the middle of 1972 with

a regularity that amazed even us. During that period we wrote about free frequently and

encouraged whatever free activities we could. We witnessed the founding of several free

stores, a film series, the Angels of Light, a free bakery, the Medical Opera, and a

Garbage Yoga service, from which you could order the household appliances you needed (its

specialty was abandoned stoves and refrigerators). In addition, there was a free book

store and a lot of individual items and services like blow jobs, piano tuning, and foot

massages, offered through the ads in Kaliflower (I wonder if all the free Aquarius kittens

ever got homes!). Probably the variety and quantity of free materials and activities

offered during the Kaliflower years matched those offered during the Digger

years—remembering that the "audiences" were different: street people in the

earlier case and communal families in the later case.

We helped initiate the Free Food Conspiracy, whose member communes pooled their

members' food stamps to buy food in bulk, which was then distributed to these communes

according to need. In our mind it was a watershed operation because, if successful, it

would have opened the road to pooling all resources and the possible buying of costly

things like land in the country and houses in the city. The Free Food Family, as it later

came to be called, the new name expressing homeyness and vague hopes for the future,

lasted about a year. It failed because it satisfied neither those communes eager to

communalize further, nor those communes unwilling to sacrifice imported cheese and

health-food extravagances for a common diet. Simply put, most participating communes

actually liked where they were at and felt no need to commit themselves more deeply. The

Free Food Family [p.7] actually was a kind of watershed, in that it brought us to the

absolute outside limit of intercommunal cooperation in 1972.

Both in 1649 and 1966, in the midst of a drastic social and religious upheaval, free

was put forward as an ideal whose time had come—a way of feeding and caring for a

swelling number of hungry and jobless people. But the three-year old free of 1969 had a

subtly different flavor, not only a different constituency. Among the Kaliflower communes,

free was not absolutely necessary for survival (though it made life a lot easier). For us

it grew into a way of expressing closeness. Nuclear family members don't usually buy and

sell to each other, are in fact communistic, and we wanted nuclear family intimacy among

the communes. We wanted a society of communes so unestranged that everyone felt like each

other's brother or sister. This became the raison d'être of intercommunal free, and free

became the communes' hallmark. So free was carried from 1969 forward, not strictly from

hunger. It showed itself to be an ideal with more strings to play than one.

During the time I had edited the Chicago Review, I had slowly come to understand that

my calling in life was art, and in those days—my late twenties—I took it for granted

that one tried very hard to earn one's living by practicing one's calling. But in truth,

only a small handful of all the artists I knew or knew of actually earned their livings by

selling their art-work. I asked myself what a work of art was worth. What is a poem worth?

When I edited the Review I inaugurated a policy of payment to contributors—$5, $10, $15,

$25—token sums, that would, I hoped, make the recipients feel as though their work had

value. But after I had written a book, and suffered the humility of seeing it treated by

the publisher as a piece of meat, and after I had seen my Marshall books, each one strung

with two beads, treated by a bookseller like Greenwich Village earrings, I came to the

conclusion that works of art don't belong in the marketplace, being qualitatively

different from pork chops and costume jewelry. They are emanations of the spirit and

cannot be priced. For what price tag can be stuck on a Moby-Dick?—which has by now fed

thousands of publishers, doctoral fellows, full professors, translators, grocers with

book-racks, actors, and make-up persons, not to mention the spiritually hungry—as if it

were the dining table of a king. When I came to San Francisco the last stone of this fence

of reasoning fell into place. Let others keep an [p.8] eye on the market and dollar-up

their art-work; as for me, mine was unpriceable—it was to be bestowed. Now this was not

an ego trip, but a recognition that my art-work was not mine, but of a spirit seeping

through me from the Great Behind. Or at times, it was less like a spirit and more like a

river of fire I stumbled into, that would rush into my body, snapping up my arms and out

my fingers like incandescent needles. Charge money for that? Rather rent the sky to

seagulls.

<<==>><<==>>

The question of livelihood arises: When you give away the work you like to do, how do

you earn a living?

Over the span of the industrial revolution, the phrase "earning a living" has

gradually lost its meaning. If the technological complexity of our culture were suddenly

whittled down to human scale—a hundredth the number of automobiles, no more skyscrapers,

freeways, jet airplanes, redevelopment projects, or electric carving knives—there would

be vast unemployment, because machines under electronic surveillance would be doing most

of the work. (Only the lag between the growing spiral of superfluous technology and its

automation keeps so many arms and legs employed.) In fact, there is a good, enlightened

sentiment for abandoning the industrial revolution entirely and returning to

labor-intensive production—just to keep people busy and happy. In other words, you are

not really earning a living at all. You are doing meaningless work or busy-work, and you

are paid for it in part to keep you from fomenting a revolution. Why not use the machines,

junk the gadgets, and pay people just for being alive? That is a philosophical, perhaps

aesthetic, question beyond the scope of today's lecture. The point here is that, on

technological grounds, "earning a living" has lost the meaning it had to

eighteenth-century farmers, bakers, millers, masons, cutlers, wainwrights, smiths,

coopers, tailors, and all the rest of the artisans, which our antecedents were, in fact

and in name. If earning a living is a sham, and not a righteous and honorable activity,

why waste time doing it, if you can possibly survive some other way? And if you

can

survive some other way, why not become the skilled craftsperson you've always wanted to

be, and give your wares away to whoever needs them?

Buddhists, particularly local ones, make a great fuss about right livelihood. But what

does right livelihood mean in a capitalist-corporate-multinational [p.9] nexus of greed?

Every aspect of our lives is tainted by excessive profit-making, real-estate speculation,

stock-market manipulation, price-fixing, armament-making, hard sell advertising,

conspicuous consumption, unfair labor practices, automobile proliferation, urban

"redevelopment," chemical pollution of food, air, and water, deforestation,

strip mining, chicken farming, genus-cide of mammals for their skins, tusks, fur or meat—the list of

et ceteras would fill a book. Even if you have become a simple craftsperson,

it is impossible to rent your shop, buy raw materials, or accept payment for your products

without implicitly supporting questionable businesses or business practices. Not once in

my forty-seven years have I ever been asked, by some soulful shopkeeper, to provide a

pedigree of the money with which I paid for something. In this society money protects, by

hiding from view, any immoral activity used to gain it. If you really want to practice

right livelihood, there are not many choices open to you. You can secede from society and

set up an independent community with your friends, along the lines of the Farm in

Tennessee (not to grant that they are totally clean either), with its own system of work

and trade, or you can become an outlaw, so far as your survival income and work output are

concerned, somewhat along the lines of Robin Hood. Being an outlaw means that the very

method you use to gain your income and supplies, and the very method you use to give back

to the world the products of your work, help subvert the economic system in force, while

supplying the justice and compassion it lacks. It is not enough to subvert the economic

system—a bank robber can do that—nor to tilt it in the direction of the small and

human—as cottage industries and the Briarpatch Network seek to do. A small business may

be excellent personal therapy for individuals trying to drop out of the rat race, but its

effect on the economic order of things is dubious. There is no economic difference between

a hip food store run by a former advertising executive and a straight food store run by a

person who would take over Safeway if possible but lacks the know-how or capital.

Multinational capitalism is merely small business grown big. All monsters look cute—and

harmless—when they're kids. But without a deliberate, built-in dwarfing, kids tend to

grow up. Right livelihood, down-homeness, simple living, and other such good intentions

are not in themselves such a dwarfing. Free is.

[p.10] Business is an addictive disease like alcoholism. Most cured alcoholics know it is

better not to drink at all than to try to drink moderately. Reading the Briarpatch Review

has always made me uncomfortable. It is like reading testimonials of a bunch of ex-lushes

trying to convince themselves they know how to drink moderately. Or it is like reading

sentimental confessions that buying and selling, supply and demand, and the whole system

of money, market, and accumulation of capital are really not as bad as they've been made

out to be, in fact, if you look at them the right way, they're even kind of cute.

Finally, for many of us in the arts, the guaranteed annual income has already arrived,

in the form of foundation grants, CETA, CAC, NEA, or SSI—not to speak of Medi-Cal and

food stamps. Some people say that artists are a special and atypical segment of society,

but I believe along with Pindar(?), that "when the poets change their modes, the

walls of the city tremble"—i.e. that artists are harbingers of what the rest of

society will be doing presently. I remember food down to a half-box of rice on the shelf

in New York—just seventeen years ago—and I am thankful for no current survival

worries; and it strikes me as piggish for an artist with guaranteed subsistence to want,

besides that, royalties, admission percentages, and so forth. (Every once in a while, a

shiver of paranoia runs down the back of some artist I know, and he or she says,

"What if our grants get cut off?" And I say, "What if they do? Then you'll

go back to selling your ass, your time, or your art-work, just as you used to."

"Won't we have forgotten how?" "Hunger will provide a one-day refresher

course.")

Free is just as pertinent a stance as it was ten years ago. Greed and selfishness are

plump and healthy, in their corporate and sleek new multinational mink coats. Of course

now there are the People's Food System and other such "socialistic"

enterprises—for those who like to see the "revolutionary" price of

"revolutionary" Rice Krispies lit up on "revolutionary" cash

registers.

How different free is from those dubious, dreary financial statements on the last page

of the CoEvolution Quarterly, which purport to tell all, but which turn red or black,

increase or diminish at the whim or interpretation of the editor. Why does he bother? Why

does he want us to think there is really something there to [p.11] scrutinize? Can we

audit his ledgers or alter his plans? (The CoEvolution Quarterly is a good example of what

we may call reform capitalism. The idea is that if you seem up-front about your financial

operations or set aside some of your profits for known worthy causes or set yourself up as

a non-profit foundation, you are automatically absolved of responsibility for the economic

system you swim so well in and support so faithfully.)

Free makes a shambles of the immutable laws of profit and loss. It makes the scoffers

scratch their heads and say, "Somebody has to pay for it somewhere along the line."

(The answer is, "You can sell your brand of economics back to the Harvard Business

School but I wouldn't take it for free.") Free puts magic back into everyday life.

It

is the gratuitous act. It reminds us that humor and playful illogic are part of the human

condition. Not a hundred New Games Tournaments, that the CoEvolution Quarterly could

sponsor, would make up for one of its deadly, contrived financial pages. Free points out

that money in our culture has become the end rather than the means, and that when you

suddenly off it, people still have to get what they need from each other—where the focus

should be.

Free sends a shiver down the spine of those who use the same green measuring stick to

measure everything. And the idea that something may be available which they cannot buy

frustrates and alarms them. As for the folksy "green energy" folk, those who

conceive of money as a big cloud of potential goodness, somewhere away in outer space,

moored beside psychic and nuclear, they don't know whether to consider free a friend,

enemy, or another kind of energy.

Free strikes a chord in the hearts of the poor—the joy of being invited, rather than

prevented, from doing something. Think of going to a movie you've always wanted to see—a

good movie—and it's free—and you don't have to worry about whether you can afford it—or

if you'll be caught sneaking in—and you tell all your friends—and even if you forget

your wallet it won't matter—and there's no harpy standing over a donation box to make you

feel guilty—in fact there's no donation box—it's really free—completely free.

Free would strike a chord in the hearts of the well-provided if they let it—the joy of

"treating" everyone and showing them the same charming bourgeois manners usually

reserved [p.12] for guests and relatives. "Ah, Mr. Street-person, one lump or

two?"

Free gives poor people what they otherwise might not be able to afford or enjoy, and if

the quality of the free work is good, teaches them what they deserve. (I cannot resist

quoting Allen Ginsberg's answer to the question why he doesn't spend more of his time and

energy working with humble people, the salt of the earth, rather than with college

students and other middle-brow audiences: "But the salt of the earth don't need

enlightenment. The most debased people need enlightenment, the matter-habit freaks of

Middle Class.")

Free frees the artist from the need to trick, mock, or flatter paying customers, and so

gives him or her a most dizzying freedom of expression. Free also removes any excuse to be

slick, kitsch, or "professional," forcing the artist to be true. But you have

to start out with a little on the ball, because if you are an out-of-touch artist turning

out work that no one wants because it is bad or unclear, making it free doesn't help

anything, in fact gives free a bad reputation. It is especially important for free art to

be smashing, to overcome the common prejudice, that what is given away is inferior or ulteriorly motivated.

Free abolishes a lot of banking, bookkeeping, and bill-collecting, but even more

important, it stunts the growth of your project and keeps it small and personal. Free is a

built-in safeguard. It keeps your project from developing a mass orientation with hundreds

of employees and from accumulating profit to capitalize with; on the contrary, the more

you give away, the more you lose. The more successful you are, the more you lose. So you

stay small to stay open.

Free fits hand in glove with the two other best remedies for our over-industrialized

culture—remedies that any citizen can practice, that you don't need a Red Army to put

into effect: keeping small and keeping personal. For an artist, the three remedies

together prescribe a few do's and don't's which many of us have been practicing in San

Francisco for a decade quite happily. The list sounds strangely like religious advice, and

perhaps that is no coincidence. Work anonymously, abstain from mass media, don't be a

star, focus on your work and not on your professional identity, serve only the people you

can talk to and talk to them, give up ambitions of wealth, fame, and reaching a mass

audience.

[p.13] For a long time I have recognized religious overtones in the work of

"irreligious" artists, indeed in the work of ordinary school teachers, working

people, cafe owners, and even officials of the Redevelopment Agency. Since it is almost

universally recognized that religious instruction must be free and available freely at all

levels of society (occasionally you find corrupted religious teachers fat as bedbugs,

charging for their services, especially in New Age, Aquarian, holistic cults), it would

seem logical for anyone whose work sends out these overtones to set it free. And even if

you are unsure of yourself, and think there is only a possibility your work in the world

may have a religious quality, why not give us all the benefit of the doubt and set it

free?

Free may not be as ancient, hallowed, or exalted an ideal as some, but it carries its

weight. It will "swell a scene" of ideals and help one get through hard times

faute de mieux. In a pinch it can expand to be a project's sole ideal. I had a chuckle a

year ago over a remark made by a member of a local free theater group. He said, apropos of

a benefit they were thinking of giving for themselves, "Well, the world won't come to

an end if we do a paid show." True, the world will keep on spinning as it always has

before, but what would come to an end is this theater group, held aloft as they have been

for several years now, solely by the ideal of free. An ideal for them or anyone, almost by

definition, is a bit difficult to achieve, so you can expect to have problems with free.

The main one is that it puts you out of step with the rest of the world, so busy tapping

pocket calculators—but all good ideals do that. They put you out of step so everyone will

look at what his or her own feet are doing—so don't fret, float.

<<==>><<==>>

It would be instructive—from a tactical point of view—to go over the list of those

who oppose free the most strongly.

First of all, there are businesspersons who believe in what they're doing (happily a

godawful lot don't). Argue with them if you think it will do some good, but if you want

something from them—their usable garbage or a special discount—better pass yourself

off as another sucking charity that vacuums up the dregs of their economic system, to keep

their sidewalks clean.

Some ordinary working people are hostile to free because if they took it seriously,

they would see their own lives as thrown away or worthless or themselves as

fools—somewhat like the gold star mothers who supported the Vietnam War.

[p.14] Then there are young entrepreneurs—hip people on the make. They have just come up from

where they think you are, they know all your arguments, and it's going to be mighty hard

to convince them to go back down to the floor they've just got up from. Sometimes they are

as rabidly hostile as new converts. However sometimes, especially if they are dope

dealers, just a mite guilty for living off the counter-culture, they may be of some help.

Does anyone know how to get money out of Bill Graham?

A lot of artists who jumped on the bandwagon of free in the late sixties and early

seventies, because it seemed the hippest thing to do, have abandoned it with disdain, now

that it is no longer a fad—as if no principle was more important to them than being

"in." Since, by making free chic, Kaliflower encouraged them to stuff their

heads with it, I suppose they should be allowed to pull out the old fashions like straw

and stuff in the new ones, without being made fun of—at least by us. (But it does tickle

the spirit to see these mature men and women who once "loved Kaliflower"

flaunting their new punk life-styles—who once wore patchouli now wearing razor

blades—who once smiled mindlessly now sneering mindlessly.) As for those fleas of

artists, who hop on free because they're not making it elsewhere, and hop off free at

every possible gig, and argue about it besides—why don't they find some other old dog to

live off and give us a break?

The word "free" has several different meanings. Some people cash in on the

ambiguity and others use the word fraudulently. For example there are "free"

schools and universities which charge tuition. There are "free" offers of things

you must buy something else to get. There are "free" events at which

"donations" are expected and practically extorted. It goes without saying that

when you accept a "donation" for a "free" service, you are selling

something, not giving it away.

Some counter-culture and hip non-profit groups are frightened by free. They more or

less understand it and wouldn't bad-rap it, but they are cool and unhelpful; free

threatens their own base of economic existence (invariably some form of petty capitalism

beefed up by government subsidies direct and indirect). They put free down as ivory-tower

idealism and see themselves as revolutionaries practicing economic realism (as a stage on

the road to socialism). The tactic here is to make them understand that their realism is

as hokey and concocted as anything the dreamers might have thought up. It is especially

exasperating [p.15] for them to insist that we relate to them on a pay-as-you-go basis,

while at the same time they are ripping off all this free money from the government and

elsewhere. Here I could list all the grant-supported dance and theater groups we have

never been given free tickets to. The tactic is to persuade them that they are not the

Bank of America (yet)—just a bunch of hippies groping their way through the cesspool of

capitalism, that any course is bound to be filled with contradictions, and that they

should strive to keep open, flexible, and generous, and that if somebody should insist on

a free ride out of poverty or scruple, they should just let them get on without

kvetching.

In general private foundations and government art councils are horrified by free. They

are manned and womanned by gentlemen and ladies who believe in free (!) enterprise or

have to look like they do. They like to think they are supplying seed money for a project

to get on its feet with, and want the project's beneficiaries to support it. Truth is, the

project doesn't really have to be self-supporting, just has to look like it's trying. It

makes them feel better to think that a project is struggling to survive but can't quite

make ends meet (without their help). They don't like parasites. That they and their

families and their foundations are not self-supporting doesn't enter their minds. When

applying for grants it would seem practical to play down the free aspects of your work.

Free is not the end-in-all of the universe—just a humble handy practice to set some

things in it straight. It never really caught on except in Surrey and San Francisco, and

for all I know may need a highly specialized environment to thrive. There are dozens of

other remedies, of equal potency, for the world's various ills, and each remedy has its

advantages and drawbacks. Use free where applicable. It would be a mistake to stick to it

rigidly in a situation or place where it wouldn't work or be comprehended, just as it

would be a mistake not to try it out, because of preconceptions about its practicality.

For example, a free soup kitchen in Tangiers would probably get all the local soup kitchen

proprietors upset and you busted. However a cheap soup kitchen that subtly lost money

could probably fly. You can never ignore the local ecology, on the contrary, you have to

know it well. You have to know what you can get away with and what strategy will be most

effective, to right the wrongs you want to right.

[p.16] You may decide that you have some overriding reason for addressing a (paying) mass

audience—knowing you can hardly do so without debasing its cultural aspirations—for

every mass address feeds the monolithic media and turns human beings into TV-magazine

boobs without a real culture of their own. But nevertheless you may feel that what you

have to say is of such overriding importance and must be transmitted so immediately that

you are willing to turn a few more brains to mush to do it. Poet, that is a decision for

you alone to make—in the company of your conscience (who is hopefully not just a stand-in

for your ego). (I know that I myself have stopped reading certain poets in protest of the

shoddy, disposable, machine-made quality of their books. It is a paradox of sorts, not

reflecting well on the poets in question, that when they were poor and unknown, and glad

to accept any publication offer, lovers of their work prepared beautiful, virtually

handmade editions of their poetry [cheap, too!], but now that they are famous with a

choice of publishers, those whom they have chosen make their books ugly, non-rebindable,

uncomfortable to the hand, and inconsiderate of the reader.) But poet, if you do make that

decision to blast away—take an afternoon off, take a walk into the sunny Mission, where

avocado trees grow fifty feet tall; bring us a copy of your latest book inscribed in your

own hand; make believe you wrote the whole tome just for us chickens; apologize for the

garish dust jacket; let us know, while sipping a lemon phosphate made from home-carbonated well-water—while we are sipping a cup of artfully acquired Jamaican Blue Mountain

coffee—a drug we use only to write last paragraphs with—, that you are sorry not to have

served the muse of free but grateful to have served a muse at all.

[end]

[originally posted 1996-02-24. Stylistic typos from first transcription

corrected 2020-06-10: em-dash substituted for dual hyphens; spacing fixed;

underlined words in original text are now italicized. Printers devices (<<==>>)

inserted to denote breaks in original text.]

|

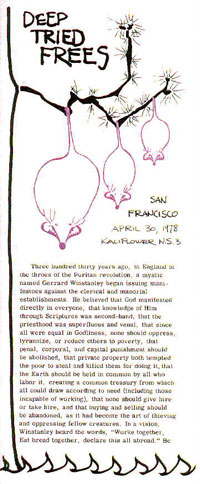

Cover of the special issue of Kaliflower N.S. 3, Apr. 30, 1978.

Deep Tried Frees was printed and assembled at the Free Print Shop in the

Mission District of San Francisco and distributed at the first Haight Street

Fair. This was also the occasion of a memorial service for Emmett Grogan

held that day at the Grand Piano on Haight Street.

|