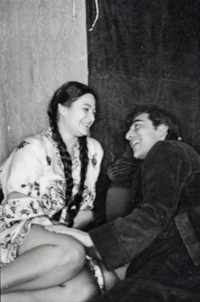

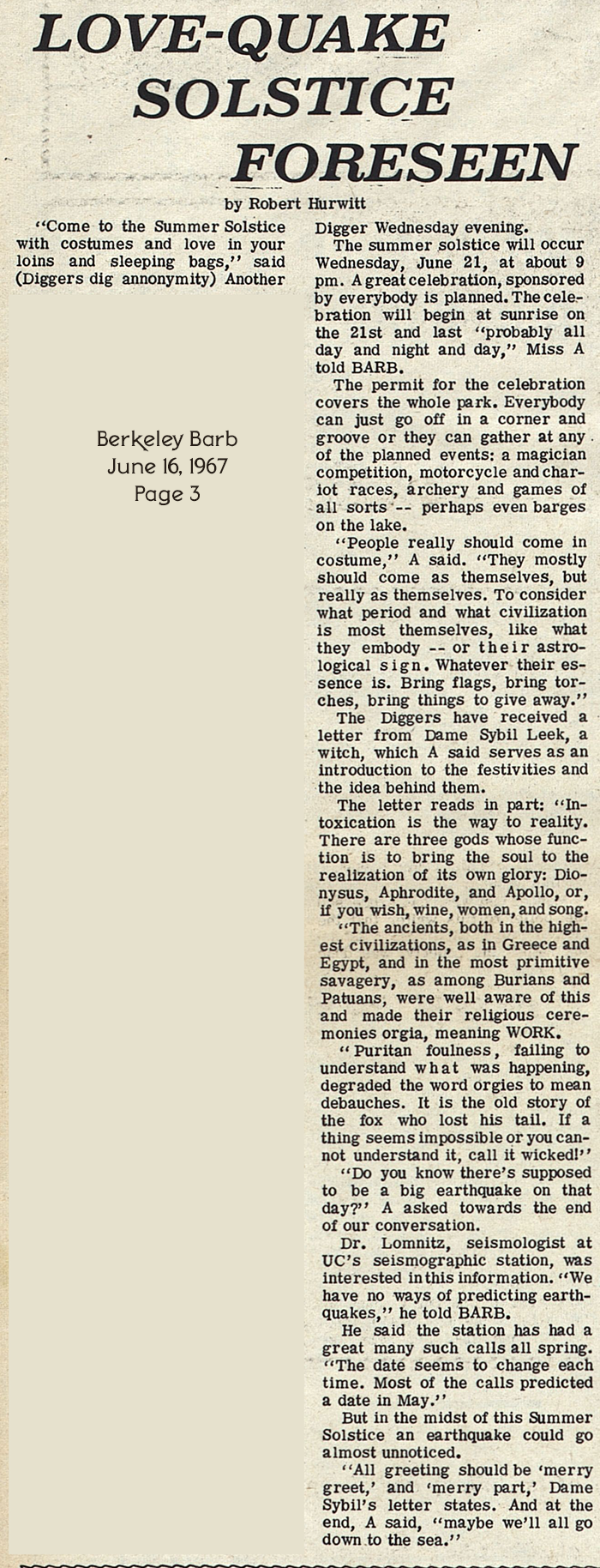

The Full Interview with Lenore Kandel

by Alice Gaillard and Céline Deransart, 1998

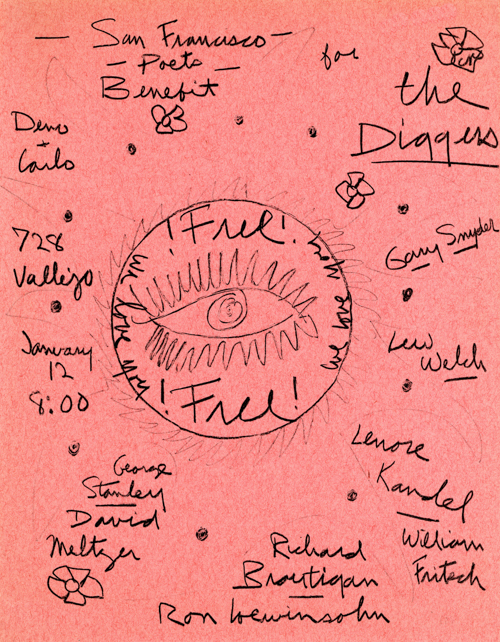

[Many thanks for the anonymous donation which provided for the digitization of Alice's and Céline's filmed interviews for Les Diggers de San Francisco. Also, a big thank-you to Jay Babcock for his transcription and editing assistance. Jay's Diggers Docs site is another source rich in Digger history. Addenda: Jay has written a moving tribute to Lenore. Check it out.]

Note: Interviewer questions are mostly inaudible in the recording; questions in brackets are best guesses as to what was being asked—JB.

[Q: How did you come to be in San Francisco?]

I had come from New York to LA. I drove across country with a friend. I was

living in a rooming house and I was typing scripts for an old man who had six

fingers. And he was a mime. He had me write letters to colleges and places

saying that he would come to them for an interview in the costume of an old man

— of course, he was an old man. [chuckling] I thought it was rather

clever.

A friend of mine was going to drive to LA. So I decided I'd go along. So I gave

him back his manuscript, and packed my things, which were very small at that

time, and got in the car. The old man was hanging out the window of the rooming

house saying, Have I offended you? With his six fingers hands, waving. And I

said, No, no, no, I'm just leaving. And we went across country very quickly. I

think it was 1960. I would, I wouldn't guarantee it. But I think so.

When I reached L.A., I decided… I'd never seen San Francisco! So I took a

Greyhound bus to San Francisco. And I had two addresses — I had the address of a

friend of mine who lived near the Bread and Wine Mission, and I had the address

of a hotel that was cheap on Broadway. When I got off the bus, a cowboy had a

suitcase of fireworks. He was going to a rodeo in Oregon, and he gave me a Roman

candle. So I took my Roman candle and asked a cab driver how to get to North

Beach. He told me what bus to take and I took it and I got there and I met Lois

Delattre, who was connected with the Bread and Wine Mission. But my friend

wasn't living there anymore, she'd gone away.

I ended up living in the attic of East/West house, which was a place that Gary

Snyder had started, mostly for Zen students. At first it was all males, then it

got turned coeducational, and then it got to be people from all over the world

who lived there. It was small. I lived up in the attic, because there wasn't a

room for me. But the thing is, there was no floor in the attic. I had to walk

over these planks, boards, a very narrow way back to a window where there was a

mattress and I could look out the window as the fog rolled in. It was beautiful.

[Q: What did you do?]

I was a folksinger. I mean, I was a poet, right? And I was always doing at least

two things. And I made my living. I sang on Grant Avenue in North Beach, at the

Coffee Gallery. And I sang around the corner in a bar. And I sang at other

places too. Then, later, I was belly dancing in one cafe and I was singing in an

Israeli show at the same time, so I had to get out of the show, put on a trench

coat over my costume, and run down the street. And all the tourists were saying,

you know there's a girl that looks just like you [chuckles] in the show

up the street. And I would run back and forth.

And meanwhile, well... When I first came to town, I'd left some of my poems at

City Lights. Someone took them and published them in Beatitude. And [once] I

walked down the street, and they were all shouting my poem on the street. So

that was kind of nice for an introduction.

[Q: And you met some Beat poets then?]

I guess so. Some. I don't know. I met people. I found it very exciting.

It was all very new to me, though. I ended up in the middle of everything

instantly. I think I'd only been here maybe a month or two before I went to Big

Sur with Lew [Welch] and Jack Kerouac. I don't know… I just met a lot of people,

and I was somehow in the middle of things instantly, and it was very exciting to

me. And it was very beautiful, physically. I did a lot of walking around the

city and up north and I liked it very well. I had all my money tied up in a

return plane ticket to New York, but I cashed it in and stayed here. Got my

guitar and, well, I sang in the coffeehouses.

[Q: How did you get involved with the Diggers..?]

The first thing was the

Invisible Circus at Glide Church, which was incredible.

Peter Coyote, he's the one I think that called me and invited me to the Artists

Liberation Front. The Artists Liberation Front was a group of very intelligent,

very wild people with connections in various arts— music, drama, writing…

probably everybody doing everything and wanting to change the world — wanting

for the world to change itself, to wake up. And the first thing that

happened was the Invisible Circus. It was Peter Coyote, I think, that first

called me to attend a meeting with the Artists Liberation Front. And Bill

Fritsch and I went, and immediately became involved with everybody and with the

Invisible Circus, which was… [pauses, thinks] a manifestation of both the hidden

and overt minds of the people of the time, which encompassed an incredible

variety of unbelievable actions.

Everybody took different rooms of the church and developed their fantasies.

Peter Berg and I worked on one room together. And I had foot readers [there], so

that when you entered the room, you had to take your shoes off, because it

seemed a good way to wake people up. One was my most eccentric friend, and the

other was a Hopi Indian woman that I knew that was an art student that was here.

And I helped make up the chart. And then all sorts of things happened. At one

point, they were showing defense films of [Viking?] missiles, and the screen was

exploded by a bevy of belly dancers, and an orchestra [just] wailing.

It was incredible. Sweat was flying through the air, clothes were vanishing. It

was so crowded, you couldn't breathe. Police and reporters that happened to come

by any of it just left—they couldn't face it, there was too much for anybody to

believe was really happening. It went on for three days.

[Ahead of the event] I had spent a great deal of time going through all the

personal ads in the Berkeley Barb and such, papers where people wanted…anything

to happen — you know, strange personal ads. And I called every one of the ads,

[and told them] whatever it was they wanted, I'd tell them to come here this

day, and they'd get it.

People had unbelievable hangups, which they went through during the course of

this weekend. People were shooting up on the altar, doing all sorts of very

strange things. And naturally, the people running the church got terrified. So

they called us in for a meeting. And… [backtracking] There was a bus terminal

nearby. So [we] were getting people from all around the area in there. And I'd

called up all the various religions, and suggested they bring their

missionaries, because I always thought it was unfair that Christian missionaries

went to all these countries and tried to convince people, I didn't see why their

missionaries shouldn't come convince us— [which just happened!] So they

showed up there.

We got a bunch of psychotic chickens from the psych lab at Davis. There were a

lot of things happening.

It went on till everybody panicked. And then they [the Church] asked us to move

[the attendees]. And I did something which I still feel odd about. There was a

newspaper being published, and I wrote something that convinced everybody to go

out to the beach. And everybody did. And then I went home. I'd been up for two

nights, and I was pretty tired. I’d just got to sleep when I got a phone call

saying, Come back, come back, because everybody's coming back from the beach,

and they've all had religious experiences and we need you. And so I went back

and it was… [pauses] That was what made Glide Church. People really

had gone through themselves and they came out the top of their heads. And

they felt wonderful, and they felt connected, and they felt holy in everything.

Wholly holy. And they were coming to the altar and laying souvenirs of

their trip: seashells, incense, clothes, feathers, whatever they had. They were

really connected. And then there were a lot of discussions.

[Q: There were drugs like LSD being used during Invisible Circus?]

Oh yeah. Everywhere. I didn't take any. No, there wasn't time. I'm sure a lot of

people did, though.

[Q: Why did you choose that church?]

Well, that was happening before I got there. There was a discussion about that.

It was a place… Nothing much was happening there, then. It was a very large,

empty building. And it was many stories tall—there was a lot of room. And it…

just called for it. And it turned out to be a very good thing, it's what started

Glide Church, turned it on to ‘the streets’— the street people and the church

became one. And it’d never happened before, [and it’s continued] into the

present day. It was a wonderful happening.

[Q: What was the reaction from the Church officials?]

Before it happened, there was a straight Methodist minister in a very small

congregation of aging widows—no connection to anything, really. After that, he

really found a calling, he became a true minister—because he dealt with the

people that actually lived there in the Tenderloin, in the streets, and

became a very valuable service. The church became the first living, functioning

church in a long time. And still is, a long time later.

[Cecil Williams, the new minister] responded to it. He was frightened by it at

first, which is not surprising. I mean, anybody could have been. But then he saw

the value of it, when the people came back from the beach, and began testifying,

in truth. When people actually had true, religious experiences, he found his

calling. It was a true one, wasn't fake. And he has been practicing it ever

since. It was actually beautiful. But it was a hard way through. I mean,

incredible things happened there that night. But what happened was real.

[Q: About how many worked on it?]

Oh, maybe eight? Maybe nine? Not very many. It doesn't take very many if you

really put yourself completely into it. We did an amazing [number] of things

with not that many people but [laughing]... [we were] very busy, very tired

people. I mean, it just took all your time.

[Q: So then you started working more with the Diggers?]

Yeah, well… I worked with everybody, with all those things… because it

was fun. And it made sense. We were trying to change the world. It

was also where I discovered that some people just follow. The idea was to show

the way, and I was really very disappointed when I discovered that some people

will simply sit there with their hands out, waiting. And they'll never pick it

up for themselves. They just want a leader. We didn't want to be leaders. We

just wanted to be… pathfinders? Guides. Signposts. Flags. [laughs] 'Follow

this.' But some people just wanted to be told what to do, wanted to be given

written directions. Others, however, picked it up and went on from there. It was

very exciting.

[Q: The Diggers were people who knew how to organize?]

No, we learned as we went along. Whatever it was, if you really wanted something

to happen, if you had something... Like, alright, what I wanted to have happen

was I wanted to hang wind chimes in all the trees in the meadow in Golden Gate

Park. There was a music thing happening. And I thought, I've always liked wind

chimes. And I said what I wanted to have happen, and they gave me as much money

as they could, and I went to Chinatown and bargained with all these stores for

Chinese glass wind chimes and I came back carrying shopping bags full of Chinese

glass wind chimes, and then we went and hung them in all the trees in the park.

And I also had crystal prisms that I hung in the trees. And they were all there

for people to take. Just think of it: a soft summer afternoon, and you're in a

park and there's a band playing music and you look up into the trees, and among

the branches are chiming colorful glass wind chimes, hanging over your head. And

when you're ready to go, you just reach up and you take one, and you take it

home with you. And it chimes for you forever. There's one in my kitchen now,

from that day. It was very nice.

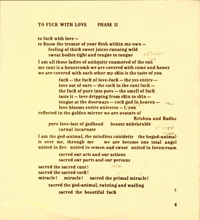

[A question mentioning poetry]

We were poetry. [chuckles] Yeah. It was a very busy time. Poetry

was...well, you know, it's part of, it's me. I mean, I always did that. But the

other things go along with it. I mean, it's not a separate part of life to me. I

felt it was very important not to be academic, not to live in a world apart from

everybody else, not to play back-and-forth between people who already agreed

with you, but to sort of…shine out everywhere. Maybe it would come in handy ten

years later for someone. It seems to have worked that way.

[Q: Could you tell us more about the Diggers ‘free’ philosophy?]

"Free": that was probably the most unique thing [about the Diggers].

There was the free store where you came in and got the clothes you wanted by

looking through them and picking out what you wanted and going home with it.

People gave things. We asked for things. There were always people that worked

there. There were some people that were so hung up they had to come in and

steal from the free store. [laughs] They couldn't just take it. Then there

was free food, which took an enormous — boy, I did so much cooking sometimes.

Everybody did. I mean it was a lot of work to it all. But it was good

hearted. Some of it was insane. [laughs] Most of it was legal.

[chuckles] There was an awful lot of stuff that was just thrown away in the

society. We used to go out to the fields and glean them after—cannery

fields—vegetables and fruits that were too large were left behind. Especially

zucchini. We had way too much zucchini. Truckloads of zucchini, huge

zucchini. Everyone you knew was eating the same thing the same day. I mean, you

were tired of whale heart and zucchini — but everyone you knew also was

eating whale heart and zucchini. [laughs] You're gonna hope they'd find a better

recipe than you found [when you were preparing the meal]. I mean, I found whale

meat Sauerbraten worked pretty well. But it was difficult. [laughs] It was

challenging. But it was still fun.

Free food, free clothes, free food in the park... Giving people back what they

already had actually is what it came down to. It was the 'free' that was the

largest... Free entertainment: the bands and music in Golden Gate Park. And,

well, actually that brought a whole lot of the bands into prominence. Rock

music. The free things in the park... The Communications Company putting out

flyers, poetry, comments and everything else on the street. It was bringing

everything to everyone and all of it free. Now money had to come from

somewhere, and some of it was… a lot of money was donated from a lot of strange

places. There was the free bank: when you wanted money, you would go to the free

bank and if there was money, you got it for what you needed. Some people needed

a lot more than other people. [chuckles] There was a lot of dope. There was a

lot of acid everywhere, yeah.

[inaud question]

Well, freedom equates with responsibility. This is something that disappoints

some and enlightens others. To be free means you have to be responsible for

yourself. This is one of the things that some people are still desperately

fighting not to understand. And I think it's the only way we can ever get

out of where we are, to go another step higher. All these free things belonged

to us and belonged to whoever wanted them. But it had to be [that] what you took

you were responsible for...whatever you wanted to do with it. But it became

yours, when you took it. The fact that freedom and responsibility are two

sides of the same thing seems still to be a mystery to many people.

We did not totally succeed; however, we succeeded pretty well, at least for a

while.

And it was a wonderful, exciting feeling to see the world changing around us, to

see people opening up, becoming aware of themselves. When I taught belly

dancing, one of the things I wanted to make clear was that all the shapes and

forms are beautiful. That beauty is not one fixed shape, one fixed form. All

of them have their own beauty, and we should all have pride in that

beauty. That's the kind of freedom that I found important. Like, I shudder

today, to see teenagers trying to stuff themselves into somebody else's plastic

form, because then you never fit it, you never feel strong and you never feel

sure of yourself. But if you take the freedom of being what you are, and accept

that it is beautiful, then you become free. Then of course you have to

free others. But then I do have a Buddhist approach: "Sentient beings are

numberless / I vow to enlighten them all."

So: that's freedom.

[Q: The media frenzy around the Haight scene]

[LK, talking about the impact of the media’s coverage and commercialization of

Haight culture]: [inaud] was using people at that time. That's what newspapers

do, though. They do it now. They sell back to you whatever it was you did

yesterday, they sell to you on the front page. I don't know... It gave birth to

a lot of street theater. People would come and want to see it. They had bus

tours that would come into the Haight. And people would be staring at the

streets and people would be doing things on the streets. It was all very silly.

As far as, however, the things that were done, like the styles of clothing or

jewelry and stuff that was developed on the streets—that appeared in the big

store chains and was then sold in the middle of the country. Well, we were not

working as a commercial venture, so naturally we were pitted against such things

when they were developing a lot of 'em off us. Wwe would give it away, then

they'd take it home and manufacture it. This happens a lot. I guess I didn't

take it that seriously. There's always a lot more where it came from. [chuckles]

But the idea was completely antithetical to what we did, yeah.

But it also had some funny results with politics and corporations, because what

we were trying to do was help people be conscious. And I'm remembering

there was a very intelligent corporate man who came to visit me one day and he

ended up running down the stairs screaming because we were talking about

enlightenment and I was explaining that when I started sitting zazen, the idea

[is] you want to clear your mind. I sit there. My desire is to have a

clear mind and these things keep coming through, these thoughts and

remembrances, so I realize what I want is to clear it and all this is happening.

I am not my mind; I am something else. Now this is the trap of having a

fast mind, you know, if you don't tell the difference. Well, this man who is

very intelligent and very bright and all the rest of it, had gotten by on using

his mind, and the idea that there was something else terrified him so much

because the truth of it was undeniable —I mean you will come to that awakening

and there it is—that he ran screaming literally down the stairs and out of my

place because it affected him that strongly. Well, okay, this is a kind of

effect that telling the truth can have on anything founded on hypocrisy and

turning your vision away from reality.

So yeah, we ran into some differences there.

[Question about psychedelics and

enlightenment, spiritual work...]

That's an individual matter. You still gotta face yourself, whatever route you

want to take toward it. I mean, psychedelic drugs, taking LSD? Well, I don't

know. I mean, I had faced myself on peyote before I took LSD. And I just learned

that you can do whatever you have to do, no matter what condition you were in.

When I was at the Human Be-In at Golden Gate Park, which was a very huge, the

first big event, and I was on the stage, I was to read… When I’d walked into the

park, somebody had offered me some acid. And I looked at it and I thought, well,

if what I'm saying is true, then I'll be able to [be on acid and do the reading

at the same time]. And if it isn't, I better find out. So I took the acid,

dropped it, and I went up on stage. And did it. It was a strange day! [laughs]

But I did what I had to do, and I could speak my words. And I really [felt] like

if they weren't true that I should know that because I don't want to say

anything that isn't true. And I felt I could do it if they were. And I did. But

it was an interesting day... [laughs]

[And did you understand differently, your words?]

No, I understood them as I meant them. I mean, LSD didn't do that much to me. I

learned that I could do whatever I had to do in whatever situation. I keep

getting in situations. And they were often others to take care of. But it didn't

change my life, no. I mean, I'd already been involved in sitting zazen and stuff

like that. I'd already been doing a lot of interior searching and facing so it

wasn't a shock to me. People that lied to themselves about themselves got into a

lot of trouble with it. Personally, I think it's worth it because I wouldn't

want to live without knowing who I was, or hiding from myself. And unfortunately

a lot of people do. I don't think that's a solution to anything. I don't know

that psychedelics is a necessary part of it. For some people, it opened

up their lives; for some people, it didn't. I really feel it's an individual

matter there. I won't push for or against it. I had some fun with it, but... I

had found my revelations in other directions. That's personal, though.

[inaud query]

Well that comes back to 'say the truth,' really. I don't believe in messing

people over, I don't believe in doing things you don't want to do or not doing

things you do want to do. I don't believe in hurting people. I don't know..

"Revolution"? [laughs]

[discussion about language, words, concepts in different languages]

See, a poet, you work a poem, by what the words resonate with, what they make

you think of. It isn't just the word. There will be five words that mean pretty

much the same thing, but each of them has a different resonance. One will make

you think of soft summer days, one will make you think of classrooms — they're

the same word, but they've got these different tastes to them. So if you use

language, that way, you become very sensitive to it. So in other languages,

there are these different shades of meaning to words, some of them don't exist

in English. And I recognize that when there's a word that has all these other

meanings that I'd have to put on to it here. And like the concepts were too

small. I mean, we don't have a word that comes gently, softly, sweetly. At once.

It's, you know, when I see like, I can think the way a dandelion lands. You

know, with a parachute, this dandelion flower goes up, and then it lands that

way. I mean, it can't land any other way but 'softly' and there's a connotation

that I can find in there, that I can't find another word here. And I noticed

that's one of the reasons I like to play with language. Because I really feel

like it shapes the way we think. If we had more words for pleasure it might be a

good idea. [laughs]

[inaud about poets being able to use words…?]

Aha, well, actually, maybe just connect them differently. Bring them out. I

can't do it to anyone or for anyone. But I can maybe help people think in those

directions. And the things that we did in the Diggers were definitely a lot of

street theater, saw a lot of an accidental but you know, it was a whole bunch of

very creative people very busily interacting, so a lot of things would happen.

And mainly the idea was just: Wake up.

[Q: Why do you think there were so many talented people in the same place at the

same time?]

Well, that is partly San Francisco. A lot of people came here from other places.

It was just the right time, you do. I don't know. It was the right time. I mean,

things were happening in Hollywood [too]. We were doing a lot of things.

Creative people do tend to herd together every now and then. And when you get

that much going on, there’s sparks—a lot of sparks.

[Q about Diggers drifting apart]

It's surprising how many of us are still in touch, and affect each other's lives

all the time. I'm going on spreading the same thing. Vicki with the children's

book project, I think it's wonderful. Peter's all over the world doing things,

Peter Berg. Everybody's still doing whatever it was they were doing. Nobody was

lying. There have been those who have fallen by the wayside. But that's

from, you know, what's happened with life, not from a change of feeling. I think

it's rather interesting that so many of us continue after such a long time.

If it weren't for my friends, it would be a different world. Not as good. It'll

get better. It's your turn.

[chuckles] I've lived by it all my life. In fact, one of my aliases was [Sara N

Dipity?], which was serendipity. I play word games. Like I said, Sir, I depend

on it. [laughs] If you clear yourself and you follow, the right things will

happen. You'll be in the right place at the right time. But you’ve got to be

clear with yourself—you have to be honest with yourself, before you can

be honest with anyone else. First, you face yourself.

[What is the place where

things are happening now?]

For me, right here. [chuckles] I haven't even thought about that. I mean, it's

time to for it to be happening everywhere in the world. As one. We have to

function as a whole. We are the same. We're people. [points at cat] And there's

people with furry faces and tails. Like there's a little one that's running

around there. We're beings, we're the fruit of stars. We're connected. I mean,

what's happening with discovering other universes fascinates me. The

possibilities of really finding more about, finding others, I think it's

wonderful. How can you possibly go around having these stupid wars when there's

these other things that are so much more interesting? One of my predilections

when I'm thinking about things is standing on the shores of infinity, and trying

to look just beyond it — thinking of time and, without time, trying to look

around the edges of time. What's right next to it? What's "beginning" mean?

There's frontiers that are much more interesting than national borders. So, yes,

I would love to travel. But I don't think I would really feel totally alien

anywhere I can think of. If I couldn't think of it, I might feel alien

there…

[Returning to the question] I don't know where "it" is happening. It is

happening wherever it wants to. It could be happening everywhere. I mean, "it"

is usually the intersection of more than one mind that freely plays with

another. It does require a certain amount of trust but I think that can happen

absolutely anywhere, anytime. All you have to do is really let your mind go,

trust another being, see what happens. Could be interesting. Well, I wish that

would influence politics. Phew. Can you imagine what politics would be like if

somebody trusted somebody else? It would [inaud].

[Question about being at the center of things]

Well, we were a center. And all we wanted to do was change the world. And

we did change quite a lot, actually. Certainly left some effects. They're all

seeds. That's all you can really leave, the seeds. And they'll all sprout and

turn into something you would have never imagined! And better than you would

imagine, I hope. I wish we'd had a little bit more influence. I sure don't like

what's happening now, I don't like all the unhappiness. It's a hell of a world

to have to be growing up in, there's so many restrictions that have been caused

by human beings... Look at what's happened to sex... I feel really sorry for

kids growing up—they can have no true freedoms, sexually. I mean, you're in

danger of your life. I can't stand it seeing people die from AIDS.

But we're also doing some incredible things, like I said, seeing other universes

and stuff. I guess it's just different each time around. This time, I don't know

where "it" is, except anywhere. Ah! That's was right, that's one of my poems,

come think of it! "Locate the center of infinity/Answer: anywhere." [chuckles]

That's true.

It's a dangerous thing, always, to form an image of somebody

before you know them. Especially with me, because I'm just me, you know, I mean,

exuberantly me, extremely me. And I don't do well with fantasies. I'm not formal

enough for a fantasy.

[Q regarding Diggers reconnecting?]

We're all still, there's these funny connections. If you're connected, I don't

think you ever get unconnected. But I remember like, Jane [Lapiner] came down

and did something and I had just written a poem that was about the same thing

she was doing. We're all still thinking in a lot of the same terms.

Unfortunately, I don't get out. So I’ve missed a whole lot of these things.

[Q: How do you regard that era, compared to now…]

I feel very lucky. I really truly do. I feel very lucky for having lived at that

time, for having had that. It was wonderful. The largest difference I can feel

between then and now is we were full of hope and expectation. And I don't feel

that around me anymore as a general drift. There's a lot of hope to just get by,

or negative expectation. We really felt the change for the better was not only

possible but within our grasp, and that we were helping it be born. Living with

such positive energy all around you, or being part of... I mean, we gave an

incredible amount to it, but we got an incredible amount, and I truly

feel, you know, blessed and lucky that I had that time. And everyone who was

into that, not just us that were really active in it, but people who just got

brushed by it—a newsman on a television [recently], I saw his face when he said

something about the ‘60s and it melted suddenly soft and loving. I mean he had a

good time then too, and it's obviously a shining memory of his life. So it was a

wonderful time. I wish that that energy could be born again. It's going to be

pretty tough, though. Life and death times are a lot harder right now— and I

guess it always is — but I don't see the expectation and hope around now that I

did then. Course, I'm not working hard enough at it, maybe..? There's that too,

right?

[Q: You think that, but…]

I do. But I don't see it [change] as a general experience of every hour of every

day, for every being. There was a whole lot of it spread around in the '60s — it

was much easier to grasp. You gotta fight for it now.

[Q: Yeah, but it was just for a little while…]

If it happens once [is a big deal]. Look what religions rely on: one

incident, picked up, magnified, repeated, proliferates — and the world

changes. It comes back again to consciousness. If you're conscious, if you

take responsibility for yourself, [then] there's an infinitude of hope. You can

change the world — you can change anything.

I get pissed at myself, because of all these physical difficulties. At the same

time, I really am sure that if I concentrate on it, on nothing else but that, I

could change it. But I get bored with trying to fix my body.

So there's still hope out there, I'm not saying there's not hope. But it's a

different — every ten years at least, it's a different turn. And there's some

pretty difficult turns right now. And I feel real lucky that I hit that one, in

the ‘60s. Because it was so much fun. I mean, there's nothing I can think

of that could be more fun than spreading freedom, spreading joy. We did a lot of

that. And it left, you know, changes that are going on from there. Right? I

guess AIDS bothers me a lot. It's changed so many lives. And there's so much

pain. Pain bothers me. I don't like to see people hurt, unnecessarily. Certain

things are necessary, but... It's not that I feel hope is gone, but the favored

directions that people are casting about in right now are not as positive as we

had. There's a lot of negativity I see out in the world.

[Q: In the 70s, how did you feel, what did you feel]

The 70s and 60s kind of blended. [impatient] You can't ask me things about

specific dates. [laughs] You can ask me but I can't answer them.

[Q: People left San Francisco…]

It wasn't a center that was bursting with energy. However: there are little

centers all over. I mean, there are still some here. The people that went out to

do different things, tried different ways. When I said things are seeds, a seed

pod, when it's ripe, explodes seeds all over the place. Some of them change,

some of them are very similar, but then you know, you've got to have different

ways. And all these people who scattered out there, still hold on. There's an

amazing amount of understanding, of... teaching. The only true way you can teach

is by example. What you say isn't what counts. Which is what

started things in the 60s, people suddenly realizing everything their parents

told them was something their parents said, but didn't live by. And this,

you know, it's a great gap.

[inaud Q]

Well, people were trying to learn to say what they meant — to live by what they

said. And spread that. And there is a lot of that, all around, where all these

things have fallen… It’s not as hot and heavy as it was when it was one

pulsating group, when things were happening all the time out of it.

[End]

—posted 2024-03-09