|

| |

(Illustrated and Annotated)

The (English) Digger Writings

A chronological index to the publications, treatises, manifestos, and

letters of Gerrard Winstanley and the

Diggers, 1648-1652

The writings of Gerrard Winstanley

inspired the Digger movement in England in 1649, as well as the San

Francisco Diggers in 1966. Emmett Grogan quoted Winstanley in

Ringolevio: ""No other

matter herein, but to observe the Law of righteous action, endeavoring to

shut out of the Creation, the cursed thing, called Particular propriety,

which is the cause of all wars, blood-shed, crime, and enslaving Laws, that

hold the people under miserie." That is a quote from the English Diggers' second

manifesto, and Grogan called it "stone idealism."

Winstanley was first and foremost a

seeker whose religious and political ideas came from personal revelations

that he reported in the first five of his writings (known collectively as

his "theological treatises"). In a trance, he heard the command, "Worke

together. Eat bread together; declare this all abroad." Within months, a

small band of believers set upon the common waste lands on St. George's Hill

in Surrey, and began cultivating crops together. Over the next year,

Winstanley and this group would produce a dozen manifestos and letters

explaining their beliefs. They would move their community a few miles away

after being driven from the original site, and eventually disbanded under

intense physical and legal harassment. Winstanley's final writing two years

later was his detailed outline for a commonwealth based on the ideals the

Diggers had attempted to implement.

The following is an

index of the writings here:

-

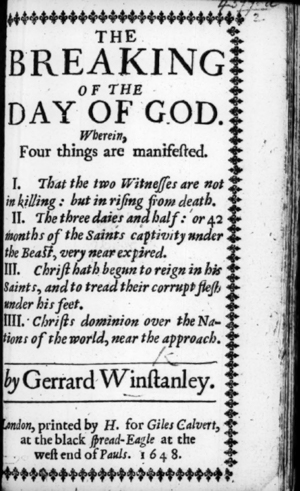

The Breaking of the Day of

God, 1648

-

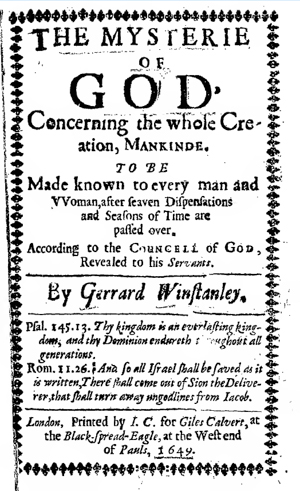

The Mysterie of God, 1648

-

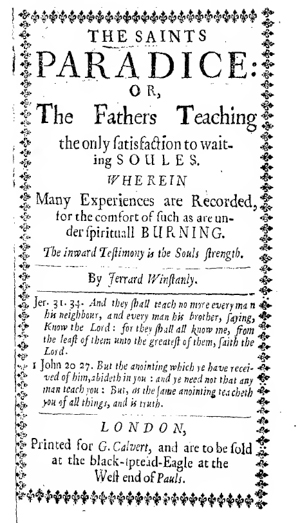

The Saints Paradise, 1648

-

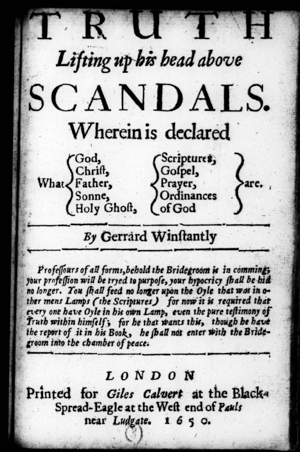

Truth Lifting up his head

above Scandals, 1649

-

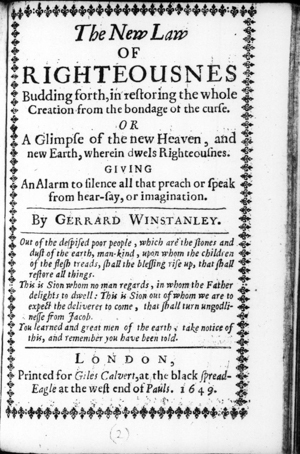

The New Law of Righteousnes,

1649

-

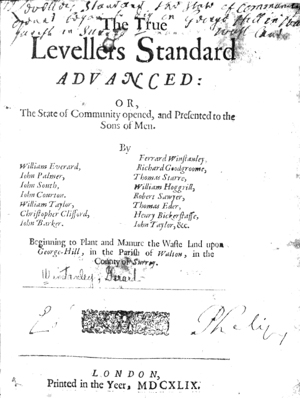

The True Levellers Standard

Advanced [aka A Declaration to the Powers of England], 1649

-

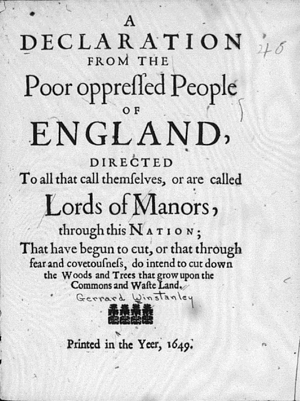

A Declaration from the Poor

Oppressed People of England, 1649

-

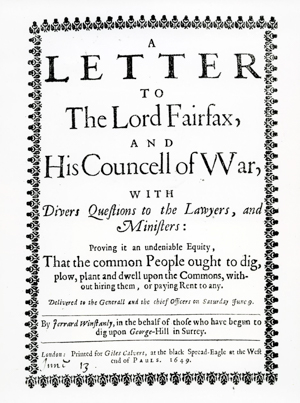

A Letter to the Lord Fairfax,

and his Councell of War, 1649

-

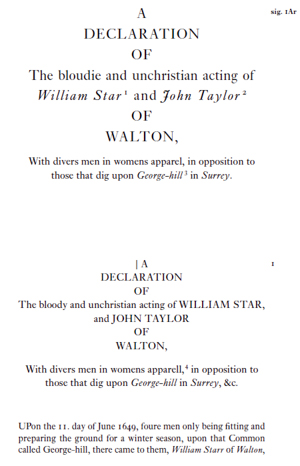

A Declaration of the Bloudie

and Unchristian Acting of William Star and John Taylor, 1649

-

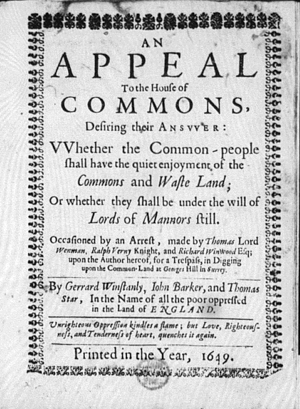

An Appeal to the House of

Commons, 1649

-

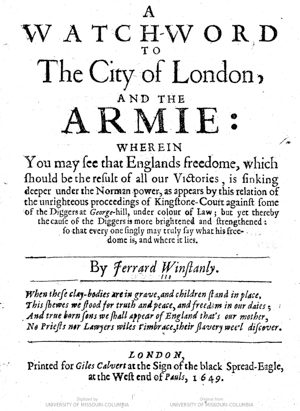

A Watch-word to the City of

London, and the Armie, 1649

-

Two Letters to Lord Fairfax,

1649

-

A New-yeers Gift for the

Parliament and Armie, 1650

-

Englands Spirit Unfoulded. Or

an Incouragemment to Take the Engagement, 1650 [not included here]

-

Fire in the Bush, 1650

-

Vindication of those, whose

Endeavors is Only to Make the Earth a Common Treasury, Called Diggers,

1650

-

An Appeale to All Englishmen,

1650

-

A Letter taken at

Wellingborough, 1650 [not included]

-

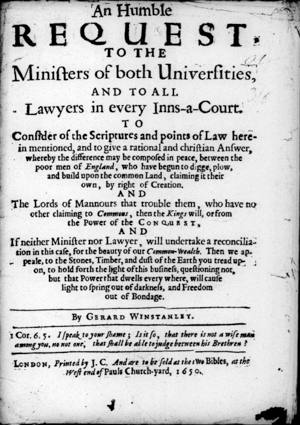

An Humble Request to the

Ministers of both Universities, and to All Lawyers in Every

Inns-a-Court, 1650

-

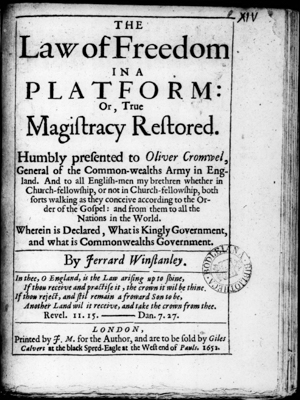

The Law of Freedom in a

Platform, 1652

-

Other Works Connected with

the Diggers

|

To view a full-size version of any image, click once to enlarge it, then click

again to return to the smaller version.

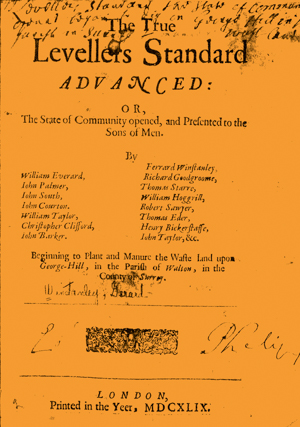

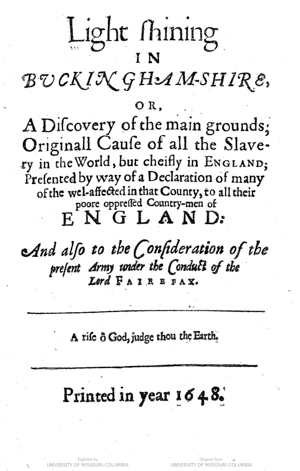

The True Levellers Standard Advanced (known as the

first Digger manifesto), 1649

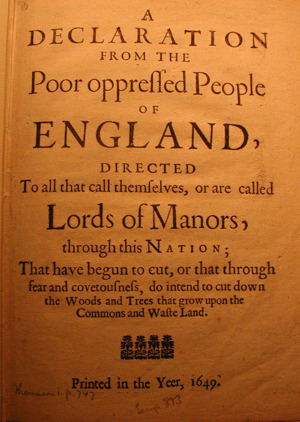

A Declaration from the Poor oppressed People of England (known as the

second Digger manifesto), 1649.

The following texts have links to a full-text transcription (from the University

of Michigan or other sites), and, where available, a PDF scan of the original

publication.

|

| Written less than a

year before the first Digger commune at St. George’s Hill, The Breaking

of the Day of God lays the spiritual groundwork for Winstanley’s later

activism. He proclaims that the reign of corrupt worldly powers—“the

Beast”—is nearing its end, and that Christ has begun to rise not in the

heavens, but within the hearts of the poor and despised. The inward reign of

Christ, Winstanley argues, will soon manifest outwardly in a new

commonwealth governed by righteousness, peace, and mutual care. The

transformation he anticipates is not merely mystical—it is social and

political, foreshadowing the Diggers' call to abolish private property,

overturn hierarchical power, and cultivate the earth in common.

"All the oppression, injustice, false shewes and formes of Gods Worship,

shall all be destroyed in the World, and judgement shall run down our

streets like a stream, and righteousnes like a River."

Links:

University of Michigan Library (Full

text).

The original 1648 publication (Scan

as PDF).

|

|

|

The Saints Paradice (1648) is a

foundational text in the development of Winstanley's radical theology. Here,

he articulates the inward-turning revelation that each person carries the

divine Spirit within themselves and that true knowledge of God comes not

from scriptures or external authorities but from inner experience and

spiritual obedience. This deeply personal account of spiritual awakening

anticipates the core principles of the Digger movement — especially the

belief in direct access to divine truth, the rejection of social and

religious hierarchies, and the vision of a community governed by divine

reason and justice.

"[I]f you subject your flesh to this mighty governour, the spirit of

righteousnesse within your selves, he will bring you into community with the

whole Globe, so that in time you shall come to know as you are known, and

you shall not need to run after others, to learn of them what God is, for as

you are a perfect creation, every one of himself; so you shall see, and feel

that this spirit is the great governour in you, in righteousnesse; and when

you come thus to know the truth, the truth shall make you free from the

bondage of covetous, and proud flesh, the Serpent that holds you under

slavery all your life time."

Links:

University of Michigan Library (Full

text).

The original 1648 publication (Scan

as PDF).

|

|

|

Winstanley

argues that divine truth resides not in external scriptures or priestly

authority, but within each person as "Reason"—a living, spiritual force that

manifests as justice, peace, and communal harmony. He rejects the legitimacy

of university-trained ministers, institutional religion, and secondhand

faith based on “tradition,” advocating instead for direct spiritual

knowledge through the inner light of Reason. This argument frames the

spiritual rebellion that underpins Winstanley’s later calls for economic and

social transformation. By equating divine truth with communal Reason and

aligning salvation with righteous action, Winstanley sets the groundwork for

the Diggers’ radical vision: the abolition of private property, the

cultivation of land in common, and the creation of a society based on

justice and equality.

"When a man lives in all acts of love to

his fellow-creatures; feeding the hungry; clothing the naked; relieving the

oppressed; seeking the preservation of others as well as himself; ...

to this end, that the Creation may be upheld and kept together by the spirit

of love, tendernes and one-nesse, and that no creature may complaine of any

act of unrighteousnesse and oppression from him."

Links:

University of Michigan Library (Full

text).

The original 1649 publication (Scan

as PDF).

|

|

|

Winstanley

argues that all of humanity is God's creation and that God intends

ultimately to redeem all people, not just a chosen few. He identifies the

root of sin and social corruption as "selfishness"—a Serpent-like power that

leads individuals to assert a being separate from God. This selfish spirit

must be overcome not by human striving but through divine action, which will

unfold across seven dispensations of history. Winstanley insists that God's

final purpose is to dwell within every person and restore all of creation to

unity and righteousness. In this vision, “the Serpent” (self-will, pride,

and oppressive power) is cast out, while humanity—the divine garden—is

renewed. This theology presages the Diggers' belief in economic equality,

communal land ownership, and the possibility of a just society rooted in

divine reason rather than hierarchical authority.

"Now the mystery of God is this, hee will destroy and subdue this power

of darknesse, under the feet of the whole Creation, Mankinde, and every

particular branch, Man and Woman, deliver him from this bondage and prison,

... so that the wisdome, power, love, life, beauty, and Spirit of truth that

dwels and rules in Man, may be God himselfe."

Links:

University of Michigan Library (Full

text).

The original 1649 publication (Scan

as PDF).

|

|

|

Here,

Winstanley lays the spiritual and ideological foundation for the Digger

movement. He proclaims the imminent restoration of the world through the

divine “Law of Righteousness,” a spiritual principle that seeks to liberate

creation from bondage and return humanity to a state of peace, equality, and

justice. He describes this as a world in which selfishness, private

ownership, and hierarchical rule give way to communal living and mutual aid.

His appeal to “the poor despised people” as the true agents of divine

restoration fueled the Diggers’ action to cultivate common land and reject

private property. The idea that “the Earth [is] a Common Treasury” and the

emphasis on abolishing class hierarchies and economic oppression grew

directly from this text.

"And let all men say what they will, so long as such are Rulers as cals

the Land theirs, upholding this particular propriety of Mine and Thine; the

common-people shall never have their liberty, nor the Land ever freed from

troubles, oppressions and complainings; by reason whereof the Creatour of

all things is continually provoked. ... AS I was in a trance not long since,

divers matters were present to my sight... Likewise I heard these words,

Worke together. Eat bread together; declare this all abroad."

Links:

University of Michigan Library (Full

text).

The original 1649 publication (Scan

as PDF).

|

|

|

The True Levellers Standard Advanced, issued in April 1649 and signed

by Gerrard Winstanley and other early Diggers, is the foundational manifesto

of the English Digger movement. It was a public declaration to the

government and the world explaining why they had begun cultivating common

land at George Hill in Surrey. The Diggers believed that the Earth was

originally created as a “common treasury” for all living beings, and that

private property—especially land ownership—was an artificial and unjust

invention that led to inequality, oppression, and violence.

This text is the Diggers’ core political and

spiritual manifesto, presenting a theological and moral argument for

reclaiming and sharing the land. It publicly declared their actions as a

direct challenge to economic inequality and religious hypocrisy, framing

their movement as a prophetic call for justice and divine harmony.

Introducing key Digger themes—land as common, equality as divine law, and

rejection of landlordism—it inspired future communal movements by affirming

the poor’s right to resist oppression through collective labor and action.

"There shall be no buying nor selling, no fairs nor markets, but the

whole earth shall be a common treasury for every man, for the earth is the

Lords. And man kind thus drawn up to live and act in the Law of love, equity

and onenesse, is but the great house wherein the Lord himself dwels, and

every particular one a severall mansion: and as one spirit of righteousnesse

is common to all, so the earth and the blessings of the earth shall be

common to all; for now all is but the Lord, and the Lord is all in all."

Links:

Luminarium Renascence Editions (Full

text).

The original 1649 publication (Scan

as PDF).

|

|

|

This is the second Digger manifesto,

from June 1649, two months after the first manifesto. Signed by Gerrard

Winstanley and other early Diggers, it calls for the common ownership of

land and resources. Addressed to the “Lords of Manors,” it denounces private

property and land enclosures as theft and oppression rooted in violence and

conquest—specifically the legacy of the “Norman Yoke.” The signers of the

manifesto declare that the Earth was made by God to be held in common, not

hoarded by the few. They claim a divine and natural right to dig and

cultivate the commons, asserting that their peaceful labor is a righteous

act in accordance with divine justice and creation itself. They reject the

authority of buying and selling, associating money with the biblical “mark

of the Beast,” and condemn all systems that reduce people to beggars while

privileging landlords and merchants. The Declaration demands the use of

common woods and lands to sustain the poor and lays out a moral and

theological justification for their communal actions. "The

Earth, with all her Fruits of Corn, Cattle, and such like, was made to be a

common Store-house of Livelihood to all Mankinde, friend, and foe, without

exception. And ... know this, That we must neither buy nor sell; Money must

not any longer (after our work of the Earths community is advanced) be the

great god, that hedges in some, and hedges out others; for Money is but part

of the Earth: And surely, the Righteous Creator, who is King, did never

ordain, That unless some of Mankinde, do bring that Mineral (Silver and

Gold) in their hands, to others of their own kinde, that they should neither

be fed, nor be clothed."

Links:

University of Michigan Library (Full

text).

The original 1649 publication (Scan

as PDF).

|

|

|

Winstanley delivered

this letter on June 9, 1649, to the commander of the Parliamentary army to

defend the Diggers’ occupation and cultivation of common land at St.

George's Hill in Surrey. Fairfax visited the Diggers after he received

complaints from local landowners. Winstanley emphasizes that their digging

is peaceful and righteous, aimed at relieving poverty and ending economic

oppression. He refutes accusations that the Diggers are seeking to fortify

themselves or incite violence, instead casting their efforts as part of a

cosmic struggle between good and evil — “the Lamb and the Dragon.” They do

not seek protection from Fairfax but feel compelled to bear witness to a

higher law of justice and creation. Winstanley also asserts that true

liberty cannot coexist with private property and hierarchical rule. He

concludes by challenging the legitimacy of Norman land tenure and to argue

that the English people — especially the poor — have a lawful right to

cultivate the commons. "When you were at our Works upon the

Hill, we told you, many of the Countrey-people that were offended at first,

begin now to be moderate, and to see righteousnesse in our work, and to own

it, excepting one or two covetous Free-holders, that would have all the

Commons to themselves, and that would uphold the Norman Tyranny over us,

which by the victorie that you have got over the Norman Successor, is

plucked up by the roots, therefore ought to be cast away."

Links:

University of Michigan Library (Full

text).

|

|

| This pamphlet,

published in defense of the Diggers' efforts at St. George’s Hill, denounces

a brutal attack on June 11, 1649, against four peaceful Diggers by William

Starr and John Taylor of Walton, along with several disguised men in women’s

clothing. The assailants beat the Diggers severely with clubs, leaving one

near death. The Diggers, who had been tilling common land nonviolently,

refused to fight back and instead placed their trust in divine justice. The

author contrasts the attackers’ violent actions—deemed unchristian and

beastly—with the Diggers’ patient, godly resolve. "Love suffers

under thy furie, love suffers under thy hypocrisie, under thy pride,

carelesse, covetous, hard-hearted, self-seeking children. Love bears all

things patiently, he suffers thee to reproach, to fight, to oppose, and to

rejoyce in doing those things."

Links:

University of Michigan Library (Full

text).

|

|

|

This is a direct

plea to Parliament from Winstanley and fellow Diggers, written in 1649 after

their arrest for digging and planting on common land at St. George's Hill.

They ask the House of Commons to clarify whether poor people will be allowed

to peacefully cultivate and benefit from the commons and waste lands, or

whether they will remain subject to the oppressive control of lords of

manors. The appeal argues that the English people, especially the poor,

fought and sacrificed during the Civil War with the promise of a new, just

order. Winstanley contends that the common people have an equal right to the

land by both divine creation and by right of conquest, having helped

overthrow the king. Continuing to enforce the old Norman land laws (which

were imposed by conquest and favor the aristocracy) breaks the Covenant made

between Parliament and the people.

"Therefore seeing we have with joynt consent of purse and person

conquered his successor, Charls, and the power now is in your hand, the

Nations Representative; O let the first thing you do, be this, to set the

land free. Let the Gentry have their inclosures free from all Norman

enslaving intanglements whatsoever, and let the common people have their

Commons and waste lands set free to them, from all Norman enslaving Lords of

Mannors..."

Links:

University of Michigan Library (Full

text).

The original 1649 publication (Scan

as PDF).

|

|

|

Written in late

summer 1649, Winstanley’s pamphlet is a direct and impassioned address to

the City of London and the New Model Army, warning that England’s promised

freedom after the Civil War is being betrayed. Despite the abolition of the

monarchy and the proclamation of a commonwealth, he argues that true liberty

is being subverted by the continued dominance of the “Norman power” — a

system of land ownership, legal privilege, and social hierarchy inherited

from William the Conqueror. He recounts the legal persecution he and other

Diggers faced for cultivating common land at St. George’s Hill. Denied the

right to defend themselves in court without paying lawyers, they were

punished under unjust laws that favored landlords and freeholders — the very

classes who had profited from the old kingly system.

"Therefore we justifie our act of digging upon that hill, to make the

earth a common treasurie. First, because the earth was made by Almighty God,

to be a common treasury of livelihood for whole mankind in all his branches,

without respect of persons; and that not any one according to the Word of

God (which is love) the pure Law of righteousnesse, ought to be Lord or

landlord over another..."

Links:

HathiTrust Digital Library (Full

text).

The original 1649 publication (Scan

as PDF).

|

|

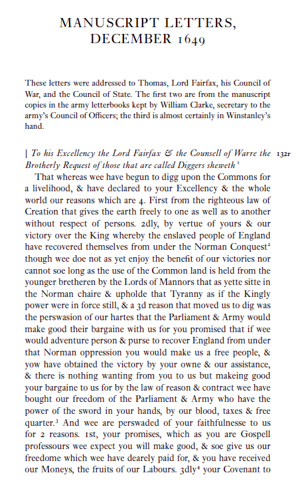

| A series of three

manuscript letters written in December 1649, to Lord Fairfax, the Council of

War, and the Council of State, with impassioned appeals from the Diggers (or

True Levellers), asserting their right to cultivate common land and

condemning renewed oppression by manorial lords and soldiers. They present

both moral and political arguments for land reform, rooted in scripture,

natural law, and the supposed contract between the Parliament/Army and the

people. "Now Sir, the end of our digging & ploughing upon the

common land is this, that wee & all the impoverisht poore in the land may

gett a comfortable livelyhood by our righteous labours thereupon, which we

conceive wee have a true right unto (I speake in the name of all the poore

commoners) by virtue of the conquest over the King, for while hee was in

power hee was the successour over William the Conquerour & held the land as

a conquerour from us, & all Lords of Mannors held tytle to the common lands

from him, but seeing the common people of England by joynt consent of person

& purse, have cast out Charles our Norman oppressour wee have by this

victory recovered ourselves from under this Norman yoake, & the land now is

to returne into the joynt hands of those who have conquered, that is the

commonours, & the land is to bee held noe longer from the use of them,..."

Links:

Sabine transcription of two of the manuscript letters (Scan

as PDF).

|

|

|

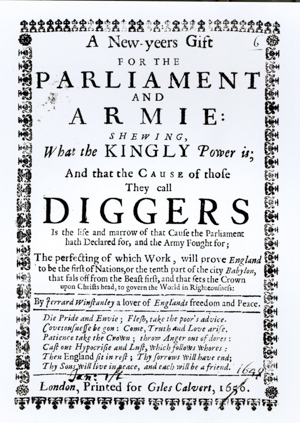

Printed ca.

January 1, 1650. This lengthy essay by Winstanley addresses Parliament and

the Army, urging them to fulfill their promises of abolishing

Kingly Power and establishing a

true Commonwealth. He distinguishes

between two forms of kingly power: the divine power of righteousness (God’s

universal love) and the oppressive power of self-interest and conquest,

which he associates with the Devil, conquest by William the Conqueror, and

the remnants of feudalism. Winstanley argues that the poor who supported the

Parliament’s struggle against the monarchy now suffer under continued

oppression from landlords, Lords of Manors, clergy, corrupt judges, and

lawyers—all branches of the same tyrannical "kingly" structure. He calls on

rulers to honor their commitments by redistributing common and waste land to

the poor, who are entitled to it by natural law, labor, and shared sacrifice

during the civil war.

"You shall see by and by, That our principles are wholly against Kingly

power in every one, as well as in one. Likewise we hear, that they told you,

that the Diggers do steal and rob from others. This likewise is a slander:

we have things stollen from us; but if any can prove that any of us do steal

any mans proper goods, as Sheep, Geese, Pigs, as they say, let such be made

a spectacle to all the world: For my part, I own no such doing, neither do I

know any such thing by any of the Diggers."Links:

University of Michigan Library (Full

text).

|

|

|

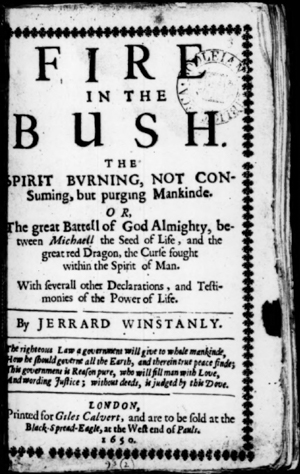

Fire in the Bush

(1650) is a restatement by Winstanley of themes from his earlier

religious tracts, calling for spiritual renewal and social

transformation grounded in universal love, reason, and the rejection of

private property. He describes an inner battle between two powers in the

human heart: the Serpent (self-love, hypocrisy, and imagination) and the

Seed of Life (universal love, reason, and equity). Winstanley urges

readers to reject outward religion, private property, and coercive

government—symbols of the “four Beasts” of tyranny—and instead embrace

the inner Christ, the Tree of Life, whose reign brings peace, justice,

and communal harmony. True freedom, he insists, begins within and leads

to the restoration of the earth as a common treasury for all.

"For in the midst of this Garden likewise, there is the Tree of Life,

who is this blessing, or restoring power, called universall Love, or

pure knowledge, which when mankinde by experience begins to eat thereof,

or to delight himselfe herein, preferring this Kingdome and Law within,

which is Christ, before the Kingdome and Law, that lies in objects

without, which is the devill..."

Links:

University of Michigan Library (Full

text).

The original 1650 publication (Scan

as PDF).

|

|

|

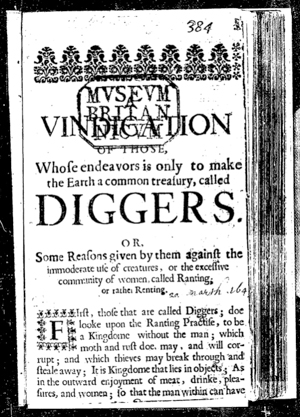

Vindication

(1650) was published concurrently with Fire in the Bush, perhaps as a

coda as Thomas Corns (et al.) suggest. Here, Winstanley defends the Diggers

and distinguishes their project of communal land ownership and righteous

living from the behavior of the Ranters, whom he criticizes for excessive

indulgence in sensual pleasures, especially sexual promiscuity and idleness.

He argues that such behavior is not part of the Digger vision but rather a

destructive and irrational force driven by lust and the senses, which he

calls the “King Lust” or the “Ranting power.” Winstanley calls on people to

reform themselves through righteous labor—digging and cultivating the

commons—and to suppress sin through inner reason, not external punishment.

He emphasizes that the kingdom of God is within and that true peace comes

from living modestly, rationally, and communally, not from indulging in the

desires of the flesh. This pamphlet was published co

"Would thou live in peace; Then look to thy own wayes, mind thy owne

Kingdome within, trouble not at the unrational government of other mens

kingdomes without; Let every one alone, to stand and fall to their owne

Master for thou being a sinner, and strives to suppresse sinners by force,

thou wilt thereby but increase their rage, and thy owne trouble: but do thou

keep close to the Law of righteous reason, and thou shalt presently see a

returne of the Ranters: for that spirit within must shame them, and turne

them, and pull them out of darknesse."Links:

University of Michigan Library (Full

text SEE BOTTOM OF PAGE BELOW HEADING).

|

|

|

This 1650 broadside—the

only known publication by the Diggers in that format—was issued after they

had relocated from St. George’s Hill to nearby Cobham. It is a passionate

appeal for public support of their ongoing experiment in common cultivation.

The text argues that, with the overthrow of monarchy and the defeat of the

“Norman yoke” through civil war, the English people are now entitled to

reclaim the land as a “common treasury” for all. Drawing on both Scripture

and recent acts of Parliament, the Diggers claim legal and spiritual

justification for their efforts to cultivate common land for the benefit of

the poor. They sharply denounce the lingering power of manorial lords and

clergy who hoard wealth and obstruct access to the means of subsistence.

"Behold, behold, all English-men, the Land of England now is your free

Inheritance: all Kingly and Lordly entanglements are declared against, by

our Army and Parliament. The Norman power is beaten in the field, and his

head is cut off. And that oppressing Conquest that hath raigned over you by

King and House of Lords, for about 600. yeares past, is now cast out, by the

Armies Swords, the Parliaments Acts and Lawes, and the Commonwealths

Engagement."

Links:

University of Michigan Library (Full

text).

|

|

|

This 1650

pamphlet is Winstanley’s direct appeal to the ministers of the universities

and lawyers of the Inns of Court to consider, scripturally and legally, the

legitimacy of the Diggers’ claim to cultivate common land. Framed as a

reasoned and Christian inquiry, it defends the Diggers' actions at Cobham

based on the "right of creation"—that the earth was made by God to be a

common treasury for all. Winstanley argues that lords of manors base their

authority solely on Norman conquest and kingly power, which have been

repudiated by the new Commonwealth. He cites numerous scriptural passages to

support the idea that land should be held in common and that enclosure and

domination by landlords represent a fall from divine law into sin, violence,

and bondage. He positions the Diggers as faithful Christians enacting God’s

restorative justice, and contrasts their peaceful labor with the violent

suppression they faced—most notably from Parson John Platt and other gentry,

who burned their homes and assaulted their families.

"Yet the Gentry and Lords of Mannors, who are part of the Kingly and Lordly

Power, they have met divers times in Troops, and have beaten and abused the

Diggers, and pull’d down their houses. Yet we do not heare that the Clergy,

Lawyers, or Justices, who would be counted the dispensers of righteous

justice, do speak against them for Rioters, but against the poor labouring

men still, checking the Labourers for idleness, and protecting the Gentry

that never work at all..."Links:

University of Michigan Library (Full

text).

The original 1650 publication (Scan

as PDF).

|

|

|

The Law of Freedom (1652) was

Winstanley's final political treatise. He addressed it to Oliver Cromwell,

the Lord General of the Parliamentary Army. By the time of its publication,

the Digger movement had been forcibly suppressed, and Winstanley had shifted

away from direct political activism. This work represents his most complete

and systematic vision for a post-monarchical commonwealth—a society without

private property, class hierarchy, or economic exploitation. Although

Winstanley lived into the 1670s, he did not publish any further political

tracts after this one. The Law of

Freedom stands as the culmination of his revolutionary thought, and

represents a detailed outline for a commonwealth based on the ideas that

first motivated the Diggers: common ownership of land (Earth as a common

treasury), abolition of buying and selling, guaranteed access to food,

shelter, and clothing, no landlords, no masters, no clergy living off

tithes, local self-governance and representative democracy, peace and

justice.

"The Earth shall be planted, and the fruits reaped, and carried into

Store-houses by common assistance of every Family: The riches of the

Store-houses shall be the Common Stock to every Family: There shall be no

idle person nor Begger in the Land."Links:

University of Michigan Library (Full

text).

The original 1650 publication (Scan

as PDF).

|

|

Miscellaneous Publications

|

|

Both Sabine and Corns (et al.) have a few miscellaneous publications

that I will eventually scan and put here. For now, refer to those books for

more information.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

![High-Res Image]()

[Last edit: 2025-07-09]

|