|

| |

A Brief History of the San Francisco Diggers

(and the movement they spawned)

Index to this section:

Ben Kinmont asked me to write a short history of the Diggers for a

Free art happening he was planning called "Our Commons Are Free"

which he staged in May 2022 at a Santa Rosa (California) park. Ben was

intrigued by the underground publishing ventures that the Diggers

inspired — starting with the early Digger Papers, followed by the

Communication Company, the Free City News, the Free Print Shop, and the

intercommunal free newspaper, Kaliflower.

In the first iteration of Ben's extravaganza, he (with a group of

volunteers) replicated the instant publishing

tradition of the

Communication Company. The first edition of this history was printed

and distributed free to passersby in the Santa Rosa park. Ben subsequently took an expanded

version of "Our Commons Are Free" to Italy in September 2022 (with the

addition of Digger Bread baking and Digger videos). An even extended

version is planned for Paris in April 2023.

Ben maintains a

page with the

different editions of this text published for free by his Antinomian Press.

Attached

here is a PDF of the version of this text that Ben is taking to

Paris. It includes an introduction by Ben on his personal journey which

brought him to this moment. It is interesting to note that his life path

had connected at several points with both the San Francisco Diggers and

the 17th Century English Diggers before he jumped headlong into this

project.

Note: all images are "clickable" to view higher resolution versions.

|

|

Radical social

movements can have their roots decades, and even centuries, in the past;

likewise, they can leave their traces deep into the future. This is the

story of the roots and traces of one such radical movement.

|

|

|

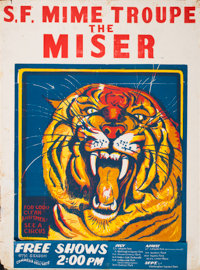

One of the most important influences on the San Francisco Diggers was R.G.

"Ronnie" Davis, the founder and consummate theoretician of the San Francisco

Mime Troupe. The experiences that many of the original Diggers took from

their involvement with the Mime Troupe were the foundation for the idea of

"life acting" in the service of social change. In his 1966 essay “Guerilla

Theatre," Davis called for theater collectives to "teach / direct toward

change / be an example of change." In a nutshell, this is the definition of

'lifestyle as change agent'—the contribution of the Sixties Counterculture

to social protest history. Later feminist theory would propose "the personal

is the political"—a slight reformulation of Davis' concept of guerrilla

theatre.

See also:

|

|

|

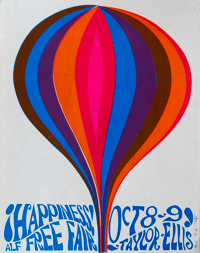

The Mime Troupe was arrested at a publicly staged event in August 1965

after their permit to perform in the parks was revoked by the San Francisco

Recreation and Parks Commission for alleged obscenity. The resulting events

to support the troupe galvanized the new hip community of artists and social

outcasts. At a symposium where Ronnie Davis lambasted the Establishment,

longtime radical poet and gadfly Kenneth Rexroth gave a speech that would

inspire the formation of the Artists Liberation Front, a group of working

artists who planned a series of Free Fairs in the fall of 1966. The ideas

behind the Free Fairs and the Artists Liberation Front (ALF) are

significant. They represented the first stirrings of the neighborhood arts

movement. Their influence on the San Francisco counterculture then emerging

was profound. The Free Fairs became the first joyous outdoor communal

celebrations, one of the most important symbols of Sixties' counterculture.

The Free Fairs inspired the Love Pageant Rally in October 1966, which itself

was the inspiration for the Human Be-In, in January 1967. The Be-In itself

became the model for similar gatherings worldwide; the most famous of which

occurred two years later in New York at a farm in upstate New York near

Woodstock.

Barbara Wohl, one of three people responsible for organizing the Free

Fairs, described the Artists Liberation Front as "an extension, for the most

part, of the very kind of loving tender attitude that people had toward each

other then. I haven't seen it since. It was just that short bubble of time.

If you weren't there, you don't even believe it happened ... I didn't

articulate it to myself at the time, but what the point of the fairs was,

was not to have artists displaying their works, finished products, but to

have the supplies there so people could make their own art. ... That was the

basic idea of the fairs. It is not someone coming to observe his picture,

but where whoever happened to walk up and see the paints could become the

artist and do his thing, make his own art, be a participant. This was meant

to be, and is, a very political thing. It was the beginning of this

burgeoning toward not passively allowing the government to go on with the

war. ... This erasing of the difference between the performer and the

performed upon was the real nitty gritty of that, the politics of the whole

thing."

See also:

|

|

|

In early Fall, 1966, two members of the Mime Troupe began mimeographing

and distributing street sheets with messages for the new community that was

coalescing in the Haight-Ashbury (months before any national attention hit

America's newsstands). At the suggestion of a member of SDS, they adopted

the name DIGGERS after the 17th century English radicals who had protested

the early stirrings of capitalism in the form of the enclosure movement by

moving onto the nearby commons and planting their crops to be shared freely

with all, abolishing money along with all buying and selling as part of

their living utopia. Gerrard Winstanley, one of the 17th century English

Diggers, had written the group's manifestos which outlined their beliefs and

principles: "This work to make the Earth a Common Treasury, was shewed us by

Voice in Trance, and out of Trance, which words were these, Work together,

Eat Bread together, Declare this all abroad. … Know this, that we must

neither buy nor sell; Money must not any longer (after our work of the

Earth's community is advanced) be the great god, that hedges in some, and

hedges out others."

These early street sheets, which were instantly dubbed “Digger Papers” in

the underground press, called for a renewal of purpose. As an anonymous

Digger told the Berkeley Barb, the message was aimed at "showing the gap

between psychedelica and radical political thought." The Diggers had

objected when the Artists Liberation Front debated allowing booths to sell

food and other goods at the Free Fairs and ultimately all buying and selling

was banned from these proto tribal gatherings. The early Digger Papers carry

some of the themes that would become synonymous with the Digger message:

rejecting Establishment norms; questioning all forms of authority and

conformity; and a challenge to create new spheres of autonomy (personal and

communal). In addition to these early broadsides, there are several notices

and articles that appeared in the Berkeley Barb which document these nascent

days.

See also:

|

|

|

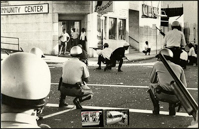

On Tuesday, September 27, 1966, a white policeman killed a Black teenager

in the Hunter's Point neighborhood of San Francisco. Matthew "Peanut"

Johnson was shot in the back after the officer suspected the car he was

driving had been stolen. Within a few hours, crowds of young men gathered in

the late afternoon and began confronting the police who were dressed in riot

helmets and shotguns on the streets of the predominantly Black neighborhood.

All night long, the crowds and the police were in pitched battles that

involved throwing of bricks and Molotov cocktails, breaking of windows,

setting of fires, and looting of stores. The police response was massive

cordons of officers firing into the crowds. Dozens of arrests took place.

The street confrontations between citizens and police spread into the

Fillmore district across town, and Mayor Shelley ordered a curfew until 6

a.m. The next day, Governor Edmund Brown ordered the National Guard to

patrol the streets of three of San Francisco's neighborhoods. The

Haight-Ashbury, being conterminous with the Fillmore district, was included

in the occupation order. Five hundred National Guardsmen patrolled the

streets of the City for six days until the emergency abated. During this

week, residents of the Haight-Ashbury differed in their responses. The

merchants urged cooperation with the police. Students for a Democratic

Society urged confrontation. The Diggers advised people to ignore the curfew

and passed the word that free food would be served to all comers in the

Panhandle, a sliver of Golden Gate Park adjacent to the Haight-Ashbury.

See also:

|

|

|

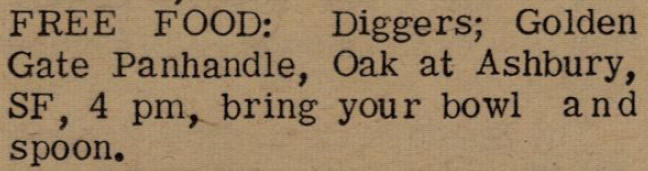

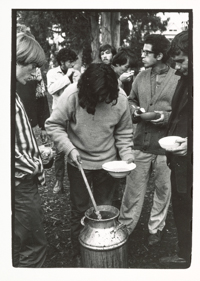

The act of offering free food in the form of Digger stew every day at 4pm

in Haight-Ashbury's version of the "English commons" was an electrifying

event in late September/early October 1966. Quickly, the movement

snowballed. As one of the later Digger Papers put it:

And so, six months ago you watched two guys bring a milk can full of

turkey stew into the panhandle and start the diggers. two weeks later

free food in the panhandle at four o'clock was advertised in the

berkeley barb and it never missed a day. somebody asked: Why free food?

and anyone answered: free clothes. the first free store opened in a six

car garage on page street and it was small and the crowd knew each other

and someone had written winstanley on the door and then the rains came

and the roof fell in, the landlord was harassed by the police and said

please … and someone said it was nice while it lasted. And the diggers

grew.

The Panhandle is a strip eight blocks long by one block wide filled with

lush lawns, towering eucalyptus trees, open playgrounds and walking paths

that forms the northern border of the Haight-Ashbury neighborhood. As soon

as the Diggers started serving free meals daily at the corner of Oak and

Ashbury in the fall of 1966, the Panhandle became the new community's

gathering place similar to the central plaza of a Spanish pueblo or the

Boston Commons during the American pre-revolutionary era. In the coming

months, the Diggers would bring flatbed trucks to the Panhandle and set up

the first outdoor music featuring the Grateful Dead and other local

bands. Candle-lit poetry readings would take place protesting the war in

Vietnam with a dual sense of the anger many young people felt but also the

joy that this new counterculture embodied.

See also:

The weekly ad that appeared in the Berkeley Barb's "Scenedrome" events

listings (origin of the phrase "bring your bowl and spoon"):

[Berkeley Barb, Nov 4, 1966, p. 12]

|

|

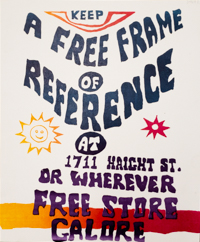

Free Stores: It's Free Because It's Yours

Within weeks of the first Free Feeds in the Panhandle, the Diggers had

rented a six-car garage a block away on Page Street. The garage contained

dozens of picture frames which inspired the Diggers to construct a

twelve-foot square frame of loose 2x4s. Painted bright orange, it became the

first prop the Diggers used in their street theater agit-prop — all comers

at the Free Feeds had to step through the "Free Frame of Reference" in order

to partake of that day's stew. The name also stuck for the garage after the

Diggers turned it into the first Free Store where all items were free for

the taking. No buying, no selling.

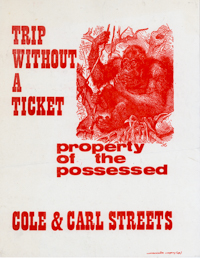

After the City closed the Free Frame of Reference free store, the Diggers

opened two more in the next year. The longest lasting incarnation was known

as Trip Without A Ticket, located at Cole and Carl streets in the upper

Haight. This was where street survival classes took place for new arrivals

in the youth mecca. This was where the first free medical services were

offered by local doctors and nurses who became enamored with the Digger

ideal. This was where the first tie-dye lessons took place which transformed

clothing styles for a generation. By the time this third Free Store closed

its doors, dozens of communes had sprung up in the Bay Area, many which

replicated the Free Store concept with a communal room of their own open to

anyone passing through. Decades later, Free Boxes outside natural foods and

other stores continued to proliferate in counterculture niches from Santa

Cruz, California to Burlington, Vermont. Full blown Free Stores continue to

operate in the 2020s, especially in low-income areas across the country.

One of the best-known free stores was the Black People's Free Store that

was started by Roy Ballard, a long-time Black civil rights activist in the

Fillmore district. Roy collaborated with the Diggers in the early months of

1967 and opened the Free Store in June. It was an immediate success and

continued for several years, eventually becoming host to a medical clinic

and community center. Roy's vision of the role of free stores as reparations

for the legacy of slavery is still an acute indictment of American society.

See also:

|

|

|

One of the early Digger Papers states, "The relationship between poetry

and revolution has lost its ambiguity. Gregory Corso's poem POWER was the

sole reason behind the concept of the Diggers: autonomy. The issue is no

longer the status of an American minority, but the status of America. The

Diggers are a rebellion against commodities and the hierarchy of commodity

values. … Create alternatives. Turn people onto their own creative powers.

The public is any fool on the street and power is standing on a street

corner waiting for no one." When someone asked who was in charge of the Free

Store, they would be answered, "You're in charge! You wanna see someone in

charge? You be in charge!" This was an example of the Digger "concept of

assuming freedom." It extended to the planning of public events that the

Diggers performed over the course of their two years on the stage of public

awareness. Starting with The Intersection Game on Halloween, October 31,

1966 — barely a month since the first Free Feed — the working model for a

Digger event was: "Life acts! Acts that can create the condition of life

they describe!" The condition the Diggers were describing first and foremost

was AUTONOMY. Later Anarchist theory would give a fancy name to this Digger

idea — prefigurative politics, meaning that a group replicates the ultimate

social ends they seek in their everyday practice. If you believe ultimately

in a non-hierarchical society (as anarchists do), then you structure your

current practice to reflect that in present relations.

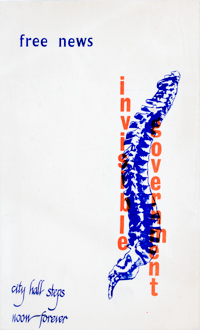

Cycle of Digger events (1966-1968):

- The Intersection Game (Oct 31, 1966)

- Death of Money Parade (Dec 17, 1966)

- New Year's Wail (Jan 1, 1967)

- The Invisible Circus (Feb 24-26, 1967)

- Gentleness in the Pursuit of Extremity (Apr 2, 1967)

- Dance of the Sorcerer's Apprentices (Apr 9, 1967)

- Candle Opera in the Panhandle (Apr 14, 1967)

- Summer of Love Solstice (June 21, 1967) [1st time]

- Death of Hip / Birth of Free (Oct 6, 1967)

- End of the War (Nov 5, 1967)

- Spring Equinox 1968 (Mar 20, 1968)

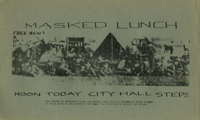

- Noon Poetry Forever (Spring 1968, City Hall steps)

- Free City Convention (May 1, 1968)

- Poetry Bust (May 7, 1968) [see

NOWSREAL]

- Masked Lunch (May 8, 1968)

- Summer Solstice 1968 (June 21, 1968)

See also:

|

|

|

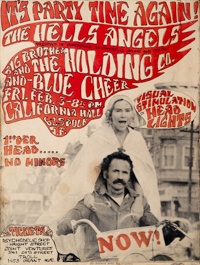

At the Death of Money Parade in December 1966, two Hells Angels happened

upon the street event and joined in. After one of the Diggers rode on the

back of an Angel motorcycle and stood waving a sign with the word "NOW" down

Haight Street, the police arrested her and the two Hells Angels. The Diggers

organized a march to the local police station where they proceeded to raise

bail money. In appreciation, the San Francisco chapter of the Hells Angels

decided to throw a party for the Diggers. The event was called "New Year's

Wail" and it took place on January 1, 1967, in the Panhandle. From that

moment on, there was a close relationship between the two groups. At the

event, two recent arrivals on the scene took notice of the Digger ethos and

became inspired to launch an instant news service for the Haight-Ashbury.

They called it the Communication Company.

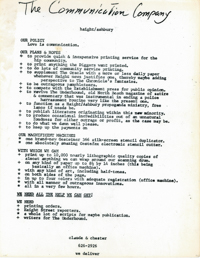

The collective members (there were a total of five) of the Communication

Company fashioned themselves the publishing arm of the Diggers. As such,

their record of broadsides, manifestos, leaflets, and street sheets leaves

us a rich slice of Digger praxis as it played out on the streets of the

Haight-Ashbury during the spring and summer months of 1967. Many of the 700+

anonymous sheets came from the Diggers themselves; others had been penned by

the elder statesman of the Communication Company collective, himself a Beat

Movement survivor from North Beach and Greenwich Village who gravitated to

the new scene in the Haight. Inspired by the Diggers and their Free

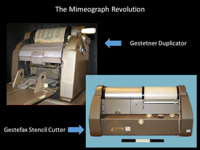

philosophy, the Communication Company set up a printing operation with two

Gestetner mimeograph machines that had been nefariously obtained through the

offices of Ramparts magazine. Everything (or nearly so) was free of charge.

If someone heard a rumor of a bust, or had a good lead on free food, or

wanted to announce a poetry reading, the Communication Company had roving

reporters on the street who could rush at a moment's notice back to the flat

where the Gestetners were kept. Within a short time, a new street sheet

would appear, distributed by the volunteers who used the street poles as

their community bulletin board.

See also:

|

|

Free Bakeries, Free Clinics: The Movement Expands

The thing about social movements is that they can take on the

characteristic of an avalanche that starts with a snowball cascading down

and picking up energy and mass from its gravity. That's what happened with

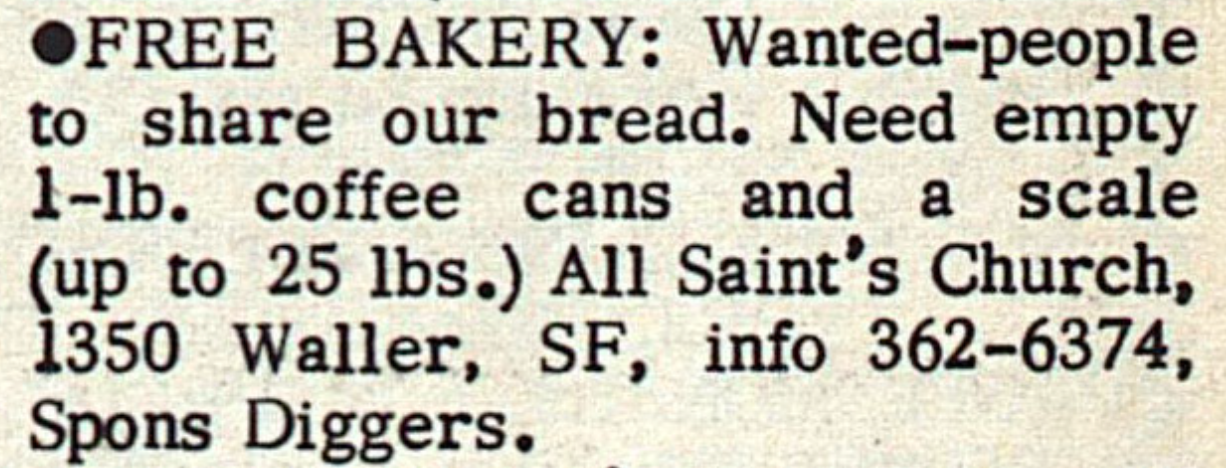

the Digger Movement. One Saturday in June 1967, an engineer and his wife

from Palo Alto brought 400 lbs. of whole wheat flour to the All Saints

Church on Waller Street. The prelate of the church had become inspired by

the Digger idea and gave over his office to a group of "street Diggers" who

set themselves up as one wing of the growing movement. Installed in the

kitchen of the church were two large ovens. The Palo Alto couple offered to

teach the Diggers how to bake whole wheat bread. There were no baking trays

so they innovated by using one- and two-pound coffee cans which became the

trademark identity of Digger Bread. The bread makers were adamant about

using ONLY whole wheat flour for the baking, and their passion for whole

grains quickly found a receptive audience throughout the Haight and the

larger counterculture (as evidenced by articles in underground newspapers of

the time). Free bakeries sprung up during the coming years and decades

wherever young people gathered. One of the most renowned was the God's Eye

Bakery at Resurrection City in 1968 at Martin Luther King Jr.’s last

crusade, the Poor People's Campaign in Washington, D.C.

Meanwhile, at the Trip Without A Ticket free store in the Upper Haight, a

group of interns and doctors had come together to volunteer their services

for the young people who were gravitating to the Haight. From this nexus

emerged the Haight-Ashbury Free Medical Clinic founded by a doctor on staff

at the University of California San Francisco medical school. The Free

Clinic became an instant success and longstanding institution. As the

director of the Free Clinic noted, in the Digger world, "Health care is a

right not a privilege" and that has become the working motto of Free Clinics

since then.

See also:

|

|

|

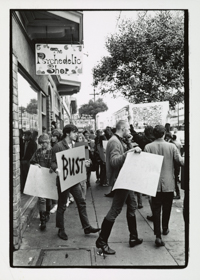

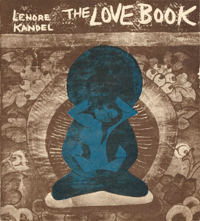

Backing up a bit in terms of chronology, on Tuesday, November 15, 1966,

San Francisco Police officers working the Vice Squad arrested the store

clerk at the Psychedelic Shop on Haight Street for selling copies of a book

of poetry by Lenore Kandel, a longtime member of North Beach bohemian

society. The title of the poems was The Love Book and this event became

known as The Love Book Bust. Subsequently, the police arrested the owner of

the Psychedelic Shop as well as a store clerk at City Lights Bookstore on

the grounds that The Love Book was obscene. The case became the longest

running criminal trial in San Francisco history to that point. The new

community that had migrated to the Haight-Ashbury was outraged by the

ongoing harassment of the police and City Hall who, it seemed obvious, were

determined to rid San Francisco of this fringe subculture before things

really got out of hand. By this moment in late 1966, LSD usage had become

common among the "new bohemians" (as some would continue to call them — the

term "hippies" had only recently been used). Members of the new community

called for a meeting to band together to resist this onslaught by the

Establishment. The result was a meeting that included some of the new "hip"

merchants, artists, publishers, writers, and representatives of collective

groups — including the Diggers — and some of the neighborhood rock groups

like the Family Dog and the Grateful Dead. Using the eponymous title of

Lenore Kandel's poetry book, this group of new leaders proclaimed the coming

season to be the "Summer of Love" and set about inviting the world to their

doorstep.

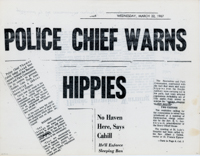

As soon as some of the members of the "Council for a Summer of Love"

began predicting the imminent arrival of thousands of young people to the

Haight-Ashbury, the Mayor and City Hall reacted in horror. The headline

read: "Hippies Warn S.F. / Huge Invasion" in the March 22, 1967, S.F.

Chronicle. A later edition changed the headline to read: "Police Chief Warns

Hippies" and that began a sustained assault by the police and bureaucrats

that continued daily and weekly throughout the summer, into the fall and

winter and even into the next year until finally the Haight imploded on

itself and became a burned-out shell of its former self. Nevertheless, the

Summer of Love was a time of opening — opening of alternatives such as the

Free Bakery, the Free Clinic, the Switchboard, Digger crashpads, street

takeovers, weekly free music gatherings in the Panhandle. All the while,

Free Food and the Free Store continued serving up “Digger Do” as the Diggers

called their action-oriented ideology. Eventually, the combined pressure of

the thousands of young people who made the pilgrimage to the Haight-Ashbury

that Summer of Love — and at the same time, the relentless arrests and

harassment of the Establishment — forced a retreat. Just as the Diggers had

jumped off the stage of the Mime Troupe onto the streets to carry out their

agit-prop theater, now there was a pulling inwards. Hundreds of communes

formed in the ensuing months and the action went indoors.

See also:

- "Love is a Four-Letter Word" (history of the Love Book Bust

and Trial)

|

|

Free City: Blueprint for Collectivity

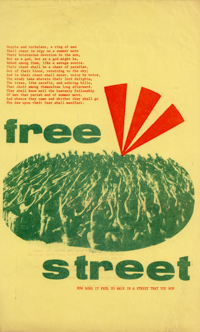

In the summer of 1967, the Diggers gave away their last, final,

possession — their name. Henceforth, they called themselves Free City. One

of the last events that the Diggers (under that name) created was the Death

Of Hippie in October 1967, in an attempt to discard a word that had been

invented by the mass media. The full name of the event was “Death of Hippie

and Birth of Free.” The name "diggers" had become so widely used that it was

like a ripple wave in a pond. People called themselves Diggers all over the

map of the now widespread counterculture, in the same way that the Berkeley

Provos had adopted the name of the Dutch anarchist group the previous fall.

The Digger vision, which had loosely been "Free Street" now expands into

the vision of Free City, which included not just the Haight-Ashbury but many

other of San Francisco's unique neighborhoods: the Mission, Fillmore,

Chinatown, Castro, Potrero Hill, Noe Valley. The Free City Collective, ever

life-actors looking to expand their performance art, brought their events to

the stage of the larger urban context — the Free City Convention; the Free

Poetry Readings on City Hall Steps; the Spring Equinox and Summer Solstice

celebrations. These were the cycle of events that the Free City Collective

created in 1968 to put forth a more inclusive, communal energy. Free Feeds

in the Panhandle morphed into the "Free Food Home Delivery" service that

brought scrounged fruits and vegetables from the Produce Market to the

communes and households that formed the Free City network. One of the groups

that ended up on the delivery route was the headquarters of the Black

Panthers in Oakland. David Hilliard, the chief of staff of the Panthers,

describes in his autobiography how the Diggers inspired the Panthers’ Free

Food and Breakfast for Children programs. The Free Food Home Delivery

Service in turn inspired the formation of the first Food Conspiracy in the

Bay Area which was a key moment in the genesis of the natural foods

movement.

In late summer, 1967, some of the Diggers forcibly appropriated the

Gestetner equipment that had been used to produce the Communication Company

(Com/Co) bulletins. The Free City Collective used these machines to create

the Free City News sheets, which supplanted the Com/Co operations. The

hard-edge editorials and the black and white productions typical of Com/Co

were replaced by a larger (8-1/2" x 14") format, colorful designs, and more

poetic pronouncements. The final publication of the Free City Collective was

the August 1968 issue of The Realist for which the Diggers were given 40,000

copies of a Free edition titled “The Digger Papers” —an anthology of

manifestos, street sheets and Free News items that had appeared in the

previous eighteen months. Many saw this compilation as the final gift from

an amazing collection of individuals and the blueprint for a future

collectivity.

See also:

|

|

|

Hundreds of communes in the San Francisco Bay Area sprang up starting in

1967. One among them, the Sutter Street Commune, consciously adopted the

Digger Free philosophy. The Digger ethos had permeated the counterculture

—communes invariably had a Free Box in the hallway, whole wheat bread in the

communal kitchens, and tie-dyed shirts in the communal clothes rooms — but

the Sutter Street Commune was dedicated to implementing the collective

blueprint for action that had appeared in “The Digger Papers.”

Since the 1950s, tales of Buddhist enlightenment had permeated the

counterculture with the Beat poets' interest in Zen. One of the concepts

that gained popular renown was the idea of "passing of the dharma." This was

the idea of sacred teachings being passed from teacher to student. A passing

of the dharma between the Diggers and the Sutter Street Commune took place

in the early months of 1968 at one of the daily Free City Noon Forever

events at City Hall. The commune's founding member was convinced to bring

his printshop (offset press, copy camera, light table, etc.) from the Lower

East Side of Manhattan to San Francisco to start a free printing service.

Just as the Communication Company had been inspired by the Diggers and set

up their instant news service during the Summer of Love, so the Sutter

Street Commune announced the opening of the Free Print Shop in August 1968.

Over the next decade and beyond, they would provide free printing of all

manner of publications for communes and collectives that were themselves

providing free services to the community. The Free Print Shop collection

contains a record of hundreds of such items, distinctive for their artistry

and design.

See also:

|

|

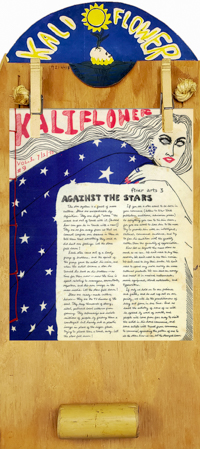

Kaliflower: Intercommunal Explosion

In the spring of 1969, the Sutter Street Commune, under the auspices of

the Free Print Shop, began publishing a newspaper that was only distributed

by hand to communes. The name they gave this free weekly publication was

Kaliflower, a play on Kaliyuga, the Hindu name for the last and most violent

Age of Humankind — the idea being a "flower growing out of the ashes of this

current age of destruction." For the next four years, the commune kept

Kaliflower going, 113 weekly issues in all. At its end, there were close to

three hundred communes receiving Kaliflower. The progeny became so well

known that eventually it gave its name to the parent — the "Kaliflower

Commune" was how many people knew the group that published the weekly

intercommunal newspaper.

"Kaliflower Day" — the name by which Thursdays became known — was an

intercommunal ritual. That was the day when Kaliflower got printed, hand

bound, and distributed to all the other communes on the "routing list."

Members from other households would show up at the Sutter Street Commune and

spend the morning hand binding the pages of the newspaper, using the

Japanese side-stitch method which members of the commune had learned from

their salvage stints in the old abandoned Victorian houses of San

Francisco's Japantown and Western Addition neighborhoods. After a deliverer

had bound enough copies for their route (typically a dozen communes each),

they would set out on the day’s journey. It was not unusual for the

Kaliflower deliverers to come back with stories from one commune to another

and being feted at each in various fashions. At each stop, the deliverers

would pick up announcements and ads (always Free Ads) that would appear in

the next week's issue. Kaliflower, in the printed form, but even more so in

its method of distribution, became a channel of communication among hundreds

of communes — thus fulfilling the Digger maxim ‘create the condition you

describe.’

Since the basis of the Sutter Street commune's vision was Digger Free,

Kaliflower also became the vehicle that helped create a Free City among the

hundreds of communes. Eventually, a core group of communes pooled all their

food-buying resources and operated on a “from each according to ability, to

each according to need” basis. Among the Free Food Family of communes were

the Angels of Light Free Theatre Troupe; Hunga Dunga which coordinated the

food buying and delivery; the Free Medical Opera which provided health care

services; Sutter Street which continued to operate the Free Print Shop and

produce Kaliflower; and many others.

See also:

|

|

|

In the decades after the 1960s, the ideas of the Digger Movement

continued to suffuse radical social movements. Evidence of this comes from

any issue of the hundreds of underground newspapers that proliferated in the

era. For example, the weekly "Scenedrome/Survival" section of the Berkeley

Barb would list dozens of services from free food, free bakeries, free

stores, free medical clinics, free lawyers, etc. A core group of the Diggers

left the urban concentration to join the "back to the land" movement in the

late 1960s and evolved a radical environmental approach they called

Bioregionalism. Meanwhile, as the 1980s progressed, AIDS took its toll on

the San Francisco gay counterculture including many of the same communes

that had comprised the Kaliflower network. The Anti-Nuclear and Central

American Solidarity movements took up where the Anti-Vietnam War movement

had left off after the end of the United States involvement in Vietnam in

1975. Aspects of the Digger ethos of autonomy were present in civil

disobedience direct actions, especially the new form of affinity groups as

the basis of collective non-hierarchical organizing. In 2011, at the lower

Manhattan location known as Zuccotti Park, an encampment of hundreds of

tents and thousands of participants formed the Occupy Wall Street movement.

As if drawn directly from the 1968 anthology of The Digger Papers, the

Occupy encampment included a free store, a free kitchen, free library, free

energy generation, as well all the tools of consensus decision-making that

the anti-nuclear movement had innovated. As Chris Carlsson, co-founder of

Shaping San Francisco, suggested, even though few of the Occupy activists

had heard of the Diggers, nevertheless, the Digger DNA had suffused radical

social movements in the subsequent decades. Traces of the Digger Movement

were now the roots of a new radical social movement.

See also:

|

|

Coda: Celebrate and Protect the Commons

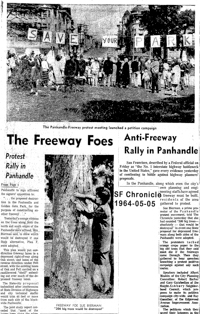

Consider the importance of the Panhandle to the rise of the

Haight-Ashbury. That eight-block long strip of green that defined the

boundary of the Haight-Ashbury was for the San Francisco Diggers what St.

George’s Hill was for the 17th Century English Diggers. It was the Commons,

the open space that all could enjoy no matter one’s status in life. As the

English Diggers moved onto St. George’s Hill at the moment when English

aristocracy was enclosing the Commons lands, so too the 20th Century Diggers

turned to the Panhandle at a moment when it had barely escaped a similar

fate. In March 1966, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors (the equivalent

of City Councils elsewhere) had finally defeated a plan to build an

eight-lane freeway through the Panhandle to connect with the Golden Gate

Bridge. The plan had been brewing for two decades and would have destroyed

this expanse of open space within a dense residential neighborhood. A

citizens’ group based in the Haight-Ashbury had formed and vociferously

opposed the Panhandle Freeway at every turn. Arrayed against big business,

big labor, and the state highway engineers, the dedicated group of

Haight-Ashbury citizens deserve — at the least — a plaque to commemorate

their steadfastness. If the Board of Supervisors had approved the freeway in

March 1966, the State would have fenced off the area, preventing the Digger

Free Feeds and all subsequent gatherings. The Panhandle was where the new

community first gathered in a free space, outside the confines of commercial

venues. The Panhandle shows how parks and open spaces became the catalyst

for the coming-together of numerous Sixties Counterculture outposts — the

Polo Fields in Golden Gate Park (Human Be-In, January 1967), Sheep Meadow in

Central Park (Easter Be-In, 1967), Tompkins Square Park (New York City’s

Lower East Side), Griffith Park in Los Angeles, Boston Commons, Berkeley’s

Provo Park and People’s Park, Max Yasgur’s Dairy Farm (Woodstock Music

Festival, 1969). The Free Commons is where Sixties Counterculture first came

together. Celebrate the Free Commons. But protect it like that group of

citizens who saved the Panhandle from enclosure in 1966.

|

|

|

|

|

- v.3 Distributed at the event "Our Commons are Free" in Santa Rosa, CA,

May 2022.

- v. 5 Distributed at the CABARE spectacle in Livorno, Italy, Sept 24, 2022

- v. 6 Web published Feb 2023

|

|

(DA) = Digger Archives collection

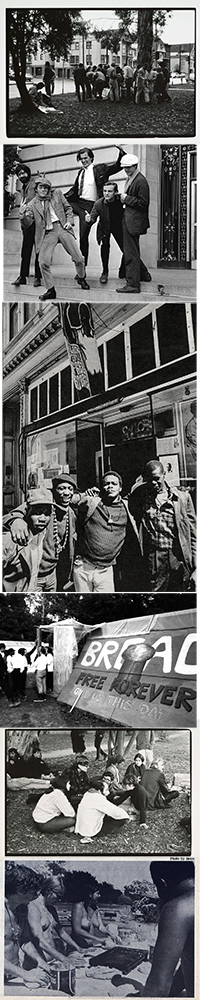

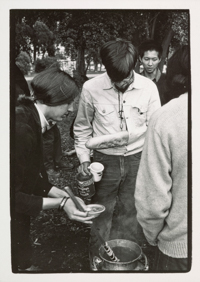

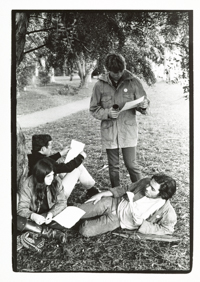

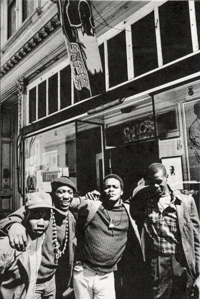

Introduction (photo collage). From top: (1) October 1966 Digger Feed in

the Panhandle (photo by William Gedney); (2) Front-page photo from the San

Francisco Chronicle (Nov 30 1966) of five Diggers in a famous pose outside

City Hall (photo by Bob Campbell); (3) Black People's Free Store (photo by

Bill Owens); (4) God's Eye Free Bakery at Resurrection City, Washington,

D.C., Poor People's Campaign, 1968 (photo unk.); (5) group attending a

Digger Free Feed in the Panhandle, October 1966 (photo by William Gedney);

(6) baking Digger bread at Olompali Commune, 1968 (photo by Reim).

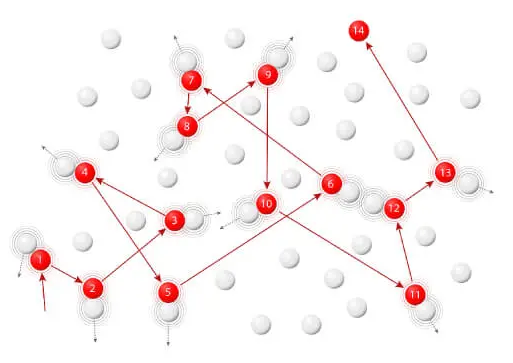

Epigraph: Radical Social Movements, Roots and Traces. Diagram of Brownian

motion showing random movement of particles.

SF Mime Troupe: Praxis of Change. From top: (1) Mime Troupe members at a

performance in the park (photo by Erik Weber); (2) poster for the Mime

Troupe show "The Miser."

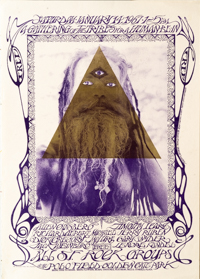

Artists Liberation Front: Celebration as Community. From top: (1) poster for

the Artists Liberation Front Free Fair at Glide Church, Oct 8-9, 1966 (DA);

(2) poster for the Human Be-In, Jan 14, 1967 (DA); (3) poster for the

Invisible Circus, Feb 24, 1967 (DA).

The Digger Papers: Counterpoint to Ecstasy. From top (l to r): Where is

PUBLIC at?; Cool Cranberry Horsehaired Mouth; Let Me Live in a World Pure;

And Now I Live And Now My Life Is Done; Public Nonsense Nuisance; Time To

Forget; Take a Cop to Dinner; A-Political Or, Criminal Or Victim Or.

Hunter's Point Uprising: Community Under Siege. From top: (1) Police

officers drawing their guns on residents during the 1966 Hunter's Point

uprising; (2) and (3) National Guard troops patrolling the streets during

the 1966 Hunter's Point uprising.

Free Food Daily: Bring Your Bowl and Spoon. Digger Feed in the Panhandle,

Oct 1966 (photos by William Gedney).

Free Stores: It's Free Because It's Yours. From top: (1) A Free Frame of

Reference poster printed by the Free Print Shop, ca. 1969 (DA); (2) Black

People's Free Store (photo by Bill Owens); (3) Trip Without A Ticket free

store flyer, printed by Communication Company, 1967 (DA).

Digger Event Cycle: Create the Condition You Describe. From top: (1) Hells

Angels party poster (showing Phyllis riding on the back of "Hairy Henry"

Kot's Harley during the Death of Money parade); (2) Death of Money parade

(photo by Gene Anthony); (3) Gentleness in the Pursuit of Extremity is No

Vice, printed by Communication Company, 1967 (DA); (4) Masked Lunch flyer,

May 8, 1968 (Free City broadside, DA); (5) The End of the War poster, Free

City, Nov 5, 1967 (DA).

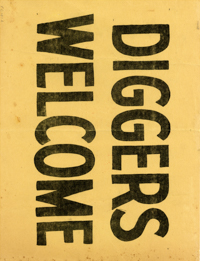

Communication Company: Instant News Service. From top: (1) The Communication

Company … Our Plans, printed by Communication Company, 1967 (DA); (2) The

Mimeograph Revolution (image of a Gestetner mimeograph machine and a

Gestefax stencil cutting machine); (3) Diggers Welcome, printed by

Communication Company (DA).

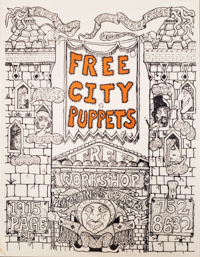

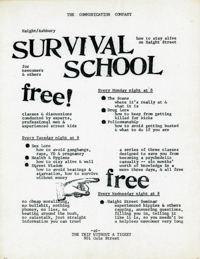

Free Bakeries, Free Clinics: The Movement Expands. From top: (1) Free Bakery

ad from the Berkeley Barb; (2) od's Eye Free Bakery at Resurrection City,

Washington, D.C., Poor People's Campaign, 1968 (photo unk.); (3) Free City

Puppets poster, printed by the Free Print Shop, 1971 (DA); (4) Survival

School, printed by the Communication Company, 1967 (DA).

The Summer of Love: News Gets Out. From top: (1) Psychedelic Shop bust of

the Love Book, Nov 15 1966 (photo by William Gedney); (2) Cover of The Love

Book by Lenore Kandel (DA); "On the 3rd anniversary …" (broadside

distributed at the Psychedelic Shop on Nov 22 1966) (DA).

Free City: Blueprint for Collectivity. All four items printed by Free City,

1967-1968. (DA).

Free Print Shop: Passing of the Dharma. From top: (1) Kaliflower Commune in

the backyard of the Scott Street house, 1972. (Photo by Miriam Bobkoff);

announcement of the opening of the Free Print Shop, August 1968 (DA).

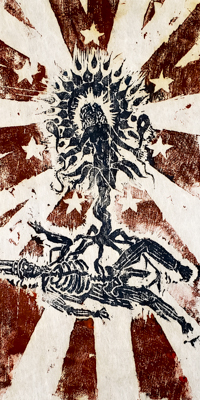

Kaliflower: Intercommunal Explosion. From top: (1) a Kaliflower Board with a

copy of Kaliflower, vol 3, no. 9 (July 1, 1971) affixed (DA); (2) woodblock

print of Kaliflower springing from the corpse of Uncle Sam (DA); (3) Allen

Ginsberg playing harmonium at the Angels of Light performance (photo by

Jerry Walker, original in the Irving Rosenthal Papers at Stanford

University).

Decades On: Digger Resonance. Occupy Wall Street at Zucotti Park, Manhattan,

NYC, Oct 30, 2011 (photos by Eric Noble).

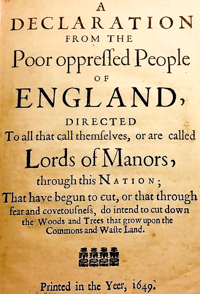

Coda: Celebrate and Protect the Commons. From top: (1) Cover page for the

1649 English Digger manifesto "A Declaration from the Poor oppressed People

of England…" (photo by Eric Noble); (2) newspaper article about a large

anti-Panhandle Freeway protest, May 5, 1965; (3) photo of the Panhandle

leading to Golden Gate Park in the distance (photo by Steve Proehl). |

|

| |

|

| |

|

![High-Res Image]()

|